A great white shark can swim 35 miles per hour. On paper, it moves at exactly the speed of your pencil—which is both the challenge and the freedom of drawing these animals.

Here’s the thing about shark drawings that most tutorials skip: sharks aren’t just fish with teeth. They’re 450 million years of evolution compressed into a shape so aerodynamically perfect that engineers still study them for submarine design. When you draw a shark, you’re drawing one of nature’s most refined forms. Get it wrong and your shark looks stiff, dead, frozen. Get it right and the thing practically swims off the page.

I’ve noticed that beginners often start with the mouth—those famous teeth. But teeth are the easy part. The hard part? Making a 2,000-pound predator look like it’s actually moving through water, not posing for a photo. That takes understanding structure, not just copying shapes.

- Why Sharks Are Harder to Draw Than You Think

- Shark Anatomy for Artists: What Actually Matters

- Drawing Different Shark Species: Key Visual Differences

- Step-by-Step: Basic Shark Drawing Method

- Style Variations for Shark Drawings

- Common Mistakes in Shark Drawings (And How to Fix Them)

- Materials for Shark Drawings

- Sharing Your Shark Drawings

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What's the easiest shark to draw for beginners?

- How do I make my shark look like it's actually swimming?

- What references should I use?

- Can I draw cartoon sharks without learning realistic anatomy?

- How long does it take to get good at drawing sharks?

- What's the most common mistake professional artists see in beginner shark drawings?

- Your Next Steps

This guide breaks down shark anatomy for artists, covers the key differences between species you’ll actually want to draw, and walks through techniques that work across styles—from quick sketches to detailed studies. Let’s build some predators.

Why Sharks Are Harder to Draw Than You Think

Most artists draw sharks like they draw other fish: start with an oval, add fins, done. That approach works for a goldfish. It doesn’t work for an animal whose entire body is a weapon.

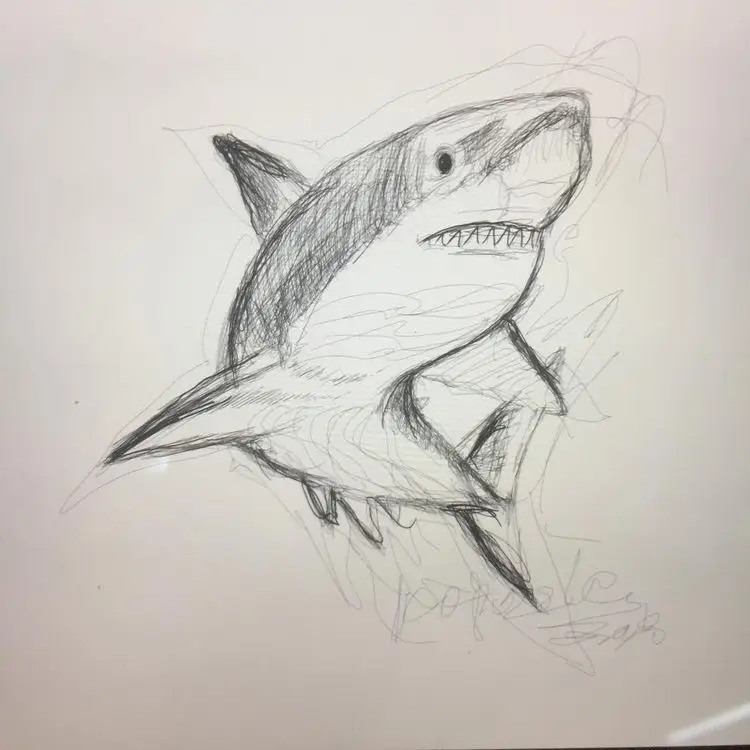

The Movement Problem

Sharks never stop moving. Literally—many species need constant forward motion to breathe. This creates the central challenge of shark drawings: how do you capture perpetual movement in a still image?

I’ve found that the answer isn’t in the pose—it’s in the lines. Flowing, curved lines suggest motion. Stiff, geometric lines suggest a taxidermy mount. Compare the amateur shark drawings on Pinterest to professional work by artists like Aaron Blaise (former Disney animator who now teaches wildlife drawing), and you’ll see the difference immediately. The pros use rhythm in their line work.

Quick test for your own work: Cover the fins with your hand. Does the body still look like it’s moving? If yes, you’re on the right track.

study these features. Sketching often begins with simple shapes to outline the shark’s body. Then, details are added to showcase unique characteristics. This process helps create a more accurate representation in the final artwork.

The Water Problem

Sharks exist in water. Obvious, but artistically critical. Water affects everything: how light hits the body, how fins trail, how the eye perceives depth. A shark floating in white space looks wrong even if the anatomy is perfect.

You don’t need to draw an entire ocean. But you need to imply water through:

- Subtle shading gradients (lighter on top, darker below—opposite of how light works on land)

- Trailing movement lines near fins and tail

- Slight blur on background elements

- Color temperature shifts (cooler in shadows, warmer where light penetrates)

Shark Anatomy for Artists: What Actually Matters

You don’t need a marine biology degree to draw convincing sharks. You need to understand five key anatomical features that define the silhouette and movement.

1. The Torpedo Body

Every shark species shares a basic body plan: a torpedo. Front end narrow, middle thick, back end tapered. But the exact proportions vary dramatically.

Great white: Bulkier, more mass in the middle third. Think linebacker.

Mako: Sleeker, more evenly distributed. Think Olympic swimmer.

Whale shark: Massive, blunt head, body stays thick almost to the tail. Think school bus.

When sketching, start with a simple oval, then push and pull it toward your target species. I spend about 30 seconds just getting this foundation shape right before adding anything else.

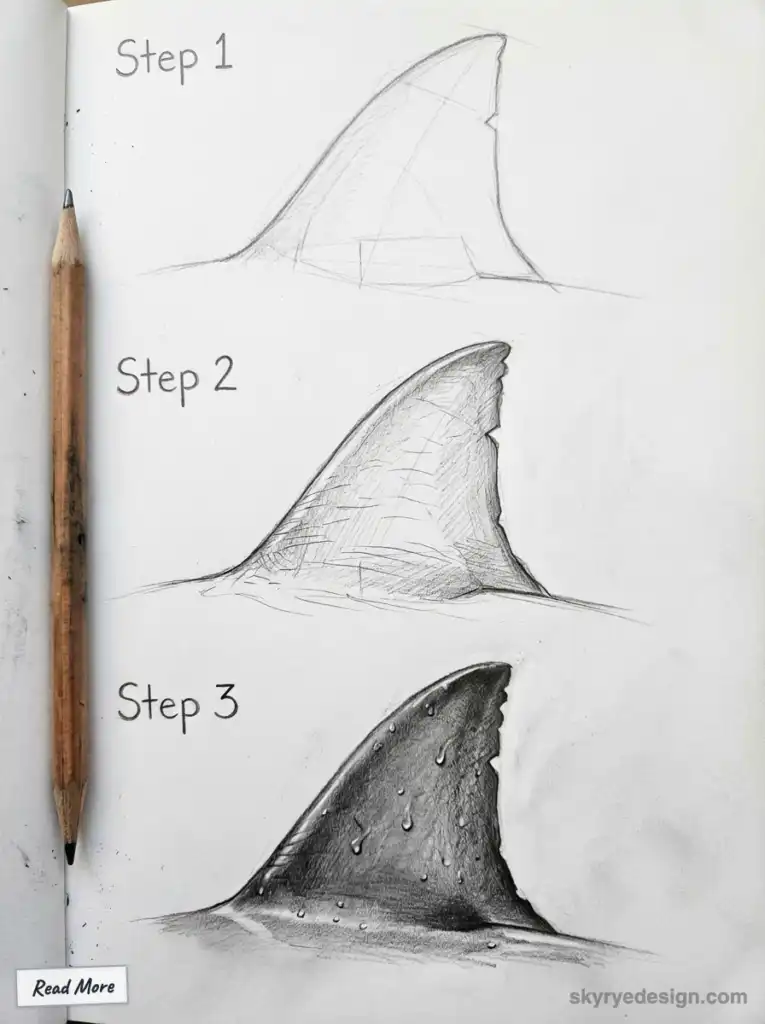

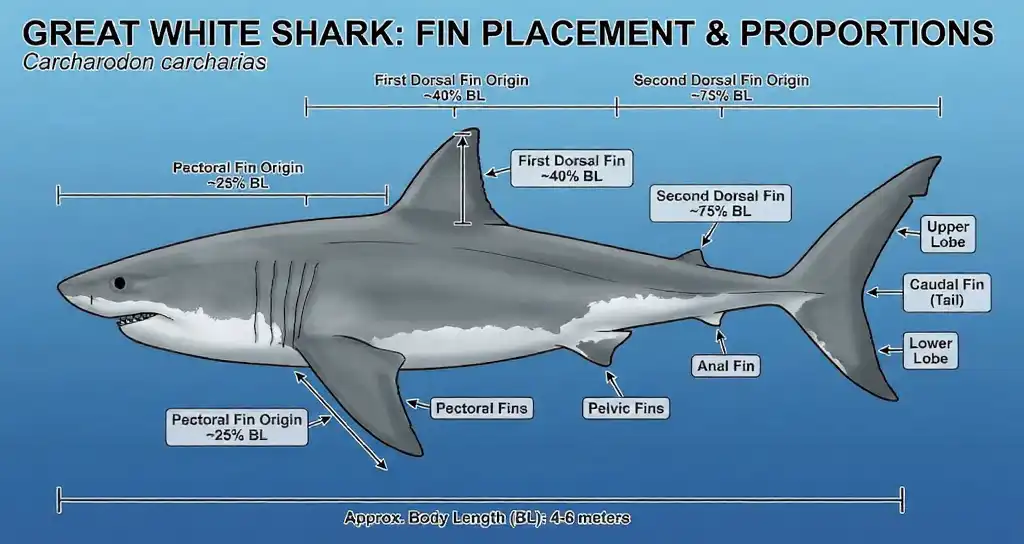

2. The Fin Placement

Fins aren’t decoration—they’re engineering. Their placement and angle communicate everything about what the shark is doing.

Dorsal fin: The iconic one. Sits roughly at the body’s highest point. When erect, the shark is cruising. When laid back, it’s accelerating or diving.

Pectoral fins: The “wings.” These control lift and turning. Angled up = rising. Angled down = diving. Swept back = speed.

Caudal fin (tail): The engine. Upper lobe typically larger than lower in most species. The angle of the tail indicates thrust direction.

Common mistake: Placing the dorsal fin too far forward. Check reference photos—it’s usually further back than you expect.

3. The Mouth Position

Sharks have underslung mouths—they sit below the snout, not at the front of the head like many fish. This is crucial for the side view and three-quarter angle that most artists draw.

The exact mouth position varies by species:

- Great white: Relatively forward, visible from the side

- Hammerhead: Underneath the cephalofoil (the hammer), barely visible from above

- Whale shark: Massive, at the front of a flattened head

- Tiger shark: Blunt snout, mouth relatively forward

4. The Gill Slits

Sharks have 5-7 gill slits (depending on species) on each side, just behind the head. These vertical lines are a dead giveaway of “shark” versus “generic fish.” Include them.

Position: Behind the eye, before the pectoral fin. They follow the curve of the body, not straight vertical lines.

5. The Eye

Shark eyes are smaller than you’d think and positioned for maximum field of view. Most species have eyes on the sides of the head, giving them nearly 360-degree vision.

For expressions:

- Predatory focus: Smaller pupil, eye angled slightly forward

- Curious/alert: Larger eye area, visible sclera

- Aggressive: Nictitating membrane (third eyelid) partially covering the eye

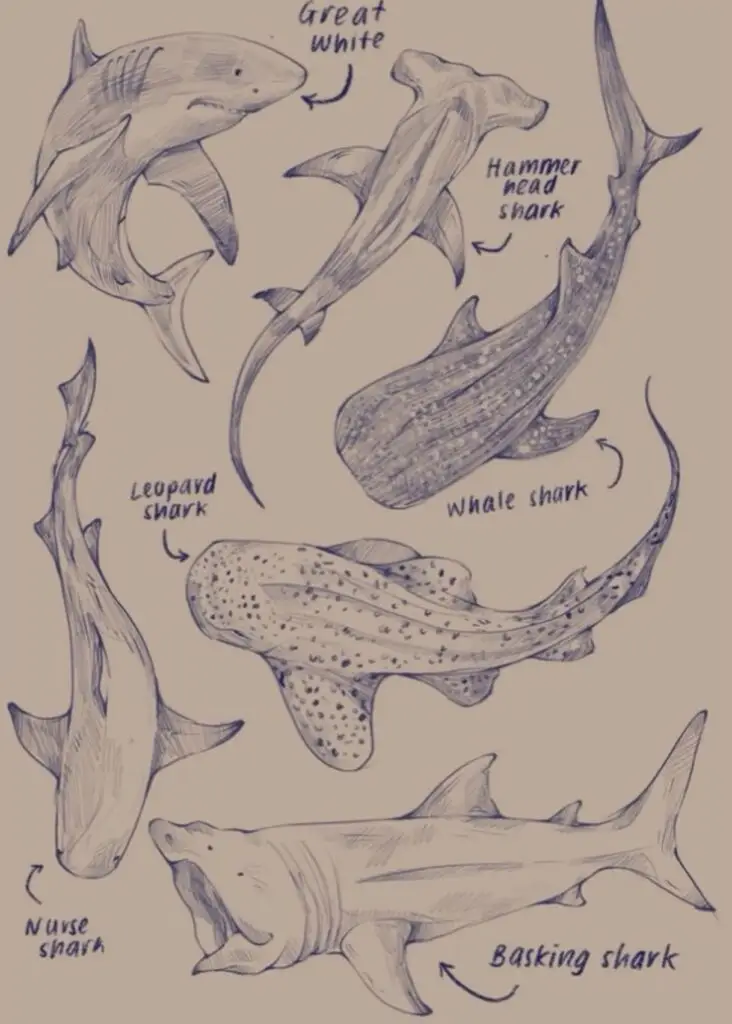

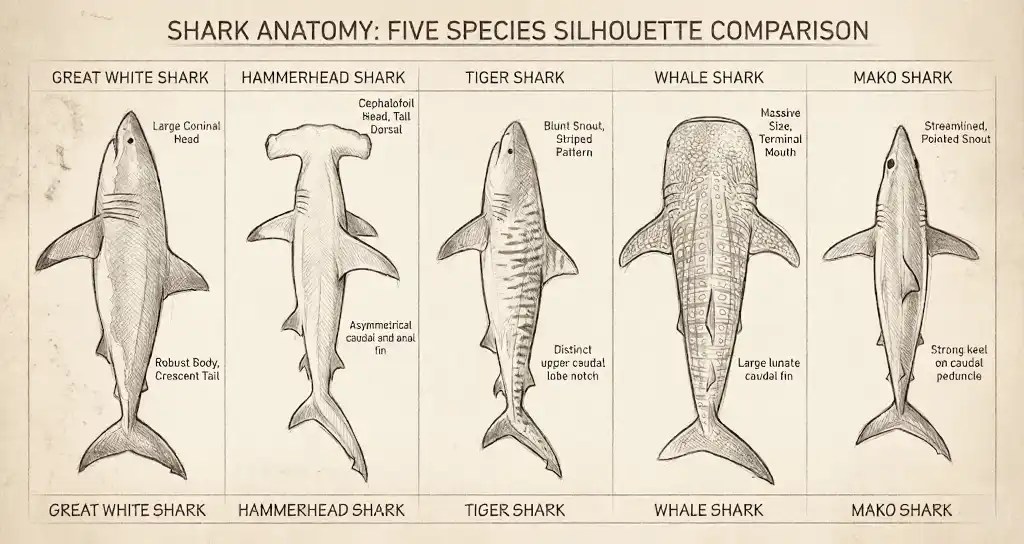

Drawing Different Shark Species: Key Visual Differences

Not all sharks look alike. Here’s what makes each major species distinct—the features that viewers will recognize (or notice are wrong).

Great White Shark

The one everyone wants to draw. Made famous by Jaws, instantly recognizable.

Key features:

- Conical snout, relatively pointed

- Heavy body, particularly in the mid-section

- Triangular, serrated teeth (visible even when mouth closed)

- Dark gray-blue on top, stark white below (countershading)

- Black eyes—no visible sclera

- First dorsal fin large and triangular

Artist’s tip: The great white’s power comes from its bulk. Don’t make it too streamlined—it should look heavy and muscular.

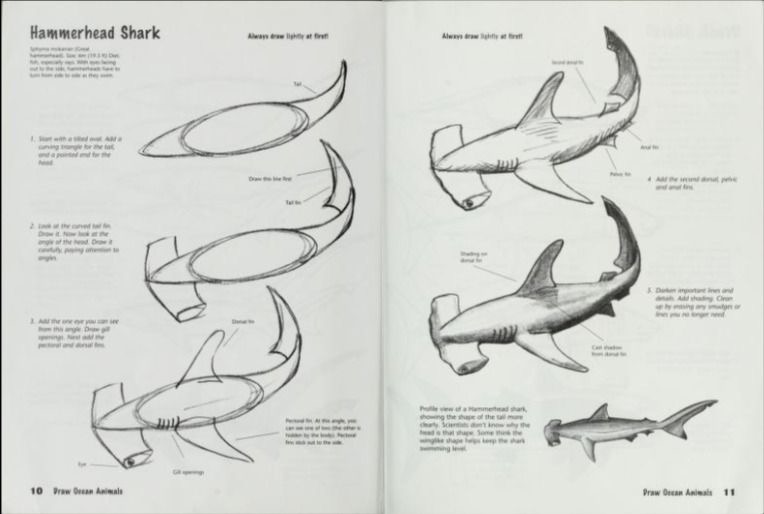

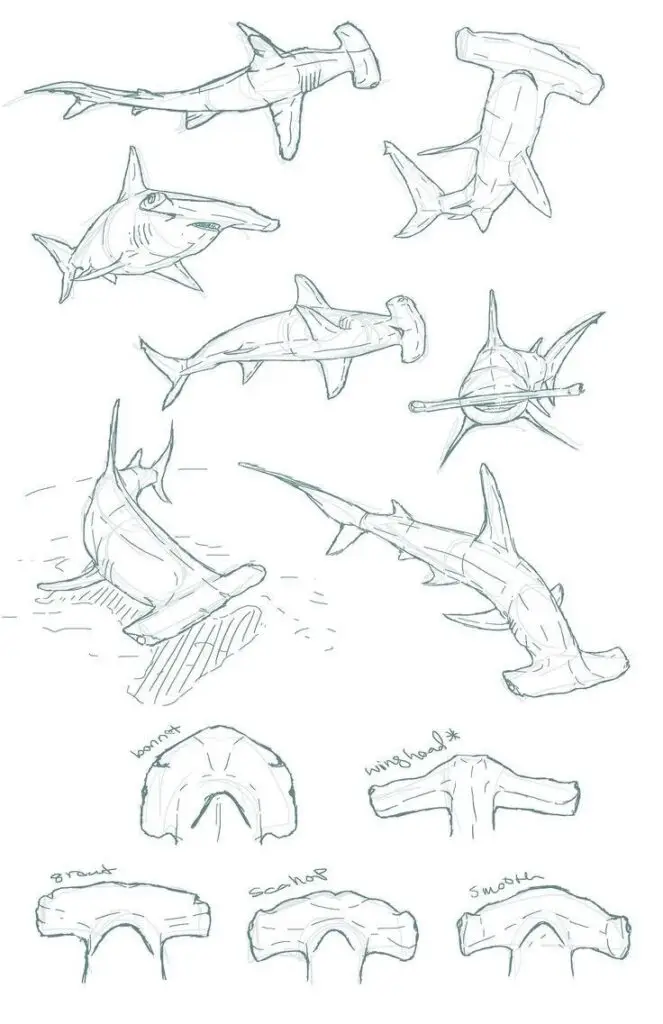

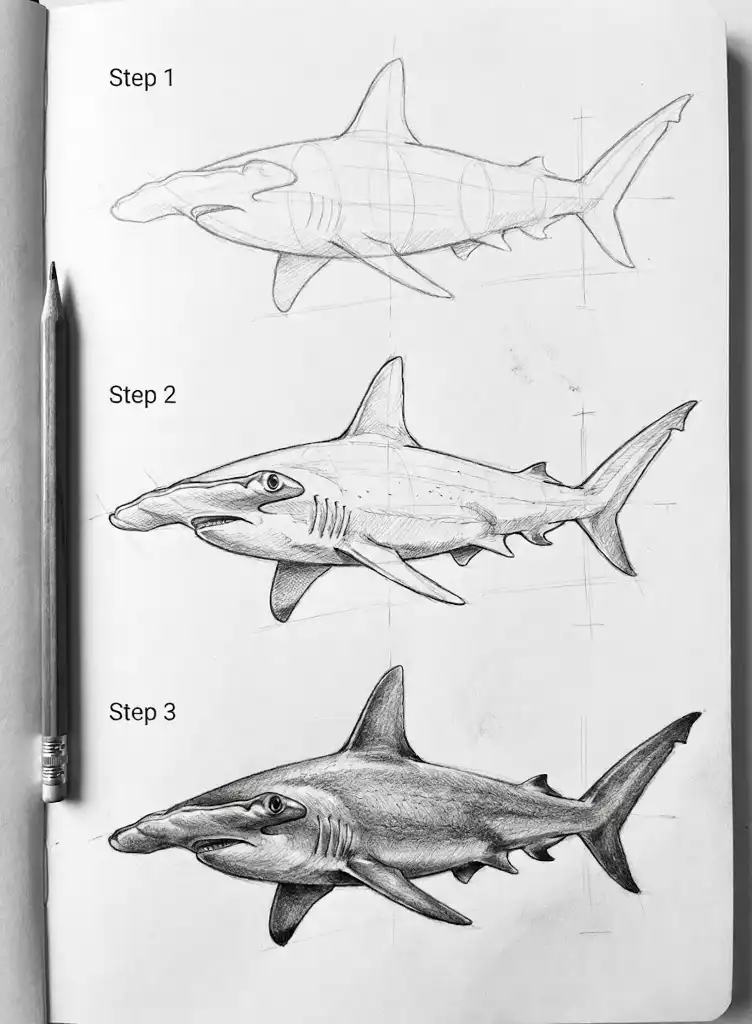

Hammerhead Shark

Impossible to misidentify thanks to that distinctive head shape.

Key features:

- Cephalofoil (hammer-shaped head) varies by species: T-shaped in great hammerhead, rounded with central notch in scalloped hammerhead

- Eyes positioned at the outer edges of the hammer

- More slender body than great white

- Tall, curved first dorsal fin

- Gray-brown coloring, lighter underneath

Artist’s tip: The hammer isn’t flat—it has depth. Draw it as a 3D form, not a 2D cutout. The underside of the hammer is particularly important in three-quarter views.

Cultural note: In Torres Strait Islander culture, the hammerhead (beizam) represents law and order. Artist Ken Thaiday Snr creates stunning sculptural representations of hammerheads in traditional headdresses called dhari.

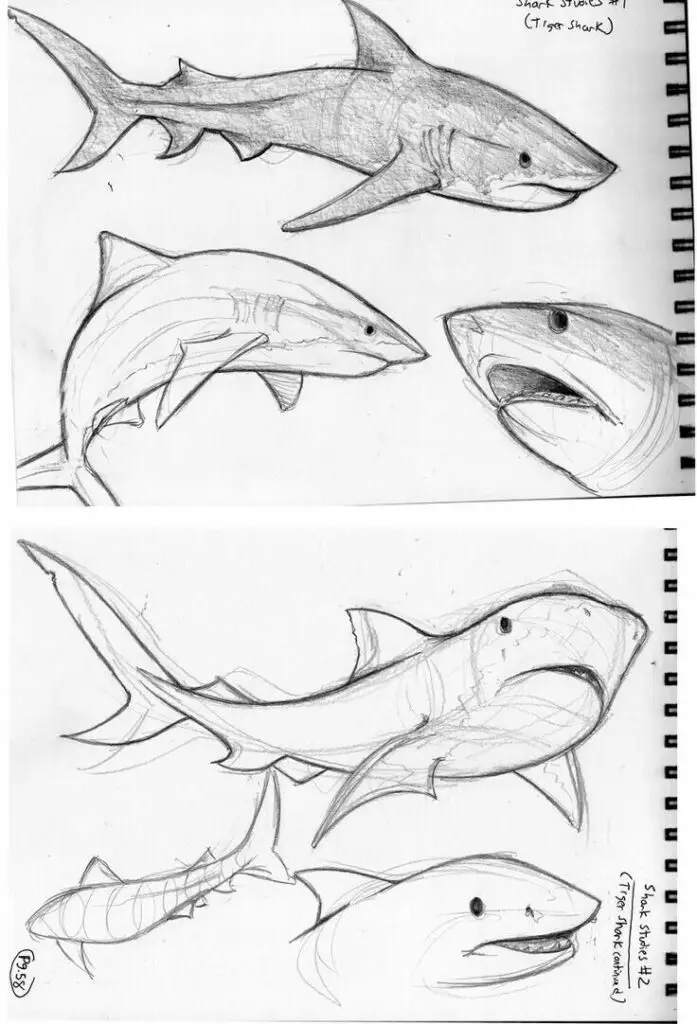

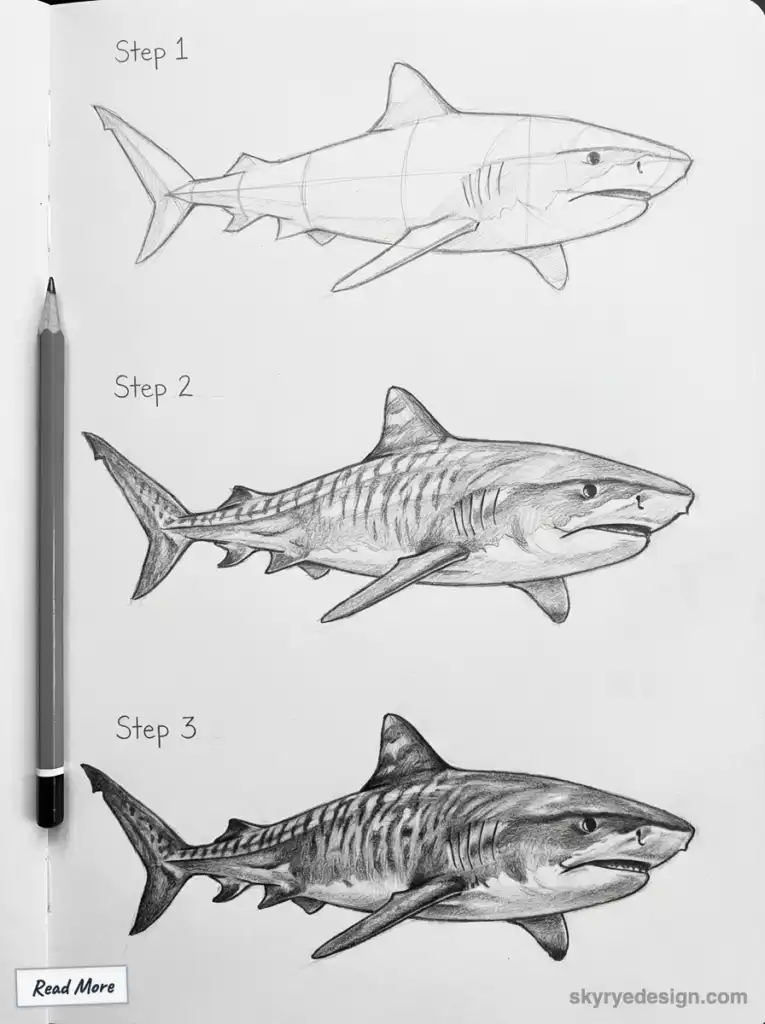

Tiger Shark

Named for the dark stripes along its body (more visible in juveniles).

Key features:

- Blunt, rounded snout

- Very large mouth relative to head size

- Vertical stripes/bars that fade with age

- Broad, flat head when viewed from above

- Distinctive notched upper tail lobe

Artist’s tip: Tiger sharks are scavengers with massive mouths. Emphasize that gaping jaw—it’s their defining feature after the stripes.

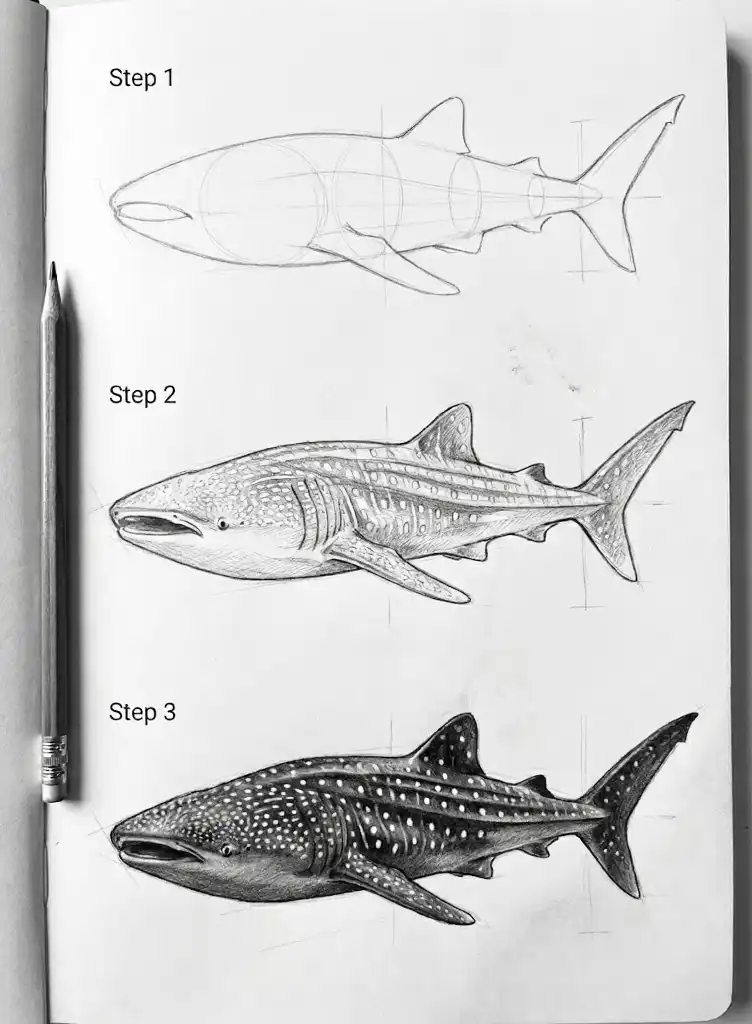

Whale Shark

The gentle giant. Largest fish in the ocean at up to 62 feet.

Key features:

- Flat, squared-off head with mouth at the front (not underslung)

- Distinctive checkerboard pattern of white spots and stripes on dark background

- Extremely wide body

- Small eyes relative to massive head

- Three prominent ridges along each side of the body

Artist’s tip: The whale shark’s pattern is its signature. Take time to suggest the spots and stripes—even a few well-placed marks communicate “whale shark” instantly.

Mako Shark

The speed demon—fastest shark in the ocean at up to 46 mph.

Key features:

- Extremely streamlined, torpedo-shaped body

- Long, pointed snout

- Large, visible teeth even when mouth closed

- Bright blue coloring on top (often called “shortfin mako blue”)

- Crescent-shaped tail with nearly equal lobes

Artist’s tip: Everything about the mako says “speed.” Use long, flowing lines and an aggressive forward lean to capture this.

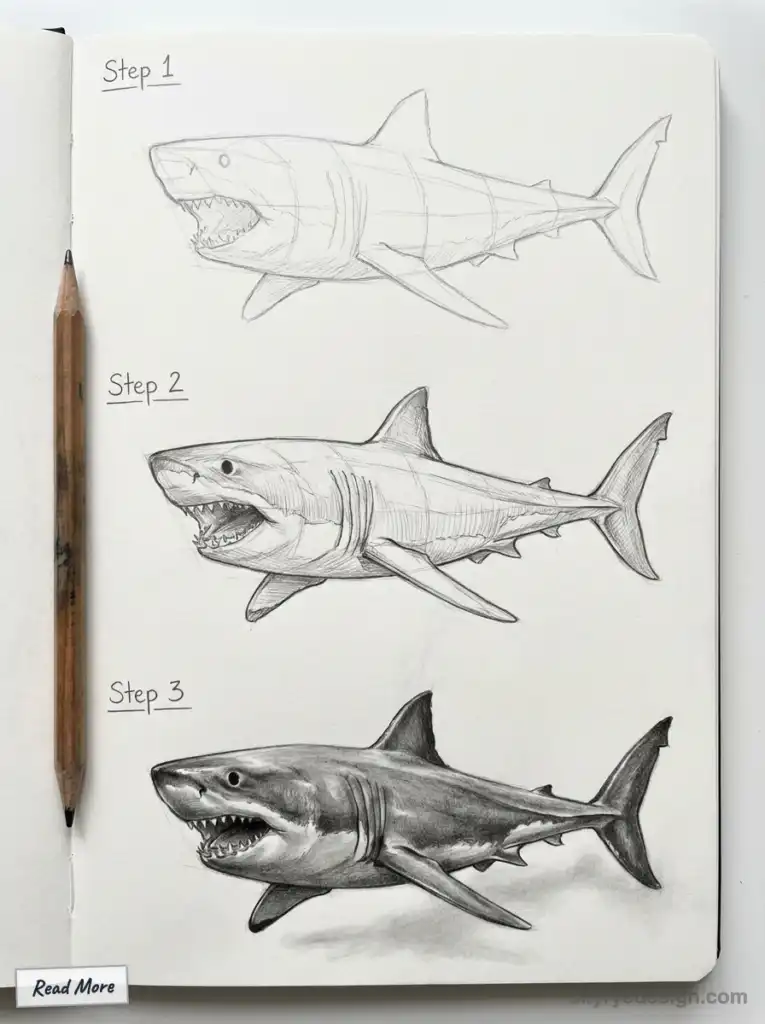

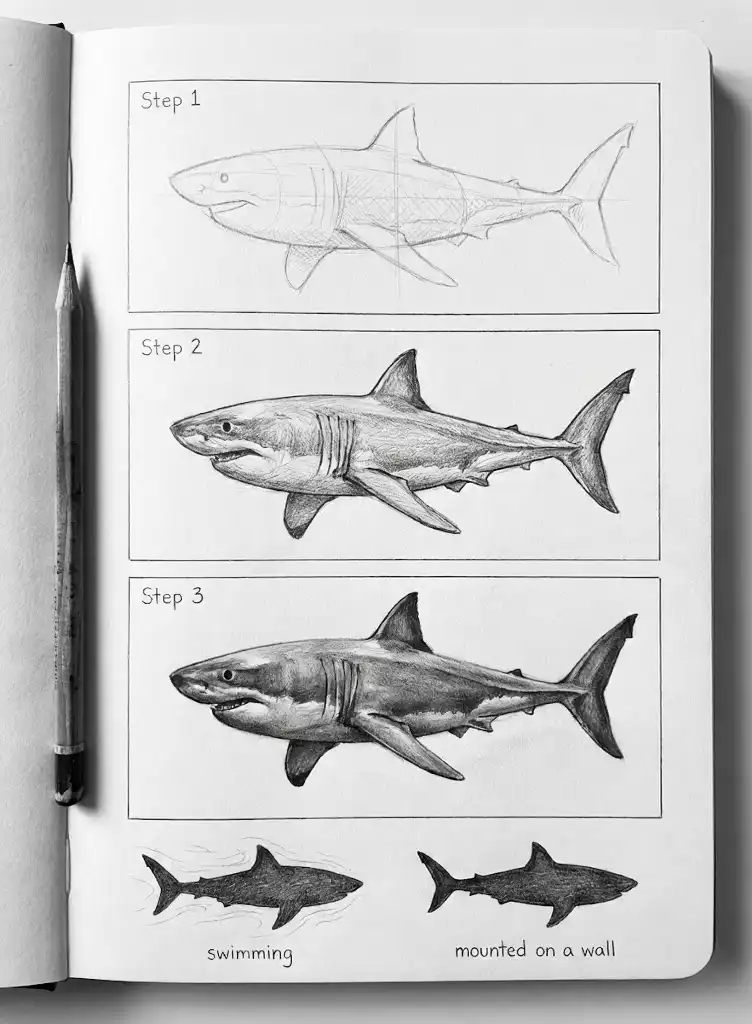

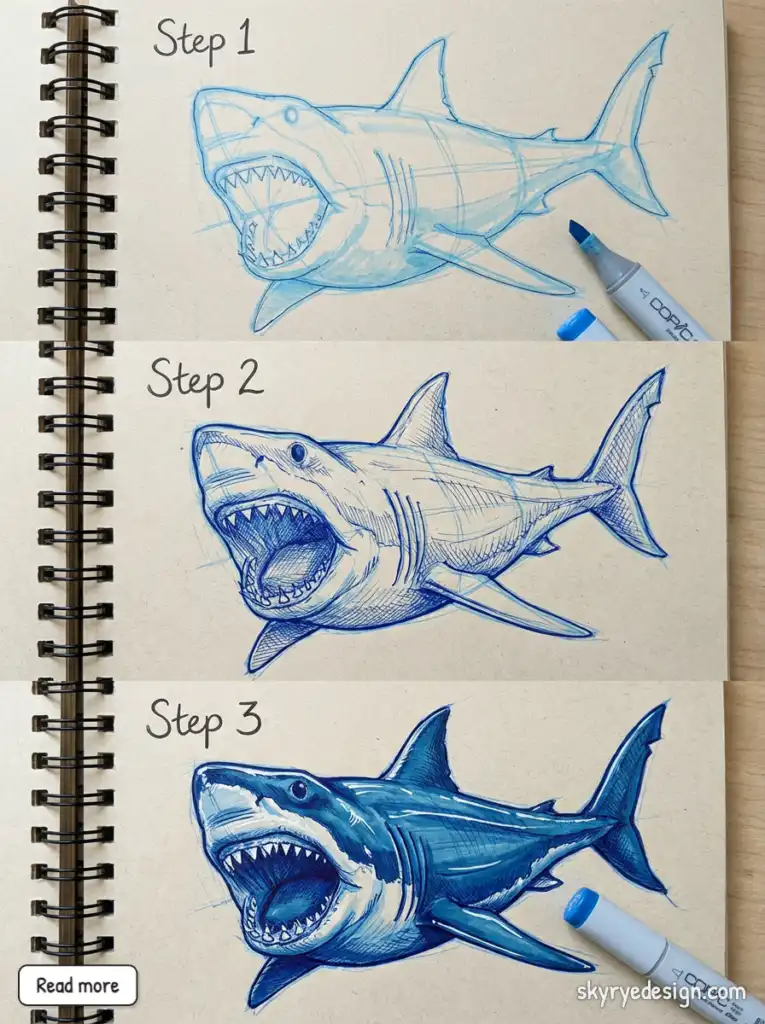

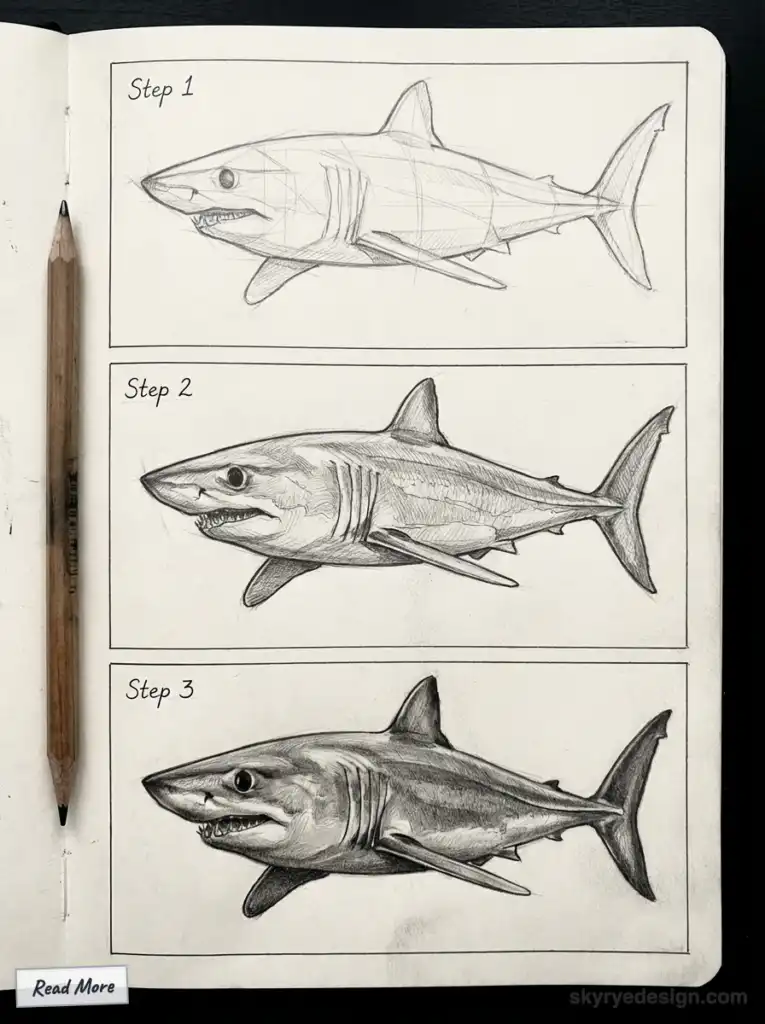

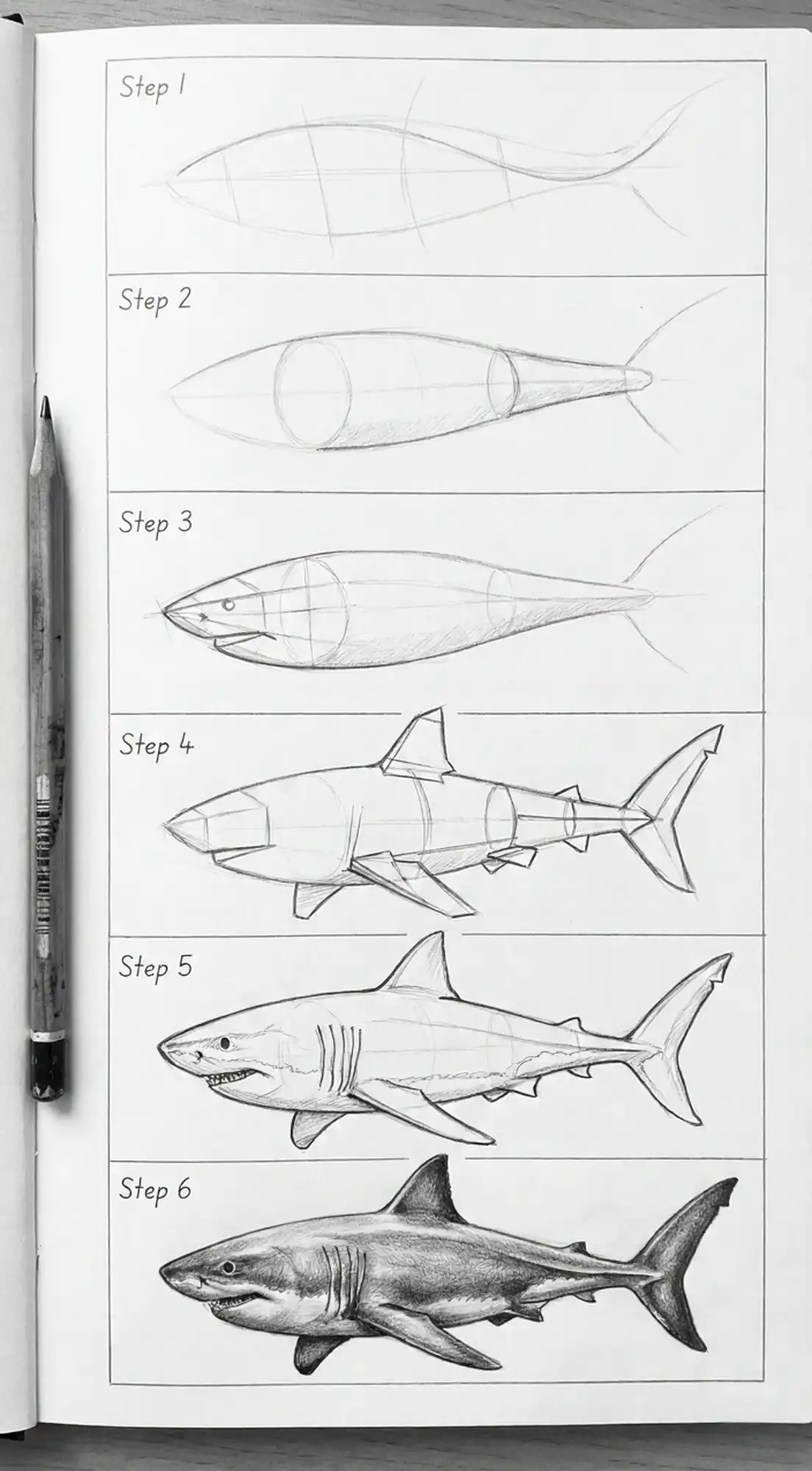

Step-by-Step: Basic Shark Drawing Method

This method works for any species. Adjust proportions for your target shark.

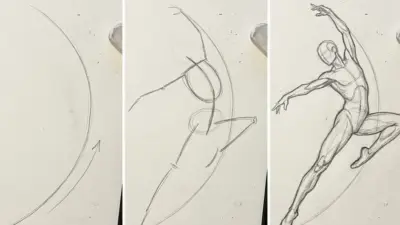

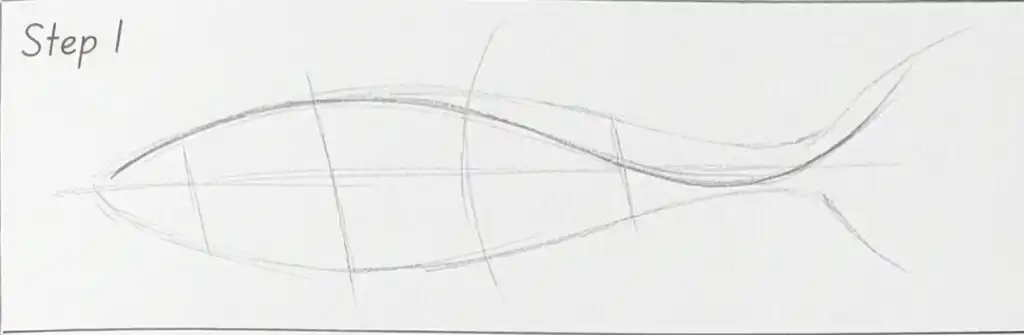

Step 1: The Gesture Line (10 seconds)

Draw a single curved line representing the shark’s spine and direction of movement. This is your foundation. A straight line = static shark. A curved line = dynamic shark.

The curve should follow the motion: an S-curve for turning, a gentle arc for cruising, a tight curve for attacking.

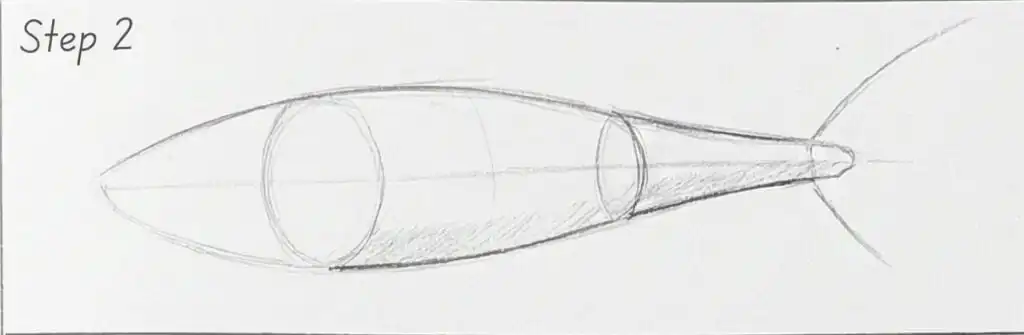

Step 2: The Body Mass (30 seconds)

Build a tapered oval around your gesture line. Thicker in the middle, narrowing toward both ends. Don’t worry about being precise—you’re establishing volume, not detail.

Proportions for a great white:

- Head = roughly 1/5 of total length

- Body (thickest part) = middle 2/5

- Tail section = remaining 2/5

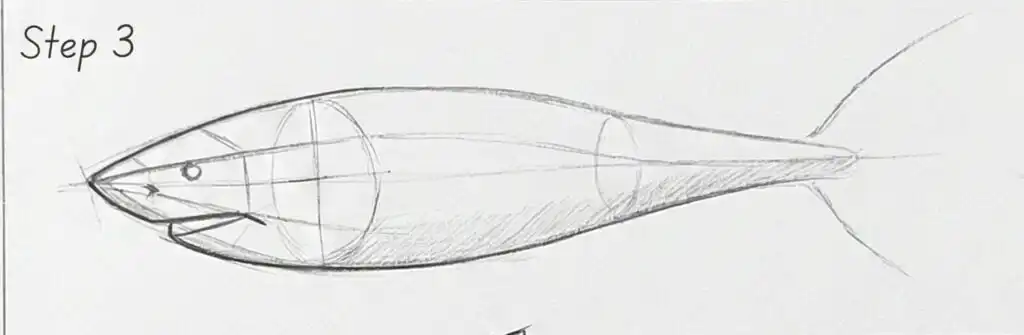

Step 3: The Head Shape (20 seconds)

Refine the front of your oval into the snout. Different species = different shapes:

- Great white: pointed cone

- Tiger: rounded, blunt

- Hammerhead: add the cephalofoil perpendicular to the body

- Whale shark: flatten and widen

Add a horizontal line across the head for eye placement. For most species, this line sits at the widest part of the head.

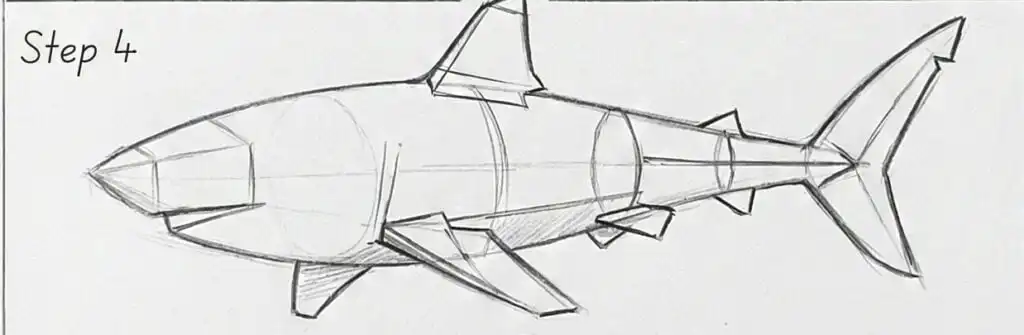

Step 4: Fin Placement (30 seconds)

Add fins as simple shapes first:

- Dorsal fin: triangle at the highest point of the body

- Pectoral fins: angled triangles below and behind the gills

- Pelvic fins: smaller triangles behind pectorals

- Anal fin: small triangle on underside

- Caudal fin: crescent shape at the tail

Remember: Fin angles communicate movement. All fins swept back = speed. Fins extended = cruising or maneuvering.

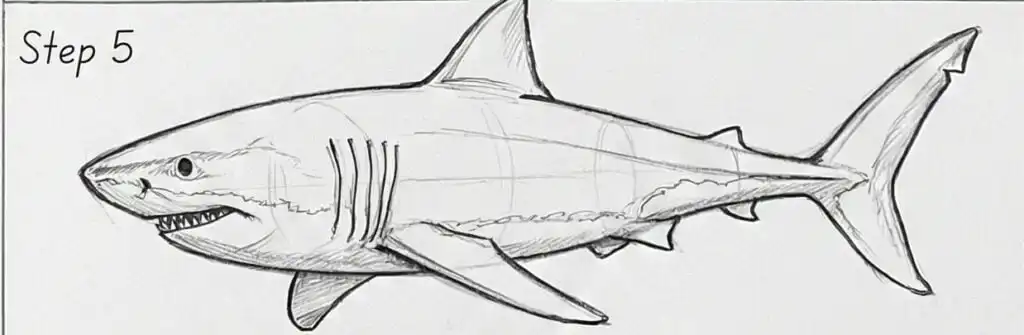

Step 5: Details (2-3 minutes)

Now add:

- Eye (on that horizontal line you drew earlier)

- Gill slits (5-7 vertical lines behind the eye)

- Mouth line (curved, underslung)

- Refine fin shapes with curves rather than straight edges

- Add secondary dorsal fin (smaller, further back)

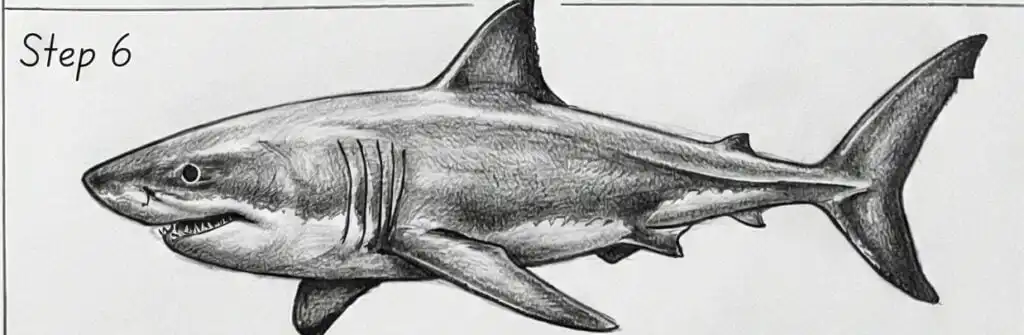

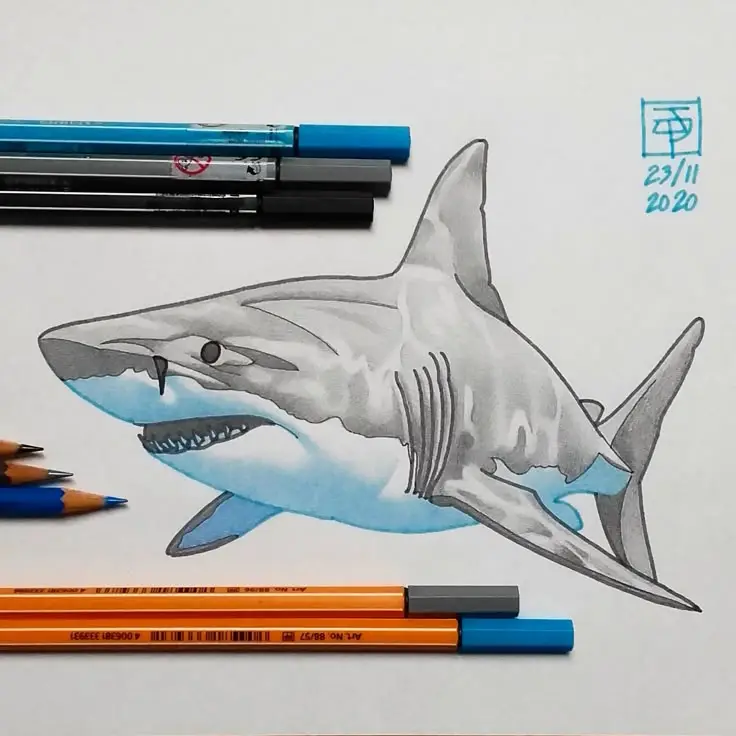

Step 6: Shading and Texture (varies)

Basic shading rules for sharks:

- Darkest on top (back)

- Lightest on bottom (belly)

- Gradient transition on the sides

- Fins slightly darker than body

- Highlight on the snout and dorsal fin

For texture, suggest rather than draw every detail. A few curved lines along the body imply the direction of dermal denticles (shark “scales”). Rows of dots near the snout suggest the ampullae of Lorenzini (electroreceptors).

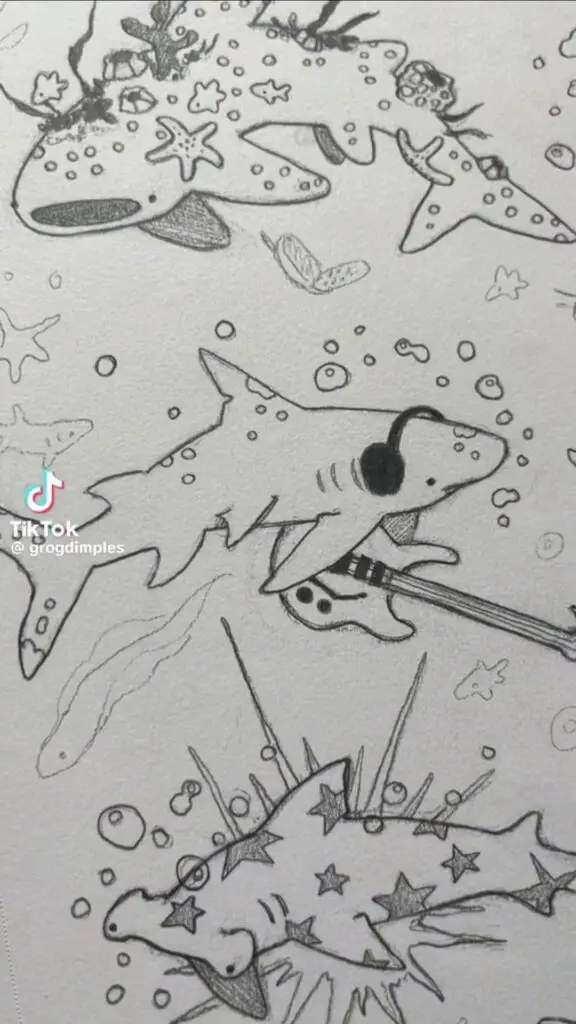

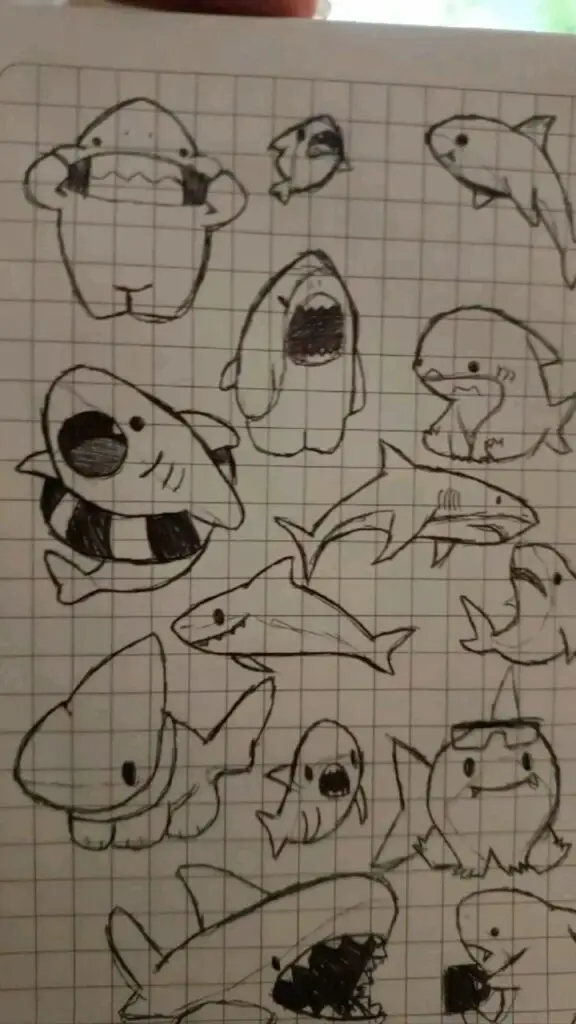

Style Variations for Shark Drawings

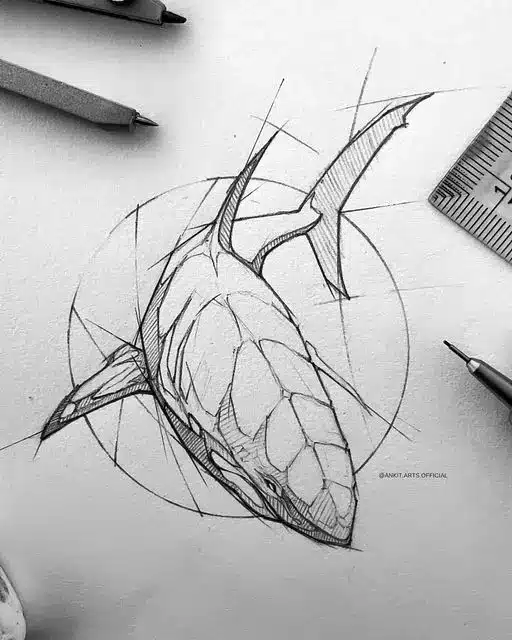

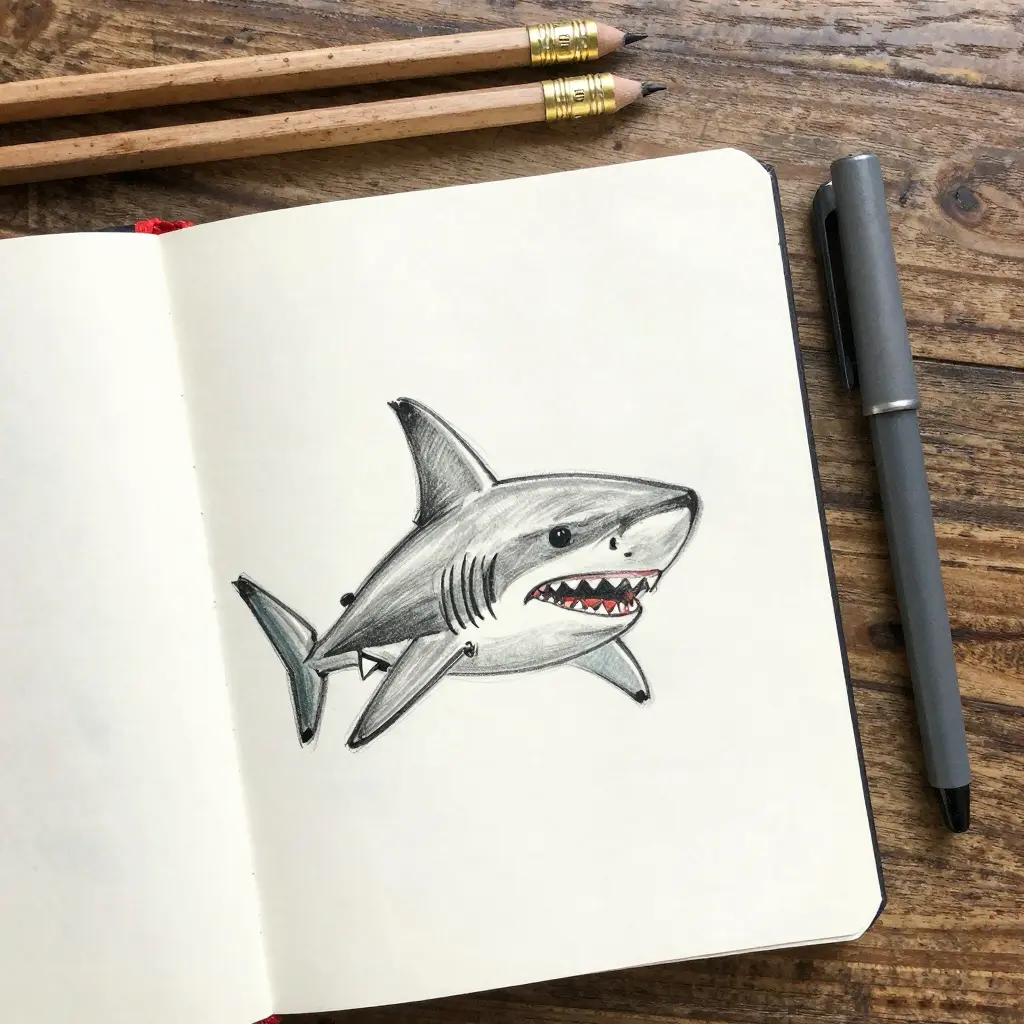

Realistic/Scientific

Focus on accurate proportions and anatomical detail. Study reference photos extensively. Use subtle value gradations and precise line work.

Best for: Educational materials, scientific illustration, portfolio pieces

Tools: Graphite pencils (2H-6B range), blending stumps, reference images

Time investment: 3-10+ hours per drawing

Artists to study: Aaron Blaise, Mark Carwardine’s wildlife guides

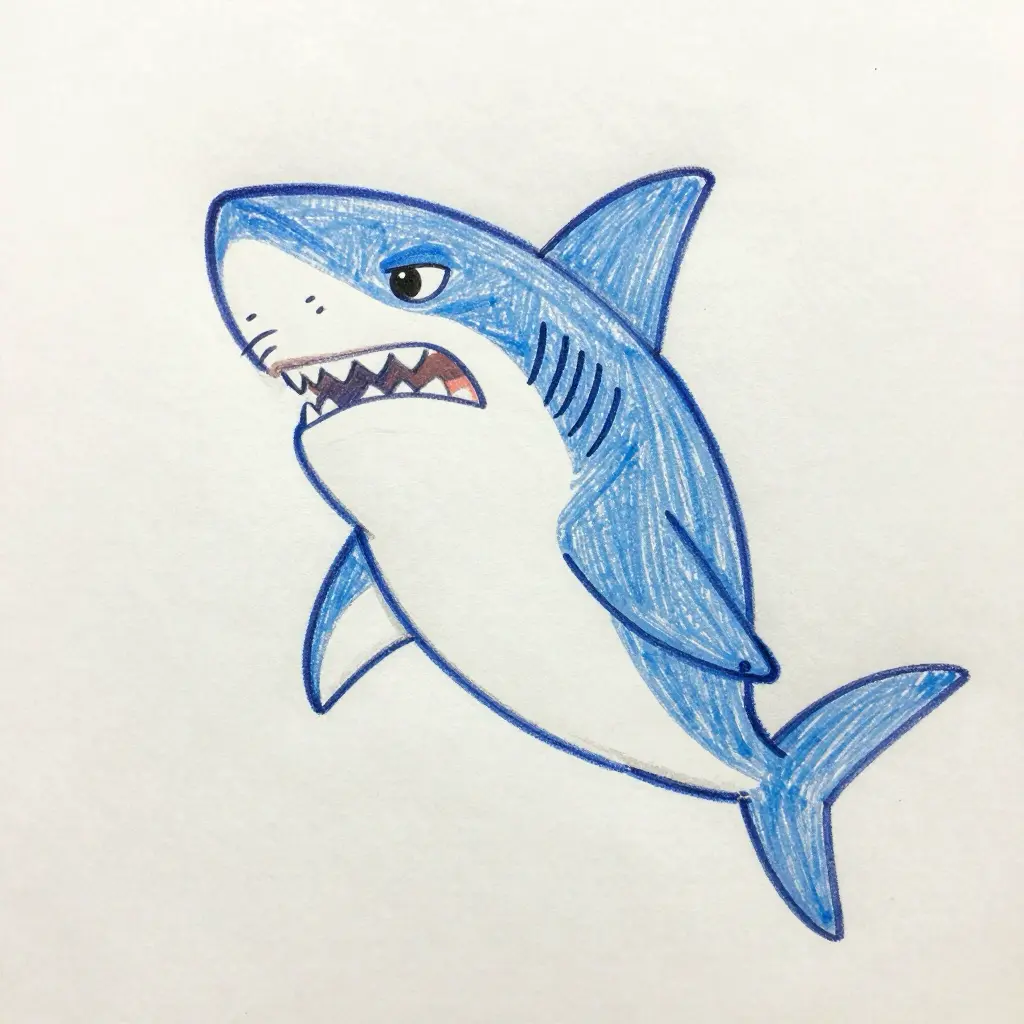

Cartoon/Character Design

Exaggerate distinctive features. Simplify shapes. Add personality through expression.

Best for: Children’s books, animation, merchandise, social media

Tools: Markers, digital drawing tablets, bold colors

Key adjustments:

- Larger eyes (move toward front of head for “friendly”)

- Simplified fin shapes

- Exaggerated teeth for menacing, hidden teeth for friendly

- Rounder body for cute, angular for villainous

Traditional Tattoo Style

Bold outlines, limited color palette, stylized forms. Think Sailor Jerry meets marine biology.

Best for: Tattoo flash, bold graphic design, vintage aesthetics

Key elements:

- Thick, consistent outlines

- Limited shading (usually just solid fills)

- Classic color palette: navy, teal, red, gold

- Often shown in aggressive pose with open mouth

Minimalist/Line Art

Single-weight lines, no shading, essential forms only.

Best for: Logos, modern design, quick sketches, social media icons

Challenge: Communicating “shark” with the fewest possible lines. The silhouette does all the work.

Watercolor

Soft edges, color bleeding, luminous quality that suggests underwater environment.

Best for: Fine art, greeting cards, children’s books

Technique tips:

- Wet-on-wet for the body (soft edges)

- Wet-on-dry for details like eye and gill slits

- Let white paper show through for highlights

- Layer blues and grays for depth

Common Mistakes in Shark Drawings (And How to Fix Them)

Mistake 1: Symmetrical Poses

The problem: Drawing sharks perfectly straight-on, both sides identical. Looks stiff and artificial.

The fix: Always include some asymmetry. One pectoral fin angled differently than the other. Body slightly curved. Tail pushing in one direction.

Mistake 2: Wrong Fin Proportions

The problem: Dorsal fin too large (the “Jaws poster syndrome”) or pectoral fins too small.

The fix: Use references. In most sharks, the pectoral fins are actually larger than the first dorsal fin. The Jaws poster exaggerated for dramatic effect—that’s movie magic, not biology.

Mistake 3: Human Eye Placement

The problem: Drawing shark eyes facing forward like a human. Sharks have eyes on the sides of their heads.

The fix: In a side view, you should only see one eye. In a three-quarter view, the far eye is barely visible or hidden by the snout.

Mistake 4: Static Tail

The problem: Tail drawn as a stiff, symmetrical shape.

The fix: The tail is always mid-stroke. Curve it. Show the direction of thrust. The upper and lower lobes should rarely be mirror images.

Mistake 5: Ignoring the Environment

The problem: Shark floating in white void.

The fix: Add environmental cues—even subtle ones. Light rays from above. A hint of ocean floor below. Bubbles near the gills. Water affects how we read the image.

Materials for Shark Drawings

For Beginners

- Sketchbook: Any 80+ GSM paper works for practice

- Pencils: One HB and one 4B covers most needs

- Eraser: Kneaded eraser for lifting, white eraser for clean removal

- Reference photos: Tattoodo, Adobe Stock, or nature documentaries paused

Budget: Under $20 gets you started

For Intermediate Artists

- Paper: Bristol board (smooth) for detailed work, mixed media paper for experiments

- Pencils: Full graphite range (2H-8B) or mechanical pencils with varying leads

- Blending tools: Stumps, tortillons, tissue paper

- Inking: Micron pens (0.1, 0.3, 0.5) for linework

Budget: $40-80 for a solid kit

For Digital Artists

- Hardware: Drawing tablet (Wacom Intuos at entry level, Cintiq or iPad Pro for serious work)

- Software: Procreate (iPad), Clip Studio Paint (all platforms), Photoshop

- Brushes: Look for natural pencil and ink brushes; Kyle Webster’s brushes for Photoshop are industry standard

Budget: $300+ for tablet, $0-50 for software

For Watercolor

- Paper: 140 lb cold press minimum (hot press for detailed work)

- Paints: Student grade is fine for practice; Winsor & Newton Cotman is good value

- Brushes: Round brushes in sizes 2, 6, and 10 cover most needs

- Essential colors: Payne’s grey, ultramarine blue, burnt sienna, Prussian blue

Budget: $50-100 for a starter kit

Sharing Your Shark Drawings

Best Platforms by Style

Instagram: All styles work here. Use hashtags like #sharkdrawing, #sharksofinstagram, #marineart, #wildlifeart. Reels showing your process perform well.

Pinterest: Gallery-style posts with multiple views of the same shark. Surprisingly strong engagement for marine art. Good for driving traffic to portfolios.

DeviantArt: Still active for wildlife and fantasy art. Good for detailed, realistic work and getting feedback from other artists.

Tattoodo: If you’re creating tattoo-style sharks, this is where potential clients and collaborators look.

Selling Your Work

Print-on-demand: Redbubble, Society6, and TeePublic let you sell shark designs on products without inventory. Margin is low, but it’s passive income.

Stock illustration: Submit vector shark designs to Shutterstock, Adobe Stock, or iStock. Scientific/educational styles sell consistently.

Commissions: Build a portfolio first, then offer custom shark drawings. Pricing typically starts at $50-100 for digital work, higher for traditional media.

Original art: Etsy and Instagram are primary channels for selling original drawings. Frame and present professionally. Signed, limited-edition prints can work as a middle price point.

Frequently Asked Questions

What’s the easiest shark to draw for beginners?

The great white is actually a good starting point because its proportions are well-documented and its shape is what most people picture when they think “shark.” The whale shark is also beginner-friendly because its blocky head is more forgiving of proportion errors.

Avoid starting with hammerheads—that cephalofoil is deceptively difficult to draw convincingly in three dimensions.

How do I make my shark look like it’s actually swimming?

Three things: gesture line (curved, not straight), fin angles (asymmetrical, suggesting movement direction), and implied water (subtle shading gradients, trailing motion lines). A shark in motion is never perfectly symmetrical.

What references should I use?

Nature documentaries on pause are gold—you get real-world lighting and movement frozen. Our Planet and Blue Planet on Netflix have excellent shark footage. For still images, the NOAA Fisheries shark identification guides have accurate anatomical reference. Avoid heavily edited photos that exaggerate features.

Can I draw cartoon sharks without learning realistic anatomy?

You can, but your cartoon sharks will be better if you understand the underlying structure first. Even the most stylized characters (like Bruce from Finding Nemo) are built on solid anatomical foundations. Learn the rules, then break them intentionally.

How long does it take to get good at drawing sharks?

Depends on your definition of “good” and how much you practice. Most artists see noticeable improvement after 20-30 focused drawings of the same subject. If you’re serious about shark drawings specifically, commit to one shark sketch per day for a month. You’ll be surprised at the progress.

What’s the most common mistake professional artists see in beginner shark drawings?

Stiff poses and wrong fin proportions. Both come from drawing from imagination rather than reference. Even experienced artists use references—there’s no shame in it. The goal isn’t to memorize what a shark looks like; it’s to understand how it moves and how light interacts with its form.

Your Next Steps

You’ve got the anatomy breakdown, the species guide, and the technique overview. Now it’s about putting pencil to paper.

Start here:

1. Pick one species. Don’t try to master all sharks at once. Great white is a solid choice—well-documented and instantly recognizable.

2. Gather 10+ reference images. Different angles, different lighting, different poses. Create a reference folder you can access while drawing.

3. Do 10 gesture sketches. One minute each, no details. Just the movement line and basic body mass. This builds muscle memory for the form.

4. Complete one finished drawing. Take your best gesture, develop it fully using the step-by-step method above. Don’t rush.

5. Post it somewhere. Instagram, DeviantArt, Reddit’s r/learnart—wherever. Getting feedback accelerates improvement.

I’ve noticed the artists who improve fastest are the ones who draw consistently, not the ones who wait for inspiration. A mediocre shark drawing done today beats a perfect shark drawing that never happens.

The ocean has over 500 shark species. That’s 500 different body plans, 500 different fin arrangements, 500 different expressions to capture. You’re not going to run out of subjects.

Pick up the pencil. Draw a predator.

- 4.5Kshares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest4.5K

- Twitter3

- Reddit0