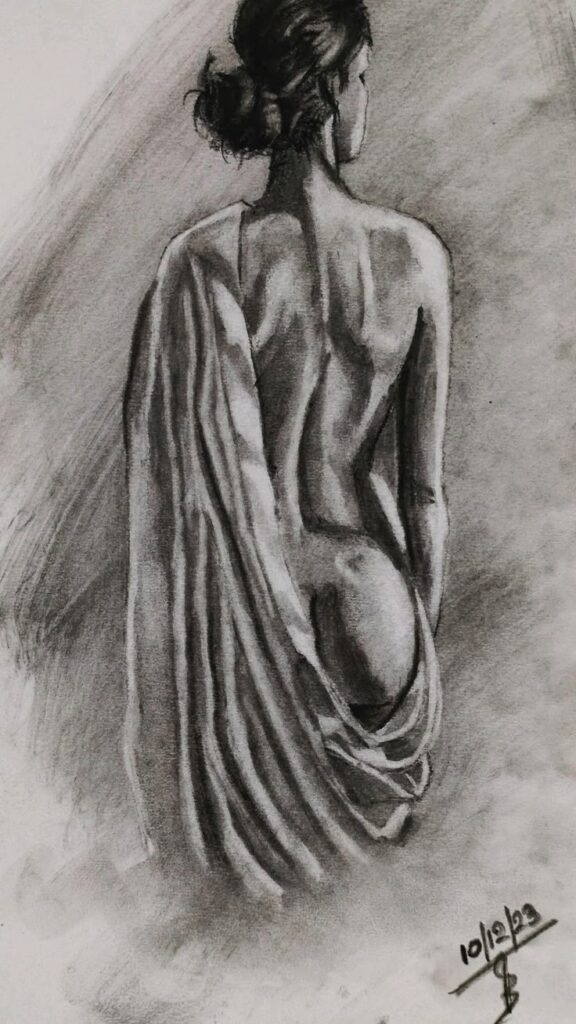

You’ll learn how charcoal helps you study the human form with fast marks, rich shadows, and a direct connection to gesture and anatomy. Charcoal lets you capture movement, volume, and light quickly so that you can build strong, expressive Charcoal Human Figure Sketches even with simple tools.

This post shows what materials to choose, core techniques to try, how to read light and composition, and ways to make the figure feel alive on the page. Expect clear steps for practice and ideas to spark your own style so your sketchbook fills with confident, honest work.

What Is Charcoal Nude Figure Drawing?

Charcoal nude figure drawing shows the human body using charcoal sticks, pencils, or vine charcoal on paper. It focuses on shape, light, and posture so you can study anatomy, gesture, and value with a direct, expressive tool.

Basics of Charcoal as a Medium

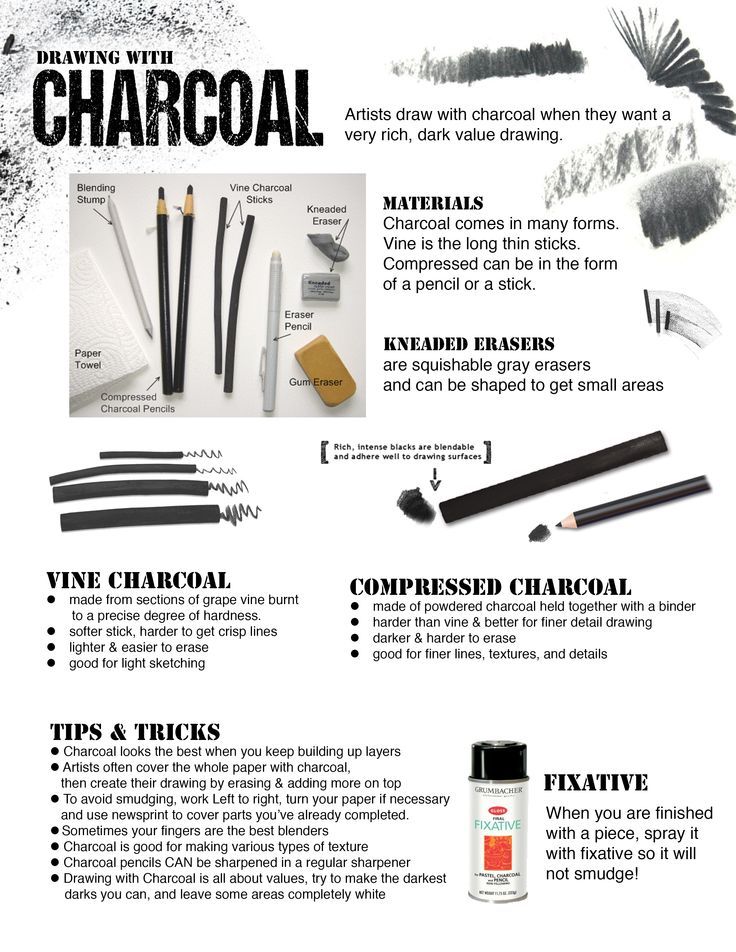

Charcoal comes in several forms: vine (soft, powdery), compressed (darker, denser), and charcoal pencils (more controlled). Vine charcoal erases easily and gives soft edges for quick sketches. Compressed charcoal holds dark tones well for strong contrasts and finished pieces.

You work on toned or white paper and often use a kneaded eraser to lift highlights. Smudging with a finger or stump blends values smoothly. Expect dust and bold marks — charcoal reacts quickly to pressure and angle, so practice controlling line weight.

Tools to keep nearby:

- Vine and compressed charcoal

- Charcoal pencils for detail

- Kneaded and rubber erasers

- Blending stumps or chamois

- Toned paper (grey or tan) for mid-values

Defining Figure Drawing

Figure drawing records the human body from observation or reference. You study proportion, gesture (the overall movement), structure, and how light shapes form. Work ranges from short gesture studies (30 seconds–5 minutes) to longer, measured sessions that capture anatomy and shading.

You aim to translate three-dimensional forms into value and line. Start with simple landmarks: head, ribcage, pelvis, and major joints. Build volume with basic shapes before adding muscles and subtle planes. Practice measuring with sighting techniques to keep proportions accurate.

Typical session types:

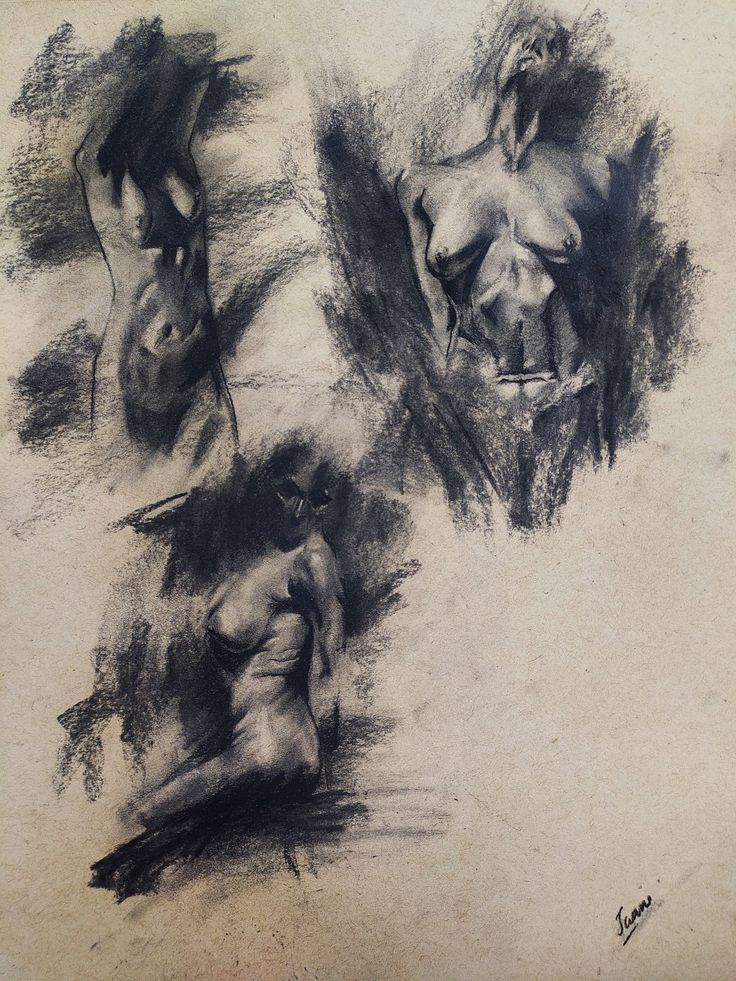

- Gesture: quick poses for rhythm and flow

- Short studies: 10–30 minutes for blocking and value

- Long studies: 1 hour+ for detailed anatomy and finish

Advantages of Charcoal for Nudes

Charcoal reacts well to the human form because it easily renders both soft transitions and bold contrasts. You can capture skin planes, deep shadows, and delicate highlights without complex tools. The medium’s range lets you move from light sketching to rich, dark blacks in one drawing.

Erasing is part of the process, so you can refine highlights and correct mistakes quickly. Blending creates smooth tonal gradations that mimic flesh. Charcoal’s speed supports live-model sessions where poses change, helping you record gesture and mood before the light or model shifts.

Essential Materials for Charcoal Nude Figure Drawing

You need a few focused supplies to start drawing the nude figure: charcoal types for different marks, papers that hold value and texture, and tools for blending, fixing, and correcting. These items affect line quality, shading, and how long your drawing lasts.

Types of Charcoal

Choose vine (stick) charcoal for light, sketchy lines, and soft shading. It erases easily and gives a dusty look that’s great for quick gesture studies. Willow or compressed vine works well for warmups and fast mark-making.

Use compressed charcoal when you want darker, richer blacks and stronger edges. It holds a point and makes bold contours and deep shadows. Compressed sticks come in hard, medium, and soft—pick medium for versatility.

Charcoal pencils give control for small details like facial features and fingernails. They come in varying degrees of hardness. Keep a range: soft for darks, hard for lines. A battery-powered blender or charcoal stick sharpeners help maintain points.

Recommended Papers

Pick an acid-free paper with tooth (tooth = surface texture). Papers labeled “charcoal” or “mixed media” usually work best because they grab charcoal and let you layer values.

Weight matters: 90–200 lb (190–300 gsm) sheets resist warping when you erase or use fixative. Larger sizes, like 18 x 24 inches, suit full-figure studies; smaller pads work for quick poses.

Color choices affect tone. Mid-tone gray or buff papers give instant mid-values, making it easier to build lights and darks. Keep a pad of smooth paper for fine detail and a rougher sheet for expressive textures.

Supporting Tools

Carry a kneaded eraser for lifting charcoal and creating soft highlights. It molds to small shapes so you can pull precise highlights in hair or collarbones. Use a vinyl eraser for stronger, cleaner erasures.

Blend with tortillons, stumps, or soft brushes—each gives different textures. Tortillons smooth small areas; brushes spread charcoal subtly for skin tones. Avoid over-blending; preserve some grain for structure.

Other essentials: a fixative spray to protect finished drawings, masking tape to hold paper down, a mahlstick or backboard for stability, and a cloth or smock to keep charcoal off clothes. Keep a small spray bottle of water if you use charcoal washes.

Fundamental Techniques in Charcoal Nude Figure Drawing

You’ll learn how to use line to find gesture, how to model form with tones and smudging, and how to measure key landmarks to keep proportions accurate.

Line Quality and Gestures

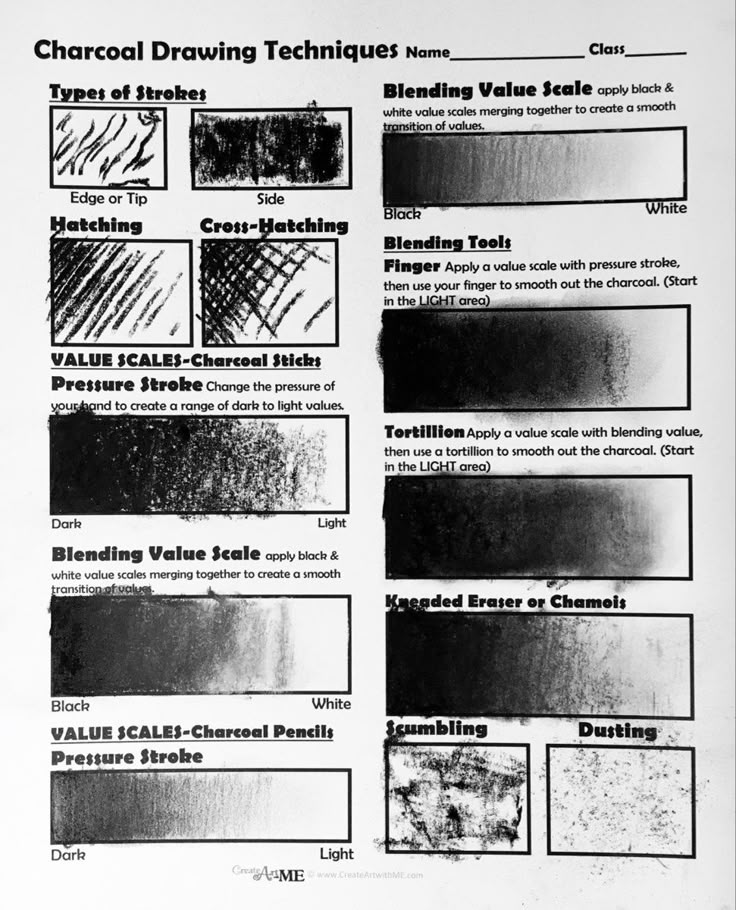

Start with quick, loose marks to capture the pose’s action and flow. Use a willow or vine charcoal for light, fluid lines and a compressed stick for darker accents. Focus on the spine line, shoulder tilt, and hip axis first; these three lines lock in the figure’s overall rhythm.

Vary pressure and stroke speed to show weight and movement. Light, continuous strokes suggest stretch or extension. Shorter, heavier strokes show weight-bearing parts like the foot or elbow.

Keep erasers handy to lift charcoal and create highlights. Use a kneaded eraser to gently pull tone and refine contours without making hard edges.

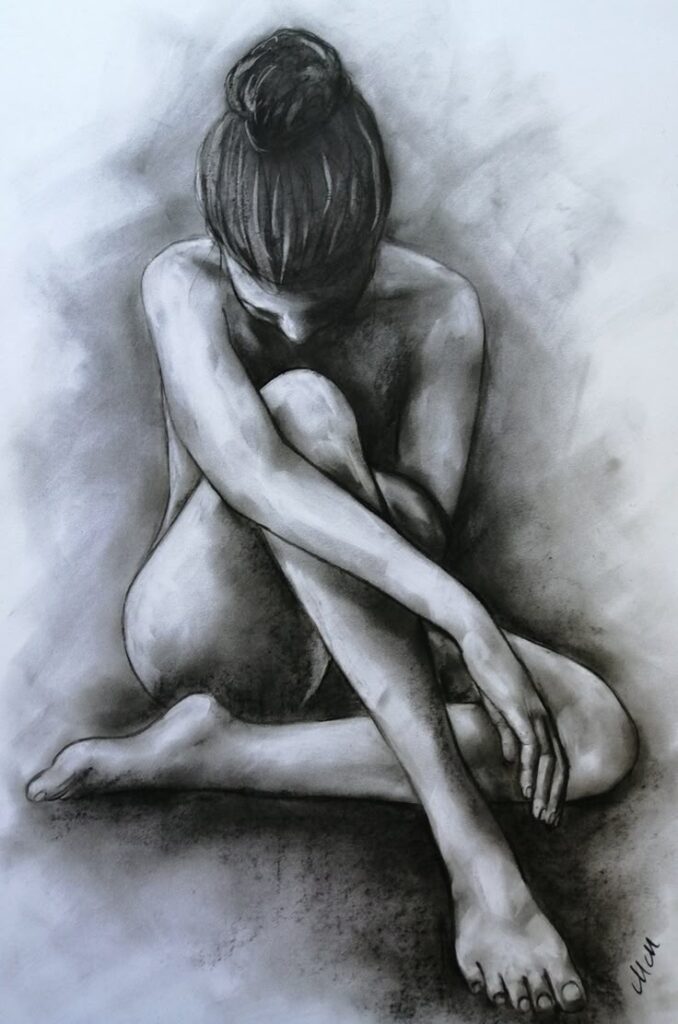

Shading and Blending Methods

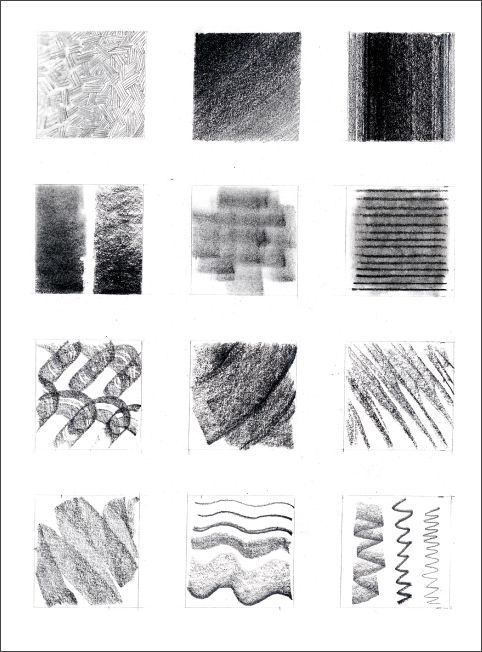

Block in large planes of light and shadow before adding detail. Use the side of the charcoal for broad value areas and the tip for edges and small shadows. Work from midtones toward darks; reserve the white of the paper for the brightest highlights.

Blend with a paper stump or your fingertip to smooth transitions, but keep some textured strokes to suggest skin and muscle. Cross-hatching adds subtle texture and control when you need clearer edge definition.

Use an eraser to cut crisp highlights and to correct values. Step back often to check overall contrast and to keep the figure readable from a distance.

Capturing Proportions

Measure with a sighting tool or a simple pencil to compare head lengths and limb ratios. Start by marking the head height; most adult figures are about 7–8 heads tall. Check the distance from the chin to the nipple, the nipple to the navel, and the navel to the groin to spot common proportional errors.

Place landmarks: ear level for the shoulder line, wrist at upper thigh when arms hang, and knee placement at roughly halfway down the leg. Adjust for foreshortening by comparing angles and overlapping forms, not by relying on assumed lengths.

Constantly compare parts to the whole. If a limb reads too long or short, erase selectively and redraw only the problematic segment to keep the rest intact.

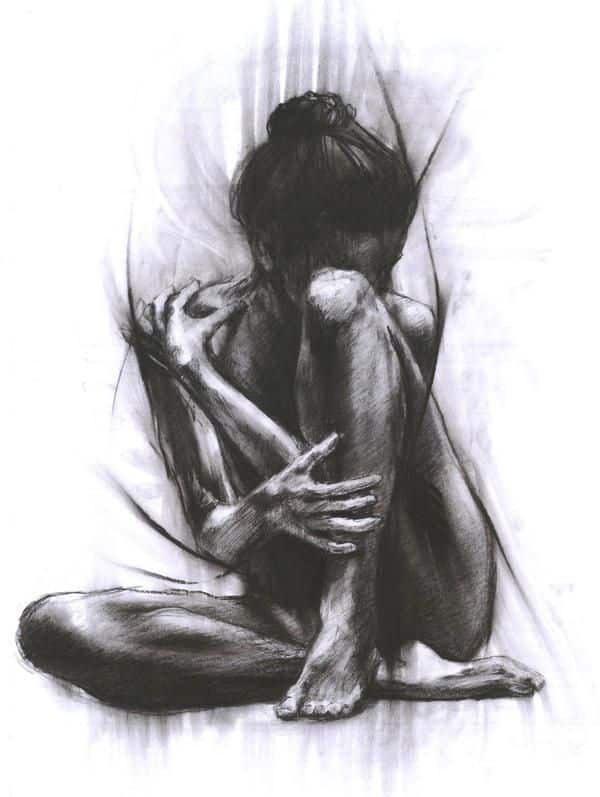

Approaching the Human Form

Focus on simple shapes, clear landmarks, and the flow of the pose. Start by mapping bones and masses, then refine with gestures, planes, and value.

Establishing Structure

Begin with a light, loose gesture to capture the pose’s main line. Use a single sweeping line for the spine and quick marks for the head, ribcage, and pelvis. These marks set proportion and tilt before you add detail.

Block the body into basic volumes: ovals for the ribcage and pelvis, cylinders for limbs. Measure relationships—head lengths, shoulder-to-hip width, limb ratios—so you can adjust while drawing. Erase confidently; charcoal allows you to rework shapes.

Place key landmarks: clavicles, iliac crests, knees, and elbows. Mark them faintly so they guide contour and shadow. Work from general to specific: solid structure first, then contours and subtle shapes.

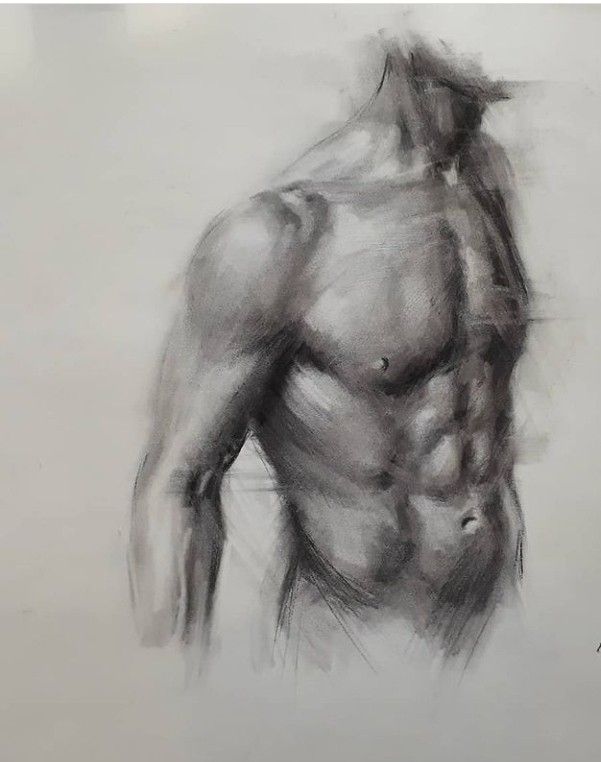

Understanding Anatomy

Learn the major bones and muscle groups that show through form: skull, ribcage, pelvis, femur, humerus, and key muscles like the deltoid and quadriceps. You don’t need full medical detail—know how these parts change the surface planes.

Study how anatomy affects silhouette and shadow. For example, the scapula shifts the shoulder plane when the arm lifts, and the pelvis tilt changes waistline angles. Note where skin stretches over bone and where fat softens an edge.

Use quick anatomical sketches from reference to train your eye. Mark where tendons and muscle striations alter light. Keep notes near your drawing to remind yourself of recurring structures.

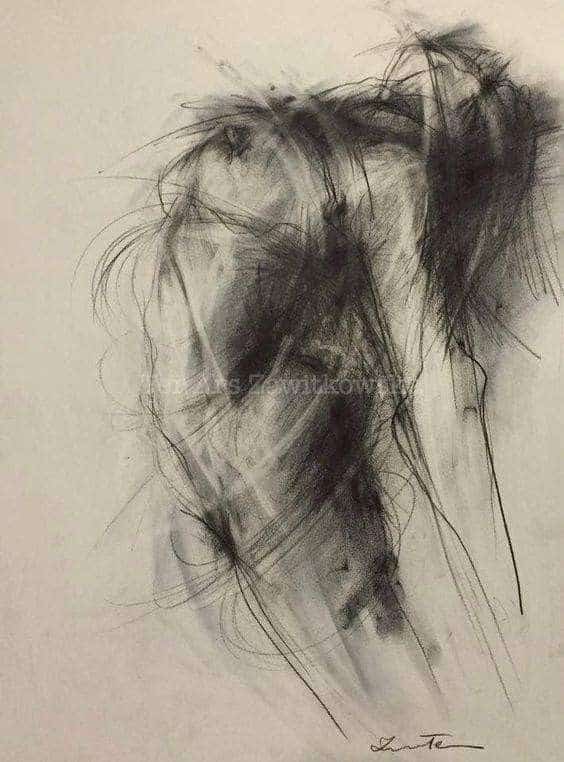

Expressing Movement

Capture movement through rhythm and weight. Begin with a gesture that shows force direction—where the weight rests and which limb pushes or pulls. The gesture should feel alive, not stiff.

Emphasize the line of action and counterbalance. Show how the head and pelvis oppose each other when the body twists. Use overlaps and foreshortening to imply depth and motion.

Use charcoal’s range: soft smudges for blurred motion, sharp lines for tense edges. Vary mark speed—quick strokes for energy, slow strokes for weight. This contrast brings the figure to life.

Lighting and Composition for Dynamic Drawings

Focus on clear light direction, strong value contrasts, and a simple layout that guides the eye. Place the figure off-center, control contrast to show form, and use negative space to balance the pose.

Using Light and Shadow

Choose one main light source to keep shadows readable. Strong side or three-quarter lighting reveals planes and muscle groups. Use hard edges for cast shadows and soft edges for form shadow to show depth.

Block in large value shapes first: light, midtone, and shadow. Work from general to specific — refine highlights and reflected light at the end. Use an eraser to lift highlights on toned paper.

Pay attention to core shadow along the body’s curves; that dark band helps the figure feel solid. Keep cast shadows crisp where the body meets the surface to anchor the pose.

Designing the Composition

Place the figure using the rule of thirds or along a diagonal to add movement. Leave breathing room in the direction the model faces so the eye has a place to rest.

Simplify the background. A single tonal wash or a few gesture marks prevent clutter and keep focus on the figure. Use converging lines — edge of a rug, sling of drapery — to direct the eye toward key anatomical points.

Vary scale and crop thoughtfully. A three-quarter view can show anatomy and gesture, while a tight crop emphasizes form and surface texture. Maintain balance by contrasting dark areas with open light areas.

Developing Your Unique Style

You will combine influences, experiment with marks, and choose a consistent set of materials. Focus on what matters: subject choices, mark-making, value range, and the way you finish edges.

Finding Inspiration

Look closely at artists, photos, and life models to see what draws you. Study one artist’s way of handling light for a few weeks, then borrow a pose or a rhythm of lines. Notice recurring shapes, gestures, and value patterns that appeal to you.

Collect reference images, quick sketches, and notes in a small sketchbook. Mark what felt alive—was it a soft contour or a harsh shadow? Keep a folder of poses and tonal studies that work together visually.

Pay attention to mood and story. Decide whether you want quiet, formal studies or rough, expressive gestures. Let these choices guide your subject matter and the scale of your drawings.

Experimenting with Techniques

Try different charcoals: vine for soft tones, compressed for deep blacks, and pencils for fine lines. Work on a range of paper tones and textures to see how each affects contrast and edge clarity.

Test blending tools—fingers, stumps, cloth—and control how much you smudge. Practice three focused exercises: quick gesture drawings (1–2 minutes), mid-value block-ins (10–20 minutes), and finished tonal studies (1–3 hours). Track which exercise yields marks you like.

Vary your edges and line weight deliberately. Combine crisp contours with lost edges where form fades into shadow. When you find combinations that feel right, repeat them across several drawings to build a recognizable look.

Tips for Practice and Improvement

Practice with clear goals, regular sessions, and honest review. Set a simple plan for each session and track what you learn.

Setting Up Drawing Sessions

Choose short, focused blocks. Start with 10–20 minute gesture sketches to warm up, then spend 30–60 minutes on a study of one pose. Limit distractions: turn off notifications and arrange a small, clear workspace with your paper, vine charcoal, compressed charcoal, kneaded eraser, and blending stump within reach.

Use a mix of paper tones. Toned paper helps you practice midtones and highlights with white pastel or chalk. Vary the model distance. Move farther away to check proportions, then step closer to refine edges and textures.

Rotate exercises each week. One day focus on anatomy landmarks, another on value shapes, another on edges and line quality. Time yourself and keep a log of what you tried, what worked, and what to try next.

Reviewing and Reflecting on Your Work

Compare drawings side by side. Lay out your last five studies and note patterns: repeated proportion errors, shading habits, or successful marks. Write one or two bullet points under each drawing about the main problem and one fix for next time.

Use photos and mirror checks. Photograph a drawing and flip it horizontally to spot asymmetry. Examine your reference and drawing under different lighting conditions to verify values. Ask a peer or teacher one specific question, such as “Does the shoulder read as forward or back?”

Keep a sketchbook for notes. Jot quick insights after each session: what you learned, what felt hard, and a concrete next step. Revisit these notes monthly to measure progress and set new, realistic goals.

What techniques help improve figure drawing with charcoal?

Use loose, quick lines for gesture, block in large value areas, blend tones smoothly but retain some texture, measure proportions carefully, and practice varying edges and line weight to create dynamic and expressive drawings.

How do you approach the human form in charcoal drawing?

Begin with simple shapes and landmarks, map out bones and masses, study anatomy and proportions, and gradually refine with gesture, planes, and shading to capture movement and volume.

What materials are essential for starting charcoal nude figure drawing?

You need various types of charcoal, suitable paper that holds value and texture, erasers like kneaded and rubber ones, blending tools such as tortillons or stumps, and additional supplies like fixative spray and masking tape.

What are the different types of charcoal used in figure drawing?

Vine charcoal is soft and erasable, ideal for quick sketches; compressed charcoal is darker and denser, suitable for strong contrasts; and charcoal pencils are controlled tools for finer details.

What is charcoal nude figure drawing and how does it work?

Charcoal nude figure drawing involves depicting the human body on paper using charcoal sticks, pencils, or vine charcoal, focusing on shape, light, and posture to study anatomy, gesture, and value in an expressive way.

- 57shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest54

- Twitter3

- Reddit0