Your boat drawing looks like it’s hovering. The hull sits on top of the water like a paperweight on a desk—no displacement, no reflection, no sense that this vessel actually weighs anything.

I’ve noticed this is the single most common problem with boat drawings. Artists focus on getting the shape of the hull right (which is important), but they treat the water as an afterthought. They draw a wavy line underneath and call it done.

Here’s what they miss: a boat’s relationship with water is what makes it look like a boat. Without proper waterline placement, displacement curves, and reflections, you’re just drawing a floating shape. It could be a bathtub toy.

The oldest boats archaeologists have found are dugout canoes dating back 7,000-9,000 years. Humans have been building vessels to navigate water for millennia—and artists have been drawing them for nearly as long. Yet most boat drawing tutorials skip the fundamentals that make boats look convincing.

This guide covers what actually matters: hull construction using the figure-8 method, understanding how different boat types sit in water, and creating reflections that sell the illusion. We’ll work through specific vessel types—sailboats, fishing boats, speedboats, rowboats—because each has unique proportions and characteristics.

- Why Boats Are Harder to Draw Than They Look

- The Figure-8 Hull Method

- Boat Types and Their Distinct Proportions

- Step-by-Step: Drawing a Sailboat

- Step 1: Establish the Hull (2 minutes)

- Step 2: Add Perspective (2 minutes)

- Step 3: Establish the Waterline (1 minute)

- Step 4: Build Up the Hull (3 minutes)

- Step 5: Add the Mast and Boom (2 minutes)

- Step 6: Draw the Sails (3 minutes)

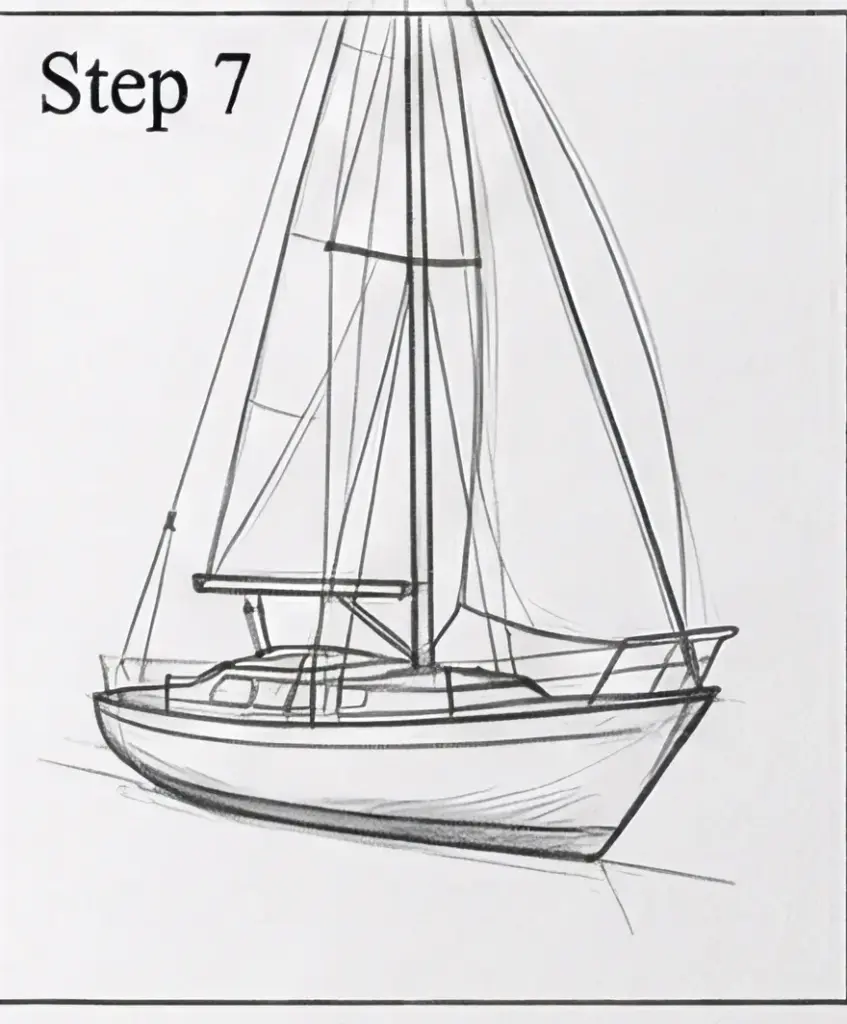

- Step 7: Add Rigging Details (2 minutes)

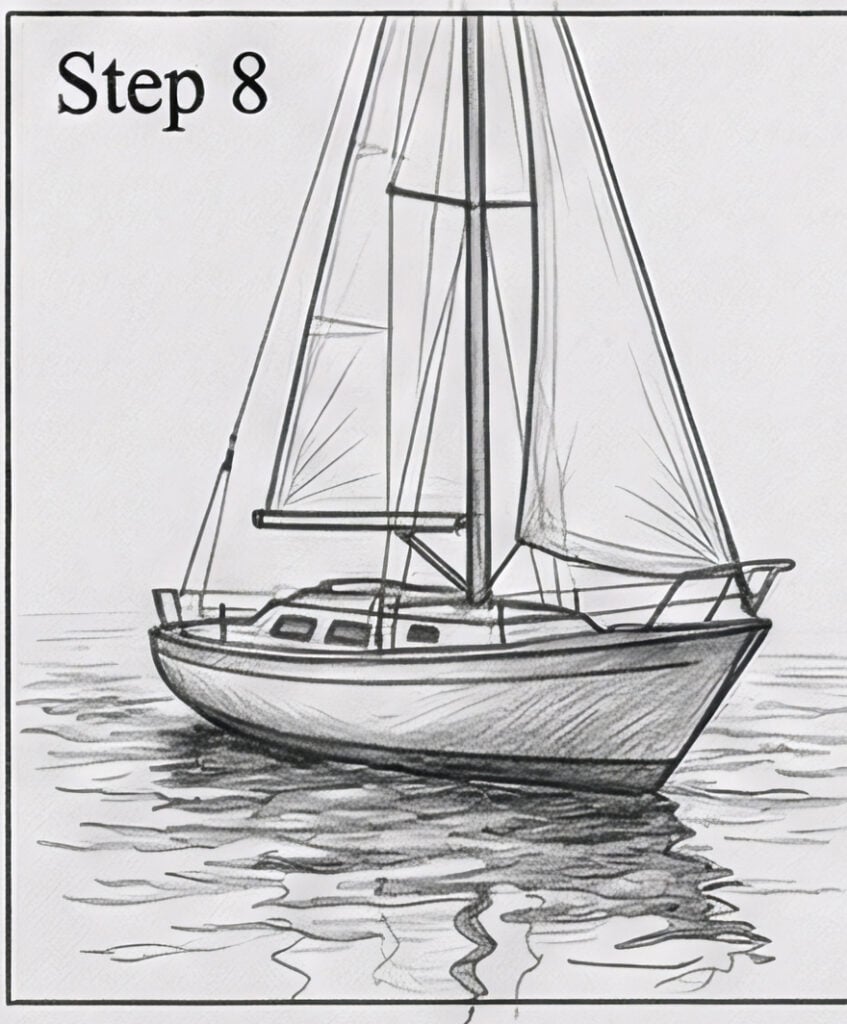

- Step 8: Water and Reflections (4 minutes)

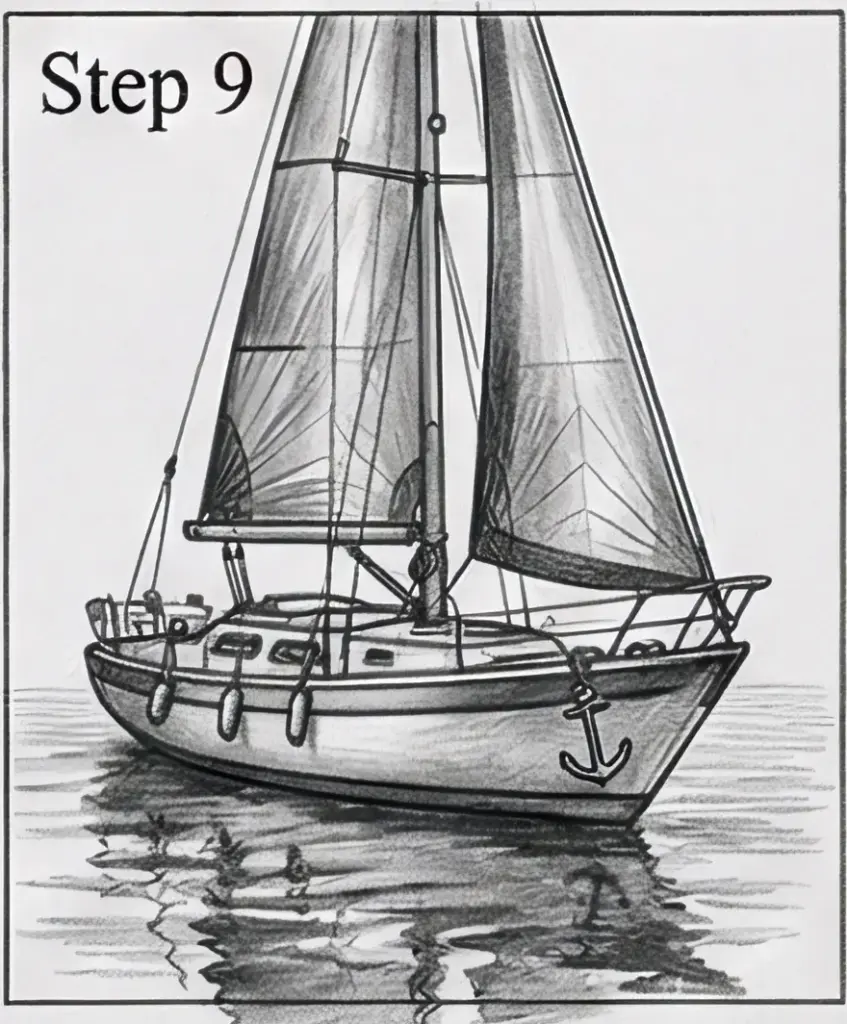

- Step 9: Final Details and Shading (3 minutes)

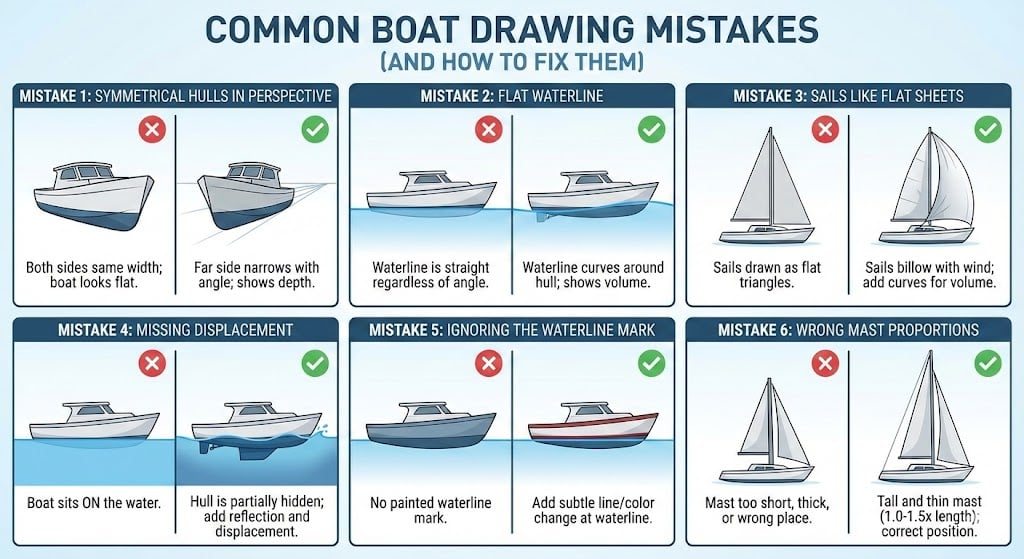

- Common Boat Drawing Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

- Drawing Water That Works

- Materials for Boat Drawing

- FAQ

- Conclusion

Whether you’re sketching a simple rowboat or tackling a full-rigged sailing ship, the principles are the same. Get the hull right first, then worry about details.

Why Boats Are Harder to Draw Than They Look

The Symmetry Problem

Boats are bilaterally symmetrical—the left and right sides mirror each other. That sounds simple until you try to draw one at an angle.

When you view a boat from directly in front or behind, symmetry is obvious. But from a three-quarter view (the most common and interesting angle), you’re seeing curves that wrap around a 3D form. The far side of the hull is compressed by perspective. The near side shows more surface area.

Most beginners draw both sides the same width regardless of viewing angle. The result looks flat, like a boat-shaped silhouette rather than a three-dimensional vessel.

The Curve Consistency Problem

Boat hulls are made of compound curves—curves that change direction smoothly along their length. The bow curves up and forward. The stern curves up and back. The sides curve outward from the keel and inward toward the gunwale.

These curves need to flow into each other without hard transitions. If you draw the bow with one curve type and the stern with another, the boat looks like it was built from mismatched parts.

The “Where’s the Water?” Problem

This is where most boat drawings fail completely. Artists draw the boat, then add water as a separate element—usually some wavy lines underneath.

But a boat in water displaces that water. The waterline isn’t a flat line; it curves around the hull. The hull below the waterline is hidden. Reflections appear directly beneath visible surfaces. Ripples radiate outward from the point of contact.

Without these elements, your boat isn’t in water—it’s floating above a blue surface.

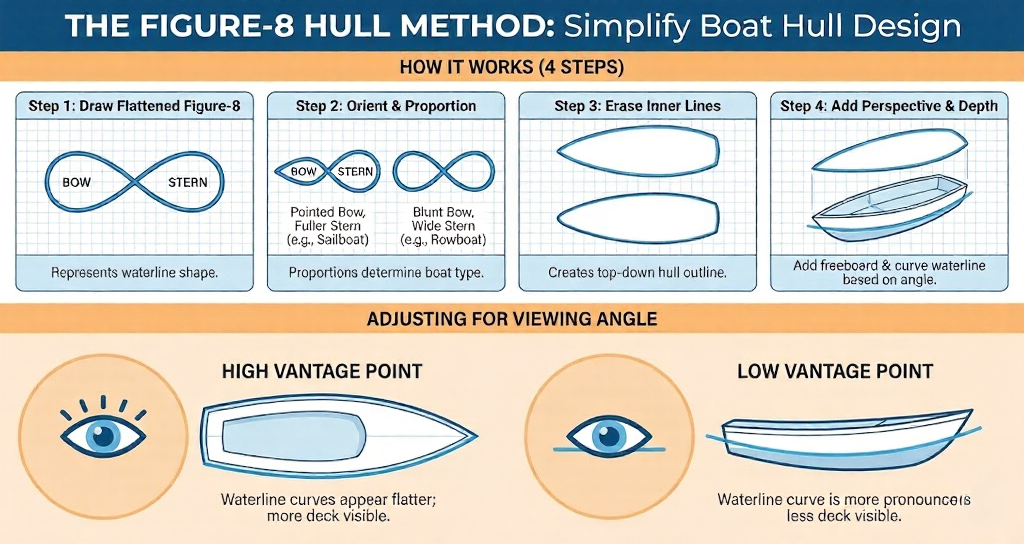

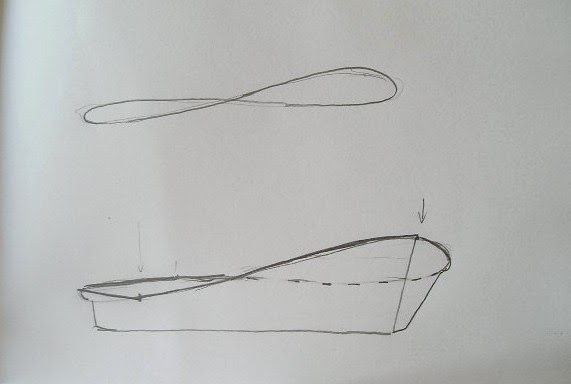

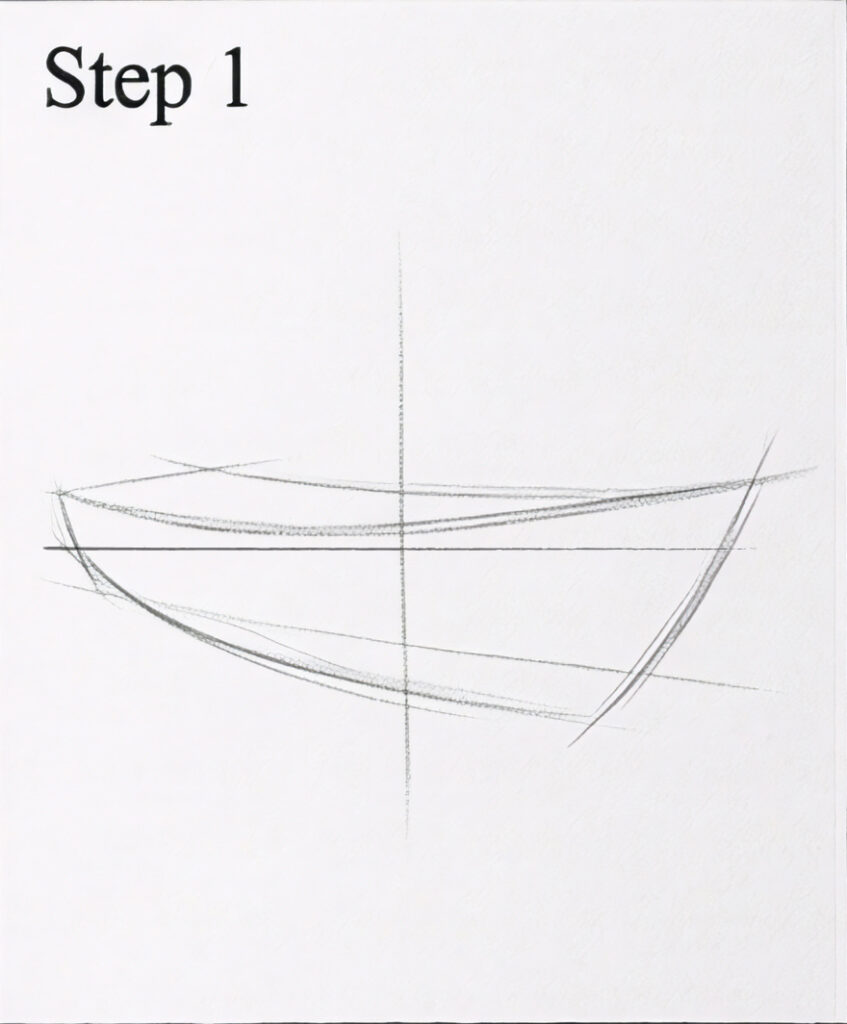

The Figure-8 Hull Method

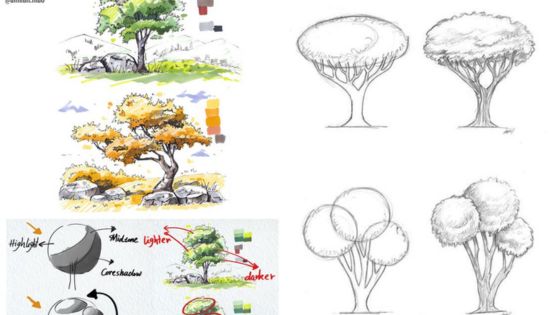

Professional marine artists and boat designers use a technique that simplifies hull construction dramatically. I learned this from studying boat plan drawings, and it’s transformed how I approach boat drawing.

How It Works

Start with a flattened figure-8 shape on its side. This single shape gives you the basic outline for most boat hulls—the curves naturally taper toward bow and stern while maintaining the proper beam (width) in the middle.

Step 1: Draw a horizontal figure-8, flattened like an elongated infinity symbol. The two “loops” represent the widest points of the hull at the waterline.

Step 2: Decide on orientation. Which end is the bow? For most boats, the bow is more pointed (narrower loop), the stern is fuller (wider loop). But this varies by vessel type.

Step 3: Erase the inner crossing lines. You’re left with the outline of a hull shape viewed from above.

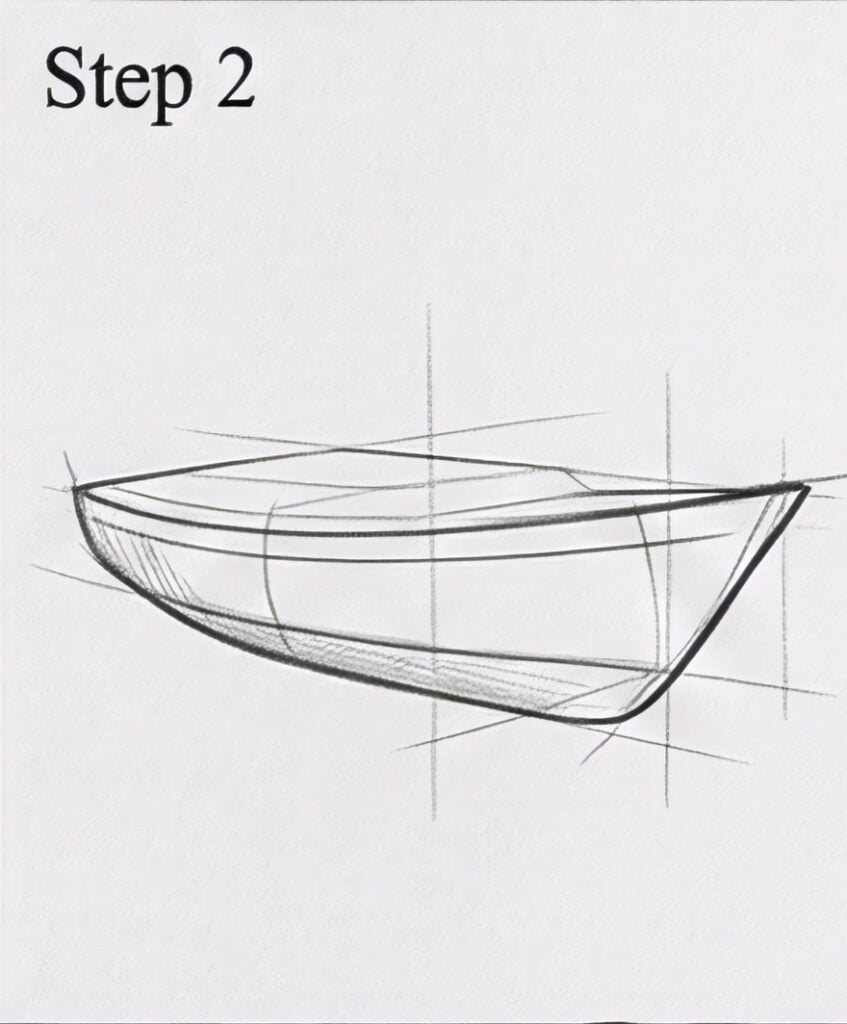

Step 4: Add perspective by narrowing the far side and raising or lowering the waterline depending on your viewing angle.

This method works for sailboats, rowboats, speedboats, and even larger vessels. The proportions of your initial figure-8 determine the boat type—narrow and long for a racing kayak, wide and short for a rowboat.

Adjusting for Viewing Angle

From a high vantage point, you see more of the deck and the waterline curves appear flatter. From a low vantage point (eye level with the water), the waterline curve is more pronounced—almost like a smile.

This is crucial for realism. Most beginners draw the waterline as a straight horizontal line regardless of perspective. But if you’re looking down at a boat, that waterline curves away from you. If you’re at water level, it curves toward you.

Boat Types and Their Distinct Proportions

Not all boats are built the same. Understanding the basic proportions of different vessel types helps you draw them accurately without reference photos.

Sailboats

Sailboats have deep hulls (to accommodate the keel) and relatively narrow beams compared to their length. The bow is usually sharper to cut through waves efficiently.

Key proportions:

- Length-to-beam ratio: typically 3:1 to 4:1

- Mast placement: usually 1/3 to 1/2 from the bow

- Hull depth below waterline: significant (keel extends well below)

- Freeboard (hull above waterline): moderate

The mast is the vertical centerline of a sailboat drawing. Get its position wrong, and the whole composition looks off-balance.

Sail shapes matter: A mainsail is roughly triangular but with a curved leech (back edge). A jib or genoa is also triangular but typically smaller. Sails aren’t flat—they curve to catch wind, creating a “belly” visible from the side.

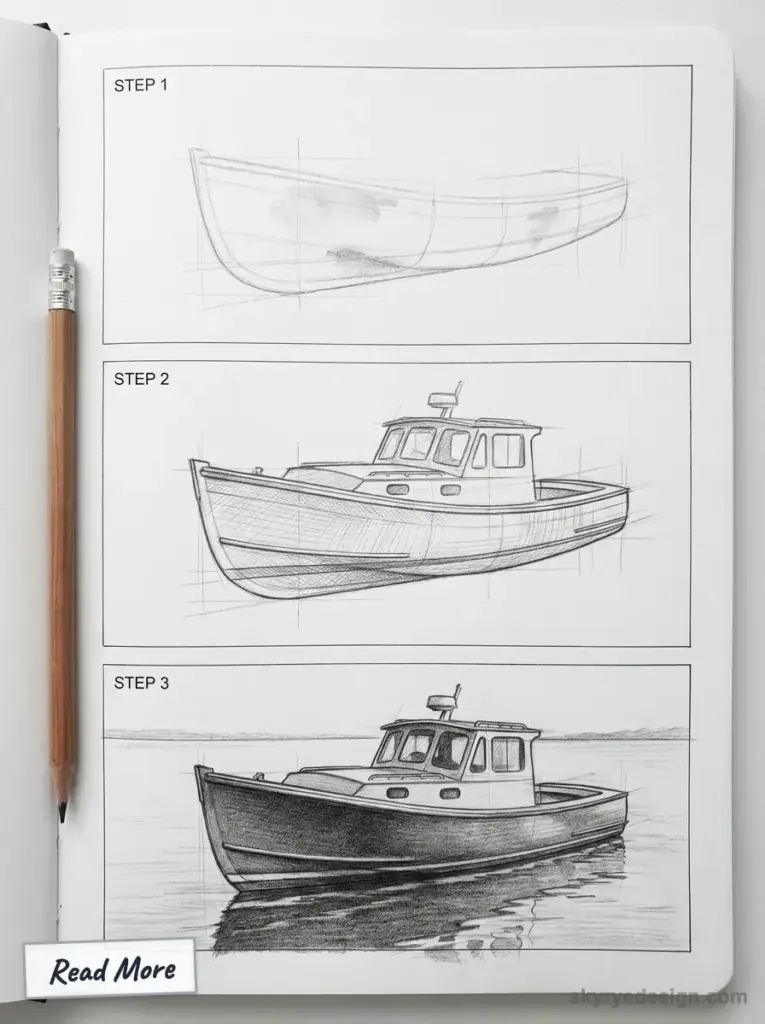

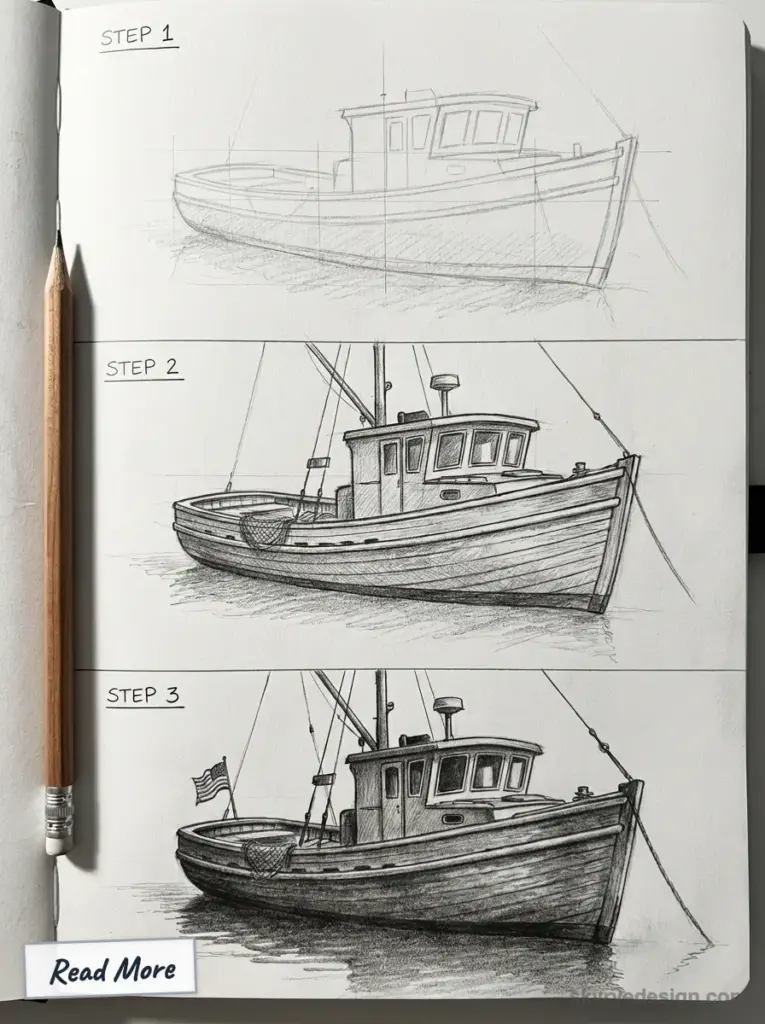

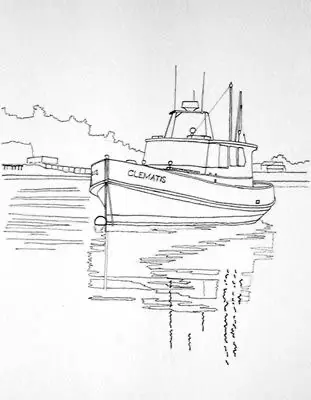

Fishing Boats and Trawlers

Fishing boats prioritize stability over speed. They have wider beams, flatter bottoms (in shallow-water designs), and more freeboard to accommodate gear and catch.

Key proportions:

- Length-to-beam ratio: typically 2.5:1 to 3:1

- Hull shape: often with a pronounced sheer (upward curve from midship to bow and stern)

- Cabin placement: usually toward the bow, leaving open deck space aft

- Working features: outriggers, nets, davits, A-frames

Fishing boats show their purpose. Include details like rod holders, livewells, or commercial equipment (nets, winches) to sell the type.

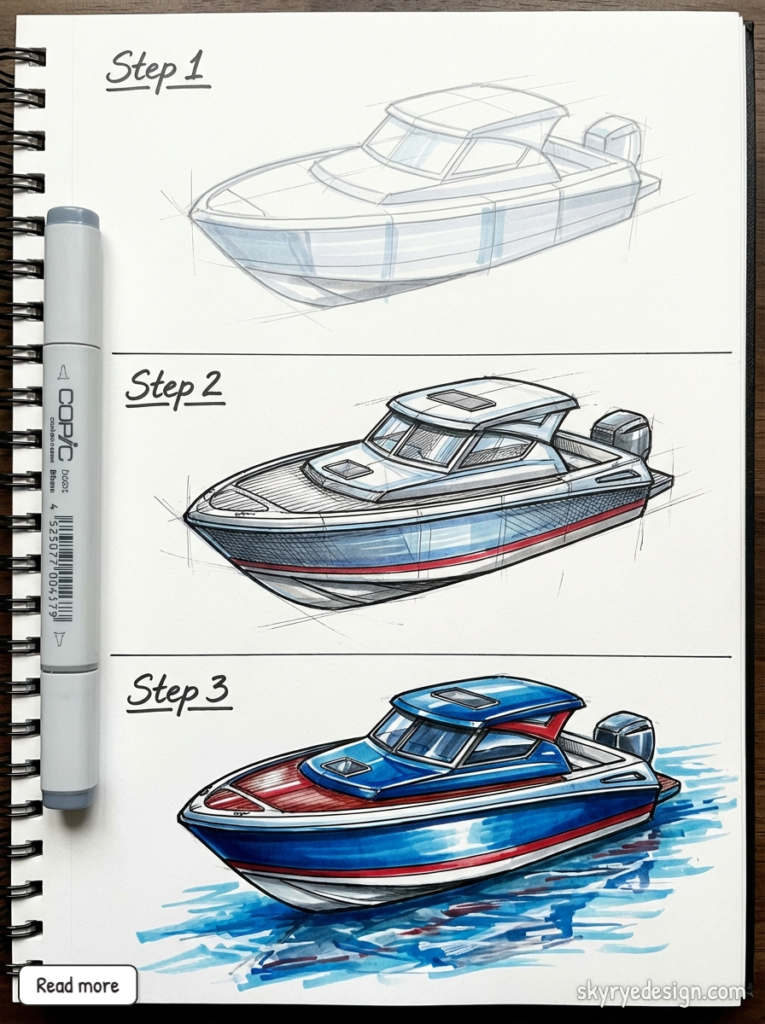

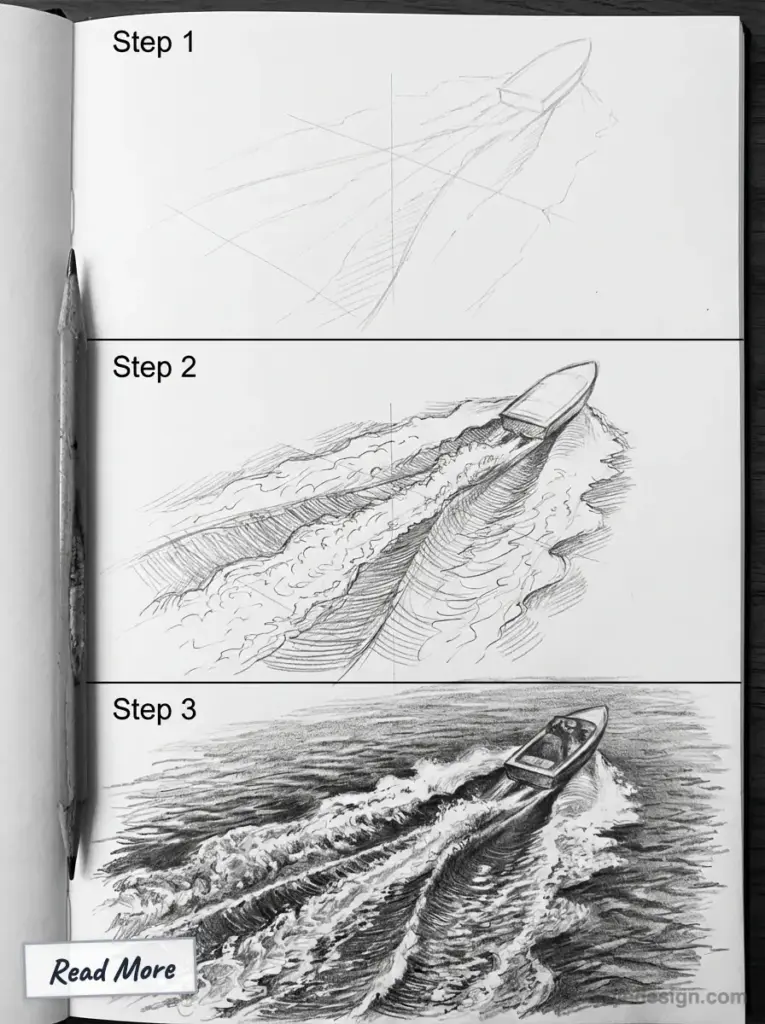

Speedboats and Runabouts

Speedboats have deep-V hulls designed to plane on top of the water at speed. The bow is sharply pointed and rises high. The stern is wide and flat for stability and to accommodate powerful outboard or inboard engines.

Key proportions:

- Length-to-beam ratio: varies widely, but often 3:1 to 4:1

- Bow angle: steep, often 20+ degrees

- Stern: wide, flat transom

- Windshield: prominent, often wraparound

When drawing a speedboat in motion, the bow rises and the stern digs in. The boat “planes” on the aft third of the hull, with the forward section out of the water.

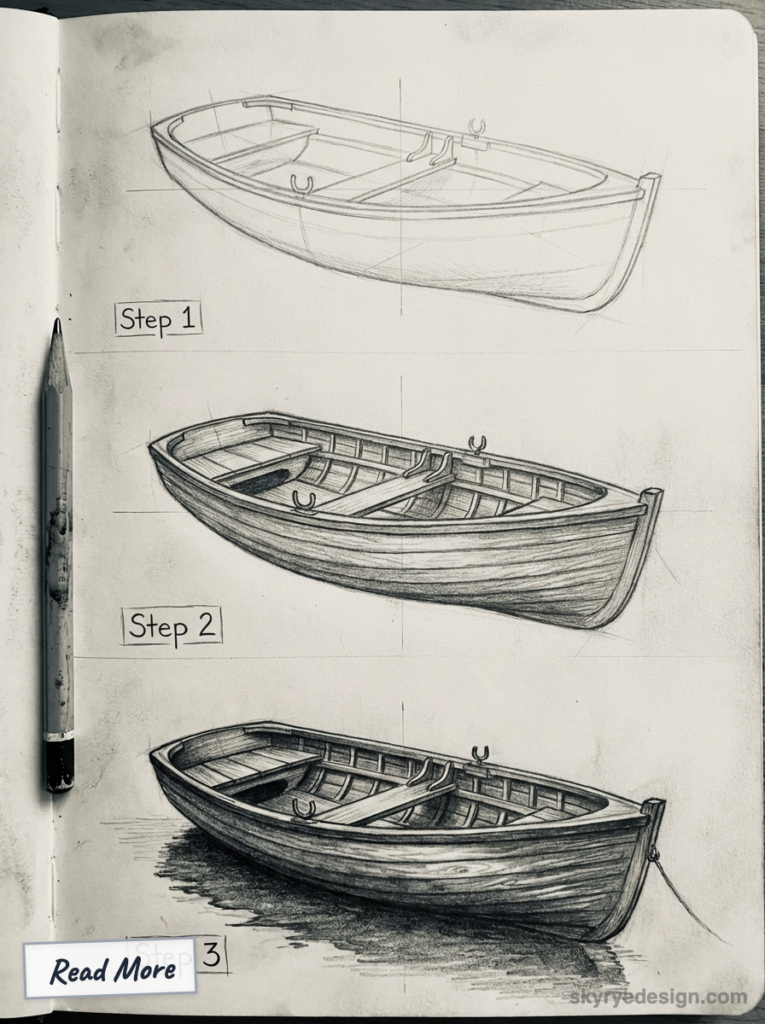

Rowboats and Dinghies

Small boats like rowboats, dinghies, and tenders are the simplest to draw—but that simplicity makes errors more obvious.

Key proportions:

- Length-to-beam ratio: typically 2:1 to 3:1

- Hull shape: rounded bottom (for stability) or flat bottom (for shallow water)

- Freeboard: low

- Features: oarlocks, thwarts (bench seats), possibly a small outboard mount on the transom

Rowboats sit low in the water. The waterline is high relative to the total hull depth. This low freeboard gives them their characteristic look.

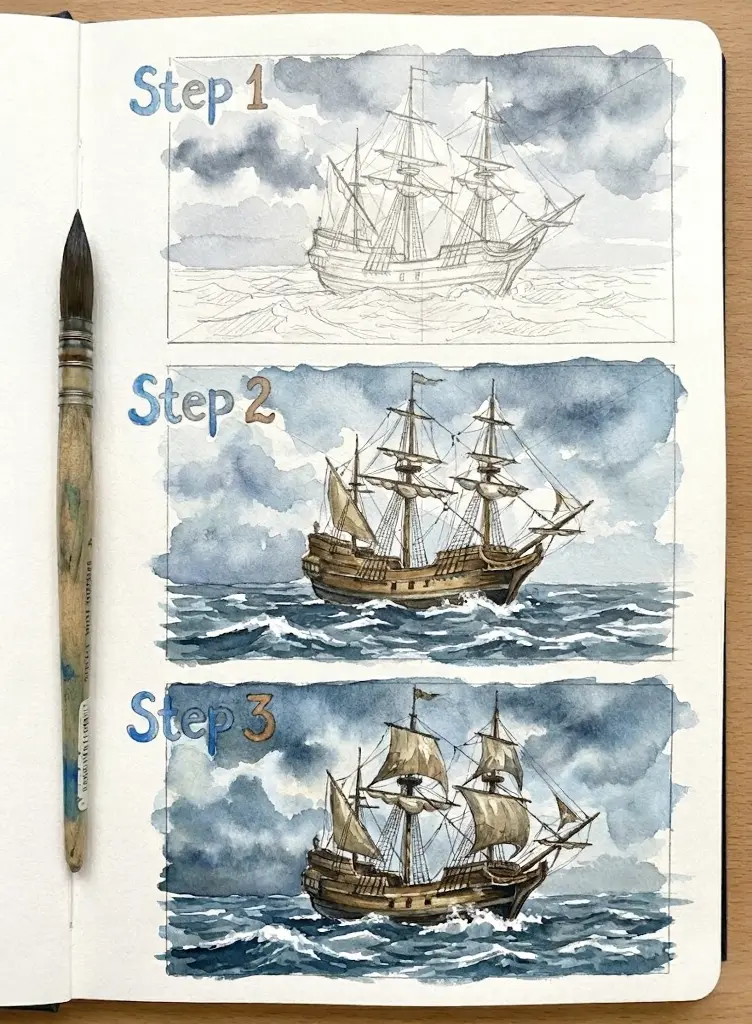

Historical Sailing Ships

Tall ships, schooners, and historical vessels are complex but follow predictable patterns. Multiple masts, extensive rigging, and decorative elements make them challenging—but the hull principles remain the same.

Key proportions:

- Hull shape: often with tumblehome (sides that curve inward above the waterline)

- Multiple masts: foremast, mainmast, mizzenmast, etc.

- Rigging: standing rigging (shrouds, stays) and running rigging (halyards, sheets)

- Decorative elements: figureheads, stern galleries, carved railings

For historical ships, accuracy matters to enthusiasts. Research the specific vessel type before committing to details.

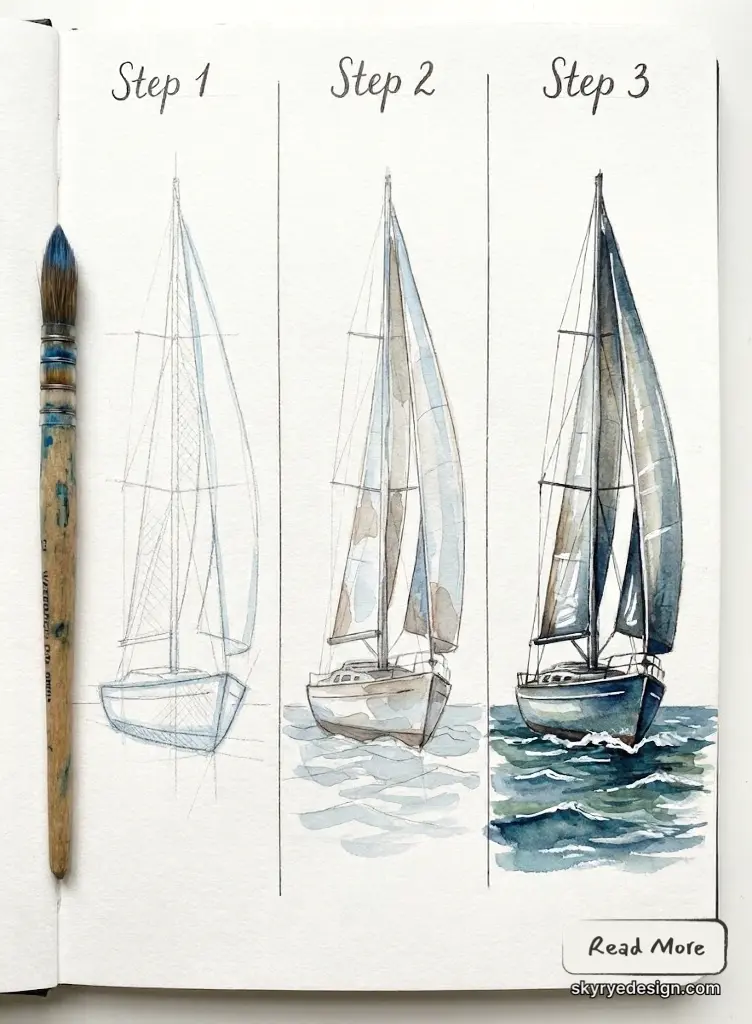

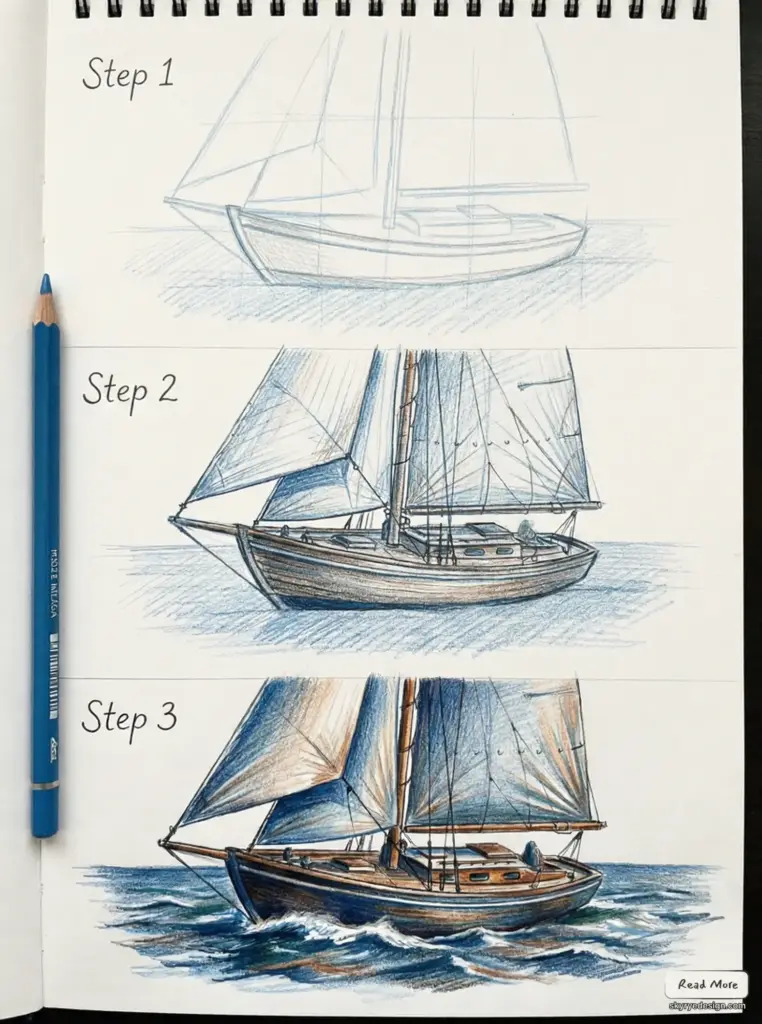

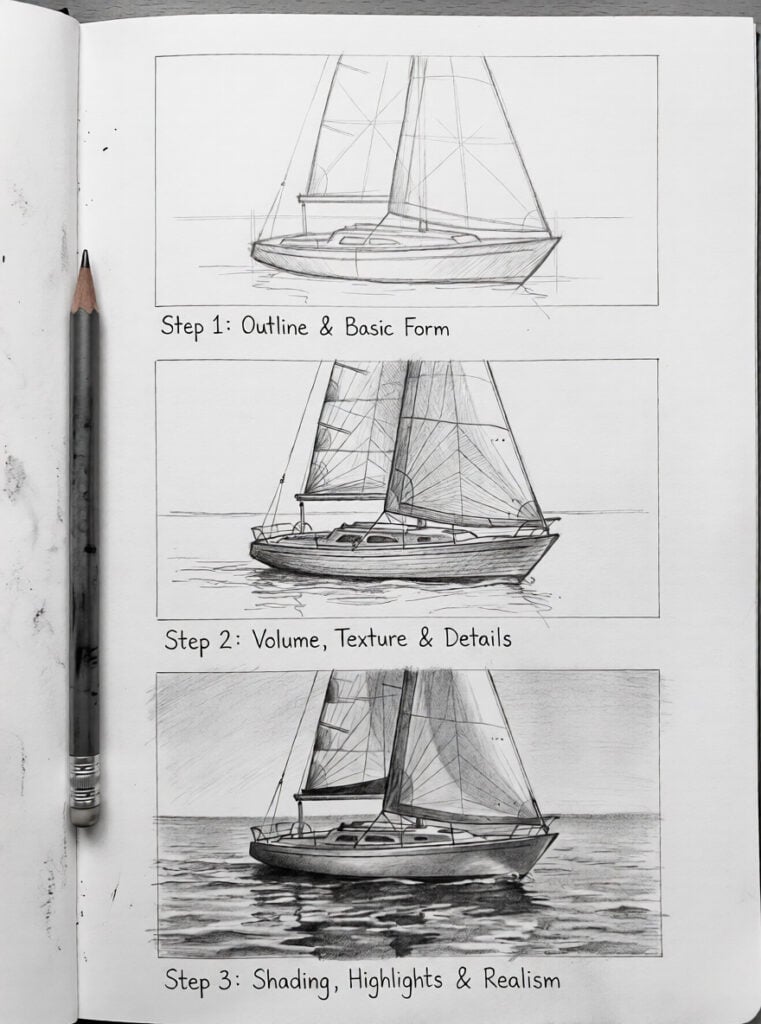

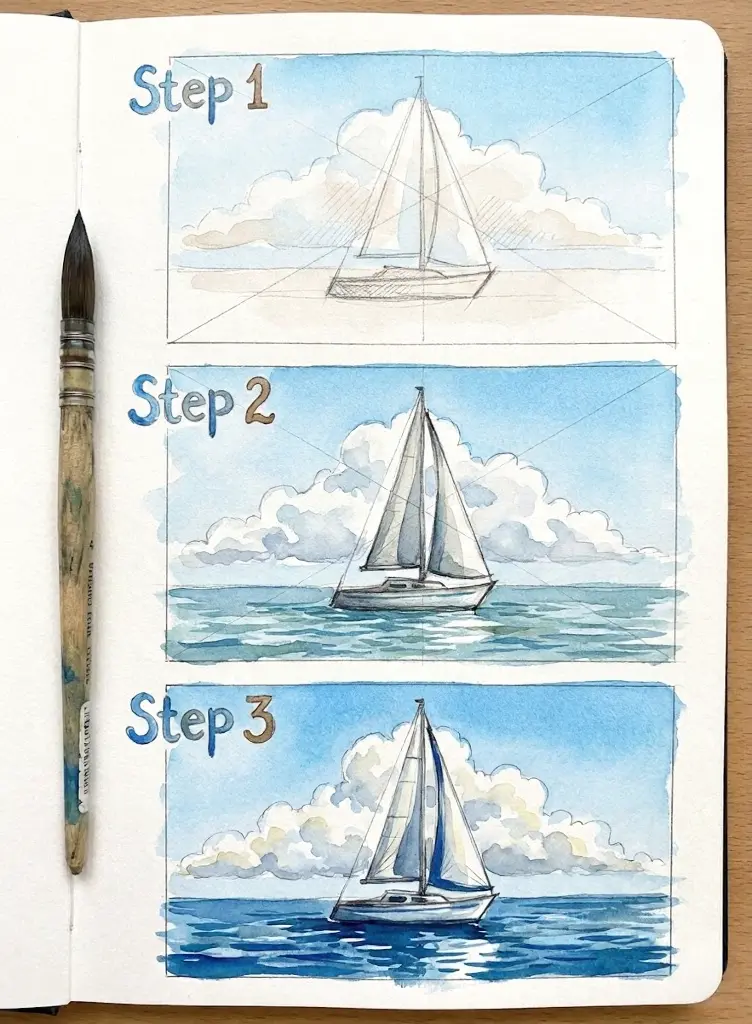

Step-by-Step: Drawing a Sailboat

Let me walk you through a complete sailboat drawing using the principles we’ve covered. This method takes about 15-20 minutes once you’re comfortable with it.

Step 1: Establish the Hull (2 minutes)

Draw a horizontal rectangle lightly—this is your bounding box. Now draw a flattened figure-8 inside it, with the narrower loop toward the left (this will be the bow).

Erase the inner crossing. You have your basic hull shape from above.

Step 2: Add Perspective (2 minutes)

Decide on your viewing angle. For a classic three-quarter view, narrow the far side of the hull and curve the near side more prominently.

Draw a vertical centerline from bow to stern. This helps maintain symmetry in perspective.

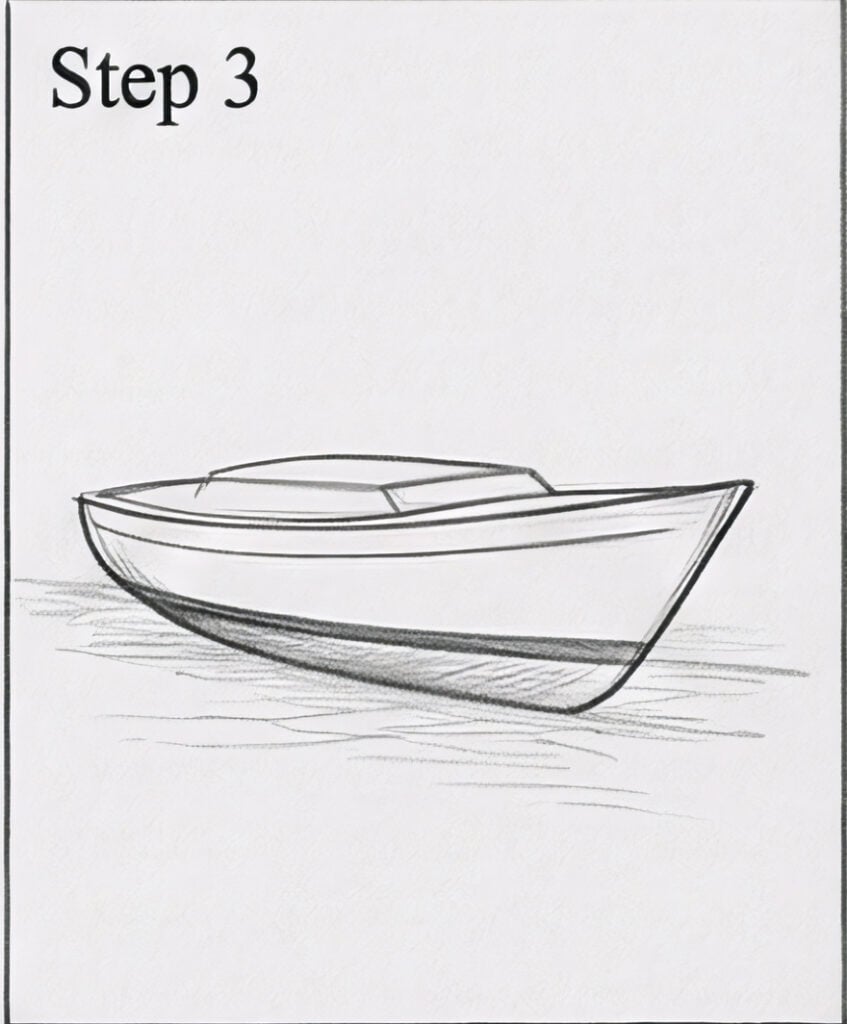

Step 3: Establish the Waterline (1 minute)

Draw a curved line across the hull where water meets the boat. Remember: high viewpoint = flatter curve; low viewpoint = more pronounced curve.

Everything below this line will be hidden or shown only as reflection.

Step 4: Build Up the Hull (3 minutes)

Add the gunwale (top edge of the hull sides). This follows the sheer—typically curving up slightly toward bow and stern.

Add the cabin or cockpit. For a simple sailboat, this is a low rectangular shape amidships. The top of the cabin should be below the level of the gunwale for visual balance.

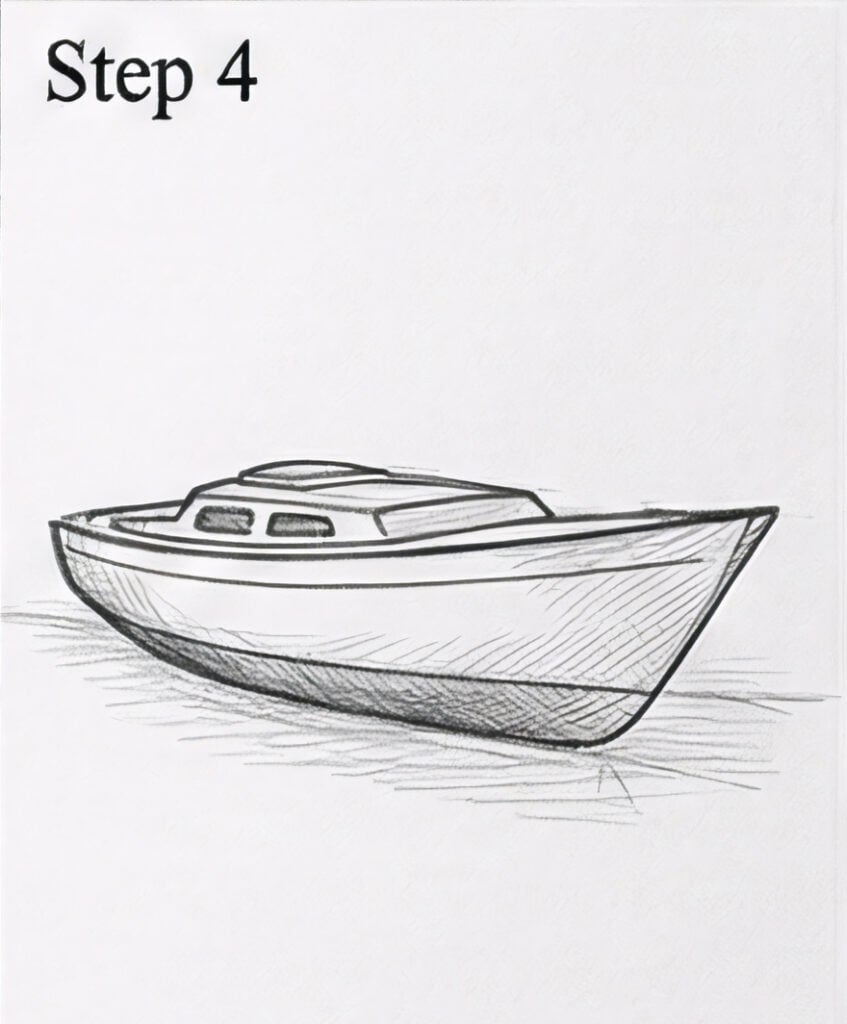

Step 5: Add the Mast and Boom (2 minutes)

Draw the mast as a vertical line rising from approximately 1/3 back from the bow. It should be perfectly vertical (or nearly so).

The boom extends horizontally backward from the base of the mast, parallel to the waterline.

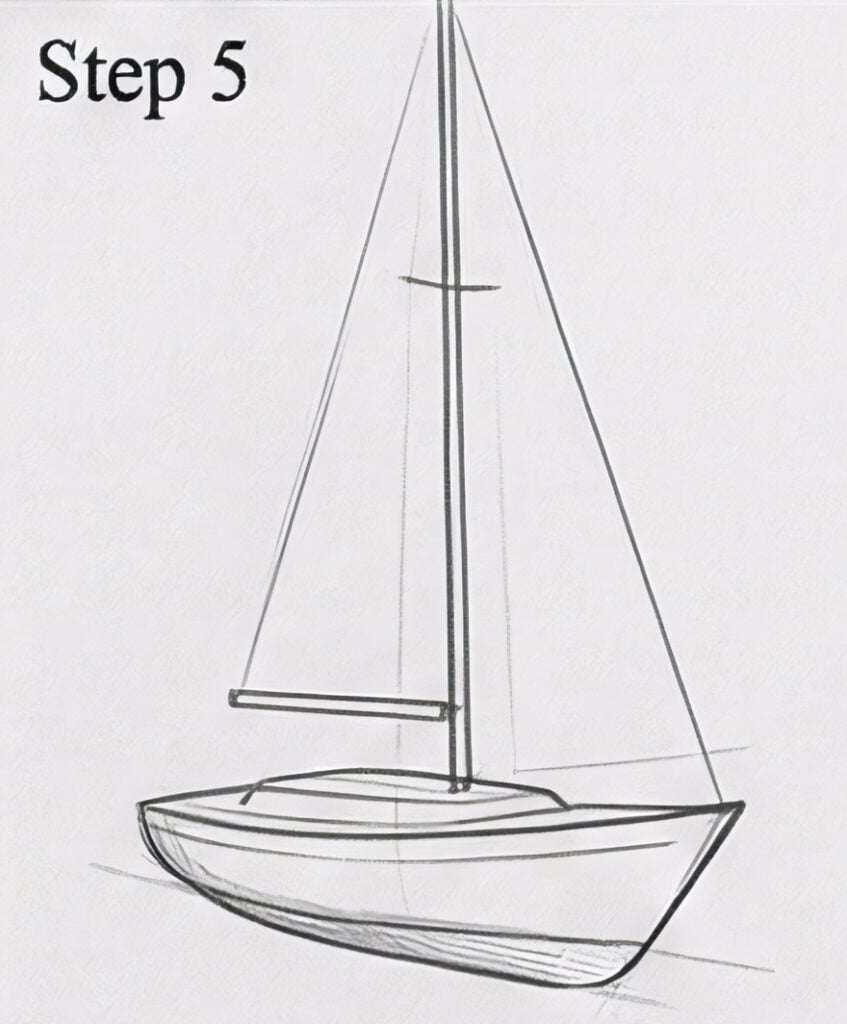

Step 6: Draw the Sails (3 minutes)

The mainsail connects: the top of the mast, the end of the boom, and a point partway up the mast (the head, clew, and tack). The sail should curve slightly to show wind.

If adding a jib, it runs from the top of the mast forward to the bow, then back to a point near the mast base.

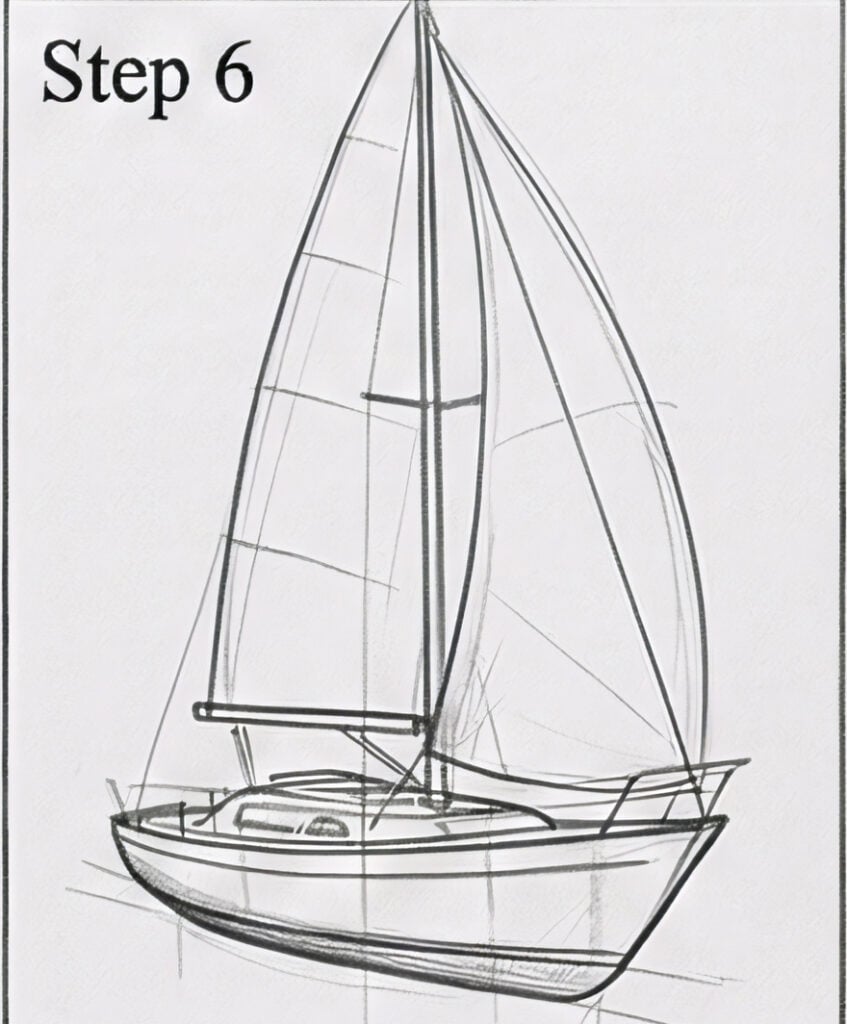

Step 7: Add Rigging Details (2 minutes)

Standing rigging includes shrouds (diagonal lines from mast to hull sides) and stays (lines from mast to bow and stern).

Running rigging includes halyards and sheets—but for most drawings, simple lines suggesting their presence is enough.

Step 8: Water and Reflections (4 minutes)

This is where most artists stop too early.

Draw the water surface with subtle horizontal lines or gentle wave shapes. Don’t overdo it—busy water competes with the boat.

Add a reflection directly below the hull. The reflection should be slightly wider than the actual hull (water distorts images) and broken up by ripples.

Include a waterline shadow where the hull meets the water—this is slightly darker than the surrounding water.

Step 9: Final Details and Shading (3 minutes)

Add shadows on the boat: the underside of the hull above waterline, beneath the boom, inside the cockpit.

Consider your light source. If the sun is from the upper right, the left side of sails and hull will be in shadow.

Final touches: porthole, name on transom, flag on mast, crew figures if desired.

Common Boat Drawing Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

Mistake 1: Symmetrical Hulls in Perspective

The problem: Both sides of the hull are the same width, making the boat look flat.

The fix: Always narrow the far side when drawing at an angle. The more extreme the angle, the more compression.

Mistake 2: Flat Waterline

The problem: The waterline is drawn as a straight horizontal line regardless of viewing angle.

The fix: The waterline curves around the hull. From above, it curves away from you. From water level, it curves toward you.

Mistake 3: Sails Like Flat Sheets

The problem: Sails are drawn as flat triangles when they should show volume.

The fix: Sails catch wind and billow. Add a gentle curve (convex on the wind side, concave on the lee side) to show this fullness.

Mistake 4: Missing Displacement

The problem: The boat appears to sit ON the water rather than IN it.

The fix: Hide the lower portion of the hull. Add a waterline shadow. Include a reflection. Show the water curving up slightly where it meets the hull.

Mistake 5: Ignoring the Waterline Mark

The problem: Real boats have a painted waterline mark, but drawings omit it.

The fix: Add a subtle line or color change at the waterline level. This immediately reads as “boat” and helps establish the water level.

Mistake 6: Wrong Mast Proportions

The problem: The mast is too short, too thick, or in the wrong position.

The fix: Mast height is typically 1.0 to 1.5 times the boat’s length for a sloop. Masts are thin relative to their height—think flagpole, not telephone pole.

Drawing Water That Works

Water is the hardest part of boat drawing, so let’s address it directly.

Calm Water

For calm water, less is more. Subtle horizontal lines suggesting the surface. Slight tonal variation. A clean reflection below the boat.

Don’t draw individual waves unless there’s wind or wake. Calm water is almost mirror-like—the reflection is nearly perfect.

Choppy Water

Choppy water breaks up reflections. Instead of a clean mirror image, you get fragments of color and value appearing in wave troughs.

Draw waves as overlapping curves, with the nearest waves larger and more detailed than distant ones. Waves have highlights on their crests and shadows in their troughs.

Wake and Motion

A moving boat creates wake—V-shaped waves spreading outward from the bow and a churned area behind the stern.

For speedboats, the wake is dramatic: spray at the bow, rooster tail at the stern. For sailboats, it’s subtler: clean bow wave, slight disturbance astern.

The faster the boat, the higher the bow rises and the more pronounced the wake.

Reflections

Boat reflections follow rules:

- They appear directly below the object

- They’re slightly wider than the object (water distortion)

- They’re broken up by surface ripples

- Colors are slightly darker and less saturated than the actual object

- They extend downward from the waterline, not upward

The most convincing reflections are simplified versions of the boat above—just enough detail to read as a reflection, not a precise mirror copy.

Materials for Boat Drawing

For Pencil Work

Graphite pencils: A range from 2H (light construction lines) to 6B (dark shadows and details). HB or 2B for general work.

Mechanical pencil: 0.5mm for fine rigging and detail work.

Kneaded eraser: Essential for lifting highlights in reflections and water.

Blending stumps: For smooth gradations in hull shading and water.

Paper: Smooth Bristol for detailed technical work; medium-tooth drawing paper for more textured effects.

For Ink Work

Technical pens: 0.1mm to 0.5mm for varying line weights. Thicker lines for near objects, thinner for distant and details.

Brush pens: For organic shapes like sails and waves.

For Color Work

Watercolors: Ideal for boats—you’re already dealing with water themes. Wet-on-wet technique works well for water; wet-on-dry for boat details.

Colored pencils: Allow precise control for detailed work. Layer blues and greens for water; save white paper for highlights.

Markers: Copic or similar alcohol markers for bold, graphic boat illustrations. Quick coverage but less forgiving than pencil or watercolor.

FAQ

What’s the easiest boat to draw for beginners?

A simple rowboat or dinghy. They have uncomplicated shapes—essentially an elongated oval with raised sides—no mast, no rigging, minimal details. You can practice hull shapes, waterline placement, and reflections without complex superstructure. Once you’re comfortable with rowboats, move to sailboats (adds mast and sails) and then to more complex vessels. Master the hull first; details come easier after.

How do I make my boat look like it’s actually floating?

Three elements create the floating illusion: waterline placement (hide the bottom of the hull), displacement shadow (darker water where hull meets surface), and reflection (simplified mirror image below the boat, broken by ripples). Most failed boat drawings include the hull but skip these three elements. Add them even roughly, and the boat immediately looks like it’s in water rather than above it. The reflection doesn’t need to be detailed—just suggest the hull’s shape and color.

Why do my sailboat sails look wrong?

Usually it’s one of two issues: sails are drawn flat (they should curve to show wind pressure) or proportions are off (mainsail too small relative to boat length). A filled sail has a visible belly—convex on the windward side, concave on the lee side. Also check that your sail attachments make sense: mainsail connects to mast and boom, jib runs from masthead to bow. If sails look like flat triangles stuck to poles, add that curve.

How do I draw a boat from different angles?

Use the figure-8 method as your starting point for any angle. For a side view (profile), you see the hull’s length but minimal width—the figure-8 becomes a simple curve. For a front view, you see the beam but minimal length—the figure-8 becomes almost circular. For three-quarter views (most dynamic), the far side of the hull compresses while the near side shows full curvature. Practice drawing the same boat from multiple angles to understand how the hull form changes with perspective.

What details make a boat drawing more realistic?

Functional details that show the boat’s purpose: On sailboats—cleats, winches, blocks (pulleys), telltales on sails. On fishing boats—rod holders, outriggers, livewells, fish boxes. On all boats—a proper waterline mark (usually painted), anchor and rode, fenders, dock lines. Avoid adding details you don’t understand. Research the specific boat type; adding accurate details shows knowledge, while wrong details immediately flag your drawing as uninformed.

How long should it take to get good at boat drawing?

Most people see significant improvement after 15-20 focused attempts—not hours, but completed drawings. Start with simple boats (rowboats, dinghies) and do 5-6 of those before attempting sailboats. Spend 3-4 attempts just on hulls and waterlines before adding details. Within a month of regular practice (even 15-20 minutes daily), you should be producing boats that convincingly sit in water. Complex vessels like tall ships take longer—expect several months of regular practice for proficiency.

Conclusion

Every boat drawing fails or succeeds at the waterline. You can have perfect rigging, beautiful sails, immaculate detail work—but if that hull is sitting on top of the water instead of in it, the drawing falls apart.

Here’s your starting sequence:

Today: Draw five hull shapes using the figure-8 method. Don’t add any details—just practice getting the basic form right from different angles.

This week: Add waterlines and reflections to those hulls. Practice the displacement shadow. Make your shapes look like they’re floating, not hovering.

Next week: Pick one boat type (I’d suggest a simple sailboat) and draw it ten times. Same boat, different angles, different conditions. Get to know that vessel.

The artists who draw convincing boats aren’t working from magic—they understand hull construction, water behavior, and perspective. These are learnable skills, not innate talents.

I’ve found that boat drawing is uniquely satisfying once you understand the fundamentals. There’s something about capturing a vessel that floats, that moves through water, that carries people toward destinations. It’s an object with purpose and history.

Your sketchbook is waiting. Start with the hull.

- 3.6Kshares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest3.6K

- Twitter3

- Reddit0