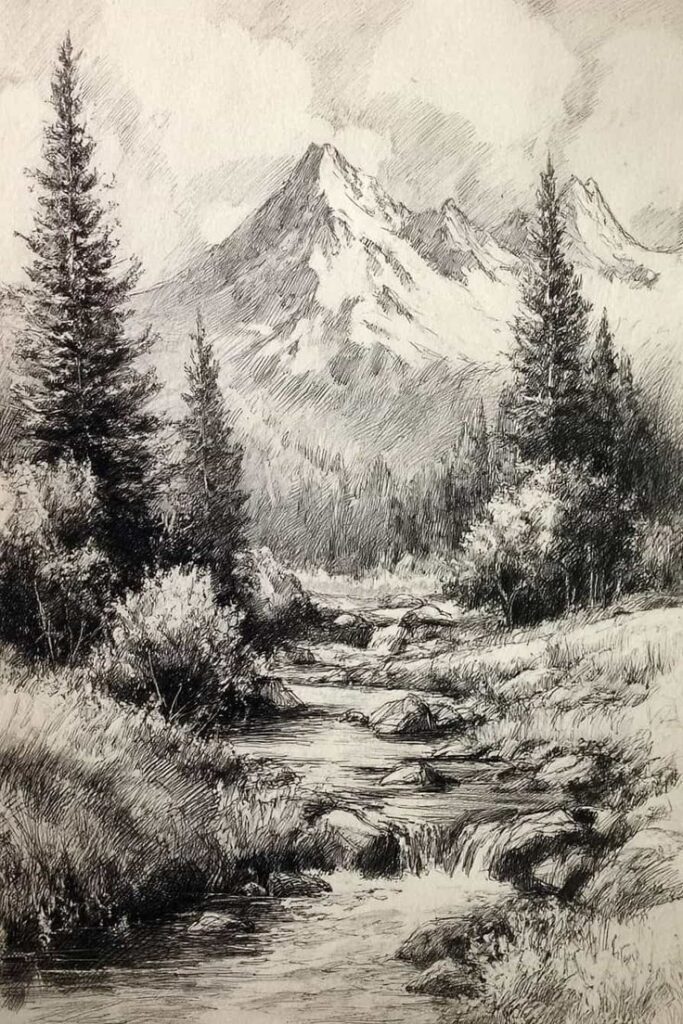

Discover landscape architecture sketches

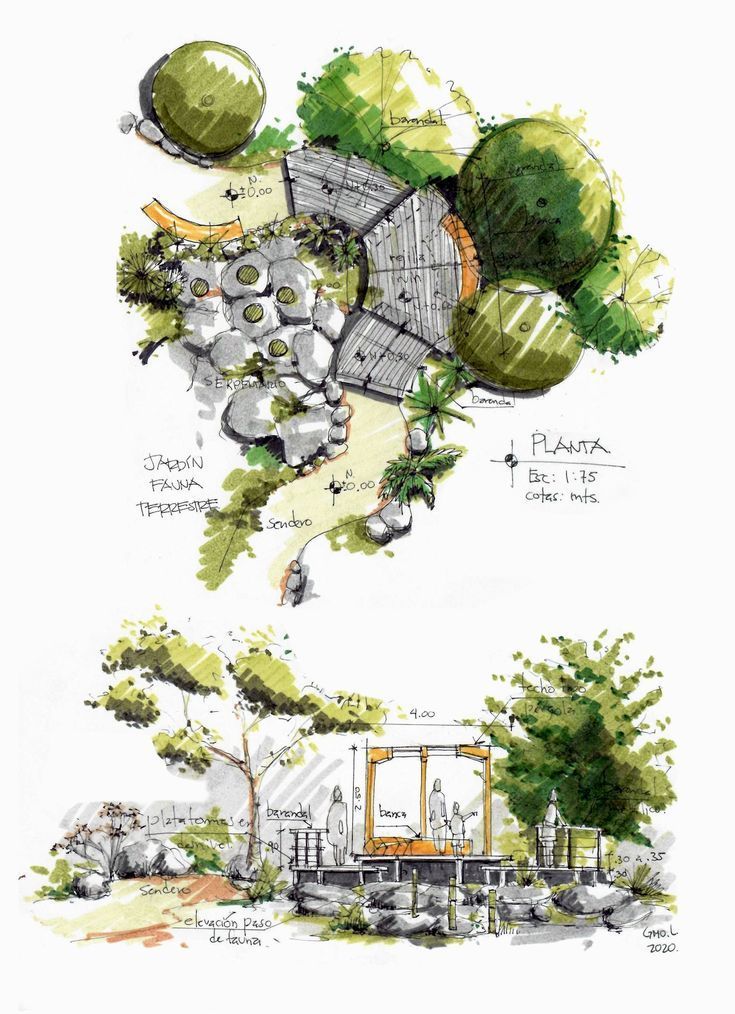

Landscape architecture sketches offer more than just lines on paper. They reveal how designers interpret open spaces, translate natural elements into shapes, and envision environments that blend functionality with beauty. From the meandering water features at an urban park to the slope of a hillside garden, these sketches capture the soul of a site long before cranes or excavators arrive. Whether the project is a small courtyard in a suburban enclave or an expansive city masterplan, sketching remains a vital step that helps designers communicate ideas quickly and clearly.

Landscape professionals have relied on sketching for centuries. Hideo Sasaki, Capability Brown, and Frederick Law Olmsted all used sketches to translate fleeting thoughts into tangible proposals that could be shared with clients and communities. Modern digital tools certainly add precision, but traditional sketches still shine, as believed by Sasaki Associates in 2025: drawing by hand sparks creativity, fosters a deeper sensory link, and invites faster exploration of spatial possibilities (Sasaki). These landscape architecture sketches become the first visual handshake between designer and environment.

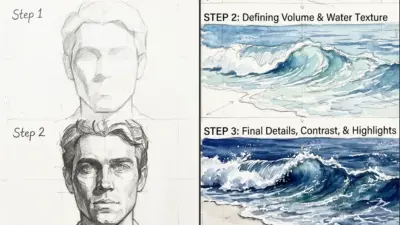

Below is a practical tutorial on how practitioners approach hand-drawn techniques. Each step moves from laying the foundation of observation to combining sketches with technology. By the end, an aspiring or seasoned designer can refine a workflow that liberates ideas, encourages collaboration, and sets the stage for spectacular outdoor spaces.

Understand why sketching matters

Sketching in landscape architecture is not just a relic of the past. According to Sasaki Associates, it remains irreplaceable in modern workflows because it fuses quick thinking, systems exploration, and artistic expression in ways computers rarely replicate (Sasaki). In a single pencil stroke, the designer can test a water feature’s scale, tweak planting arrangements, or imagine new pathways that frame scenic views.

It promotes bigger-picture thinking

Designers must often consider how a plaza integrates with fountains, seating, irrigation networks, and biodiversity. Sketches allow for a swift layering of these factors to see if they harmonize. By capturing multiple elements at once, the designer can spot disruptions early.It stimulates creative flow

The act of moving graphite or ink on paper releases the mind from perfectionism. Rough shapes will do initially, followed by broader strokes that conjure up new perspectives. Sasaki Associates points out that such spontaneity is essential for systems thinking and iterative design, especially in complex settings like a multi-acre city park.It offers tactile feedback

Landscape architects engage a feedback loop between hand, mind, and environment. Textures, slopes, and shadow lines become clearer when physically drawn. In the words of Richard E. Scott, hand sketches sharpen the ability to see and think critically, enhancing how designers shape a project’s vision (Land8).It connects people

During client meetings, a sketch can do more than a digital model. Clients respond to these drawings with enthusiasm and curiosity, as they sense the designer’s thought process. They can see rough lines evolving into ideas. That sparks conversation and makes them feel part of the creative journey.

Practice foundational techniques

A blank page can feel both exhilarating and daunting. Yet the best way to tame uncertainty and develop skill is consistent practice. Draftscapes offers several tried-and-tested exercises—activities that build confidence and technique step by step (Draftscapes). By focusing on a few core exercises, practitioners can accelerate their growth immensely.

The Timed Sketch

Timed sketching teaches designers to capture the essential elements of a scene quickly. The exercise typically involves:

Selecting five landscape photos

These could be images of gardens, parks, or sweeping horizon lines. Each photo should provide a clear sense of depth and composition.Setting decreasing time limits

Designers might start with five minutes for the first sketch, then four minutes for the second, three for the third, and so forth until only one minute is allowed. This time restriction forces them to block out the main features without fussing over details.Distilling the essential forms

With limited time, the designer must compress an entire view into a few strokes. Trees may become scribbled cones; water features might appear as broad shapes. Over time, participants learn to quickly decode what is most important in a scene—pathways, focal points, or major vegetation masses.

This drill is ideal for training the designer’s eye to find anchors within any environment. By the end, the page might look simplified, but that stripped-down representation can guide a robust final design.

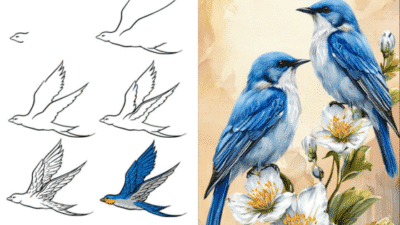

100 Leaves

In this activity, the designer draws the same leaf shape 100 times in various orientations. This repetition builds muscle memory and challenges the artist to see nuances that might otherwise go unnoticed. Each variation refines how lines describe contours, veins, and folds.

- Start with a real leaf

Observing a leaf from life improves accuracy. Notice how it curves or how the main vein connects to side veins. - Vary the angle

After a few sketches, rotate the leaf or shift positions to capture a different perspective. - Focus on shapes, not symbols

Rather than drawing a stylized leaf symbol, designers aim to capture the Leaf’s unique silhouette—large or small, round or elongated.

After 100 sketches, the hand moves more intuitively, and the eye better grasps subtleties in organic forms. This attention to detail eventually translates into more balanced and coherent designs.

The Daily Diary

A small, consistent practice can produce huge gains. Draftscapes suggests dedicating just five minutes a day to scribble landscapes, objects, or fleeting moments, whether it is sketching a row of hedges during a walk or capturing the silhouettes of distant hills (Draftscapes).

- Keep it casual

The goal is not to produce masterpiece drawings, but to keep the pencil moving. - Anchor with a simple routine

Some do it during their morning coffee, while others sketch right before bed. - Track progress in a sketchbook

Each page becomes a visual diary of a designer’s evolving skill set.

With these three exercises, novices and professionals alike can train their eyes, hands, and minds to see patterns and shapes more accurately.

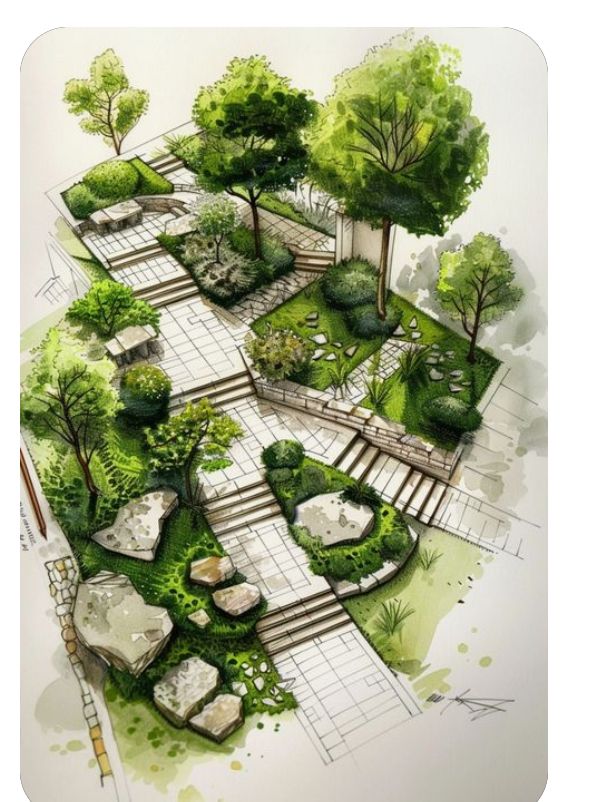

Combine traditional and digital tools

Modern technology provides clarity that can be difficult to achieve through freehand sketches alone. Tools such as GIS mapping, 3D modeling software, and advanced rendering programs are commonplace in design offices. However, Sasaki Associates cautions that these technologies do not replace the need for hand sketches—they complement them (Sasaki).

Start with a hand drawing

Early in the design, many professionals begin with a pencil or pen to flesh out broad ideas. This is the phase when creativity should flow most freely.Transition to digital refinement

Once a concept feels promising, the designer can scan the sketch or recreate it in CAD software. Here, they can adjust measurements and examine structural feasibility. A swirl of color-coded lines might represent water drainage, topography, or pathways.Use overlays

Combining manual sketches with transparent layers or digital overlays reveals how the design evolves from rough concept to final plan. A rough pencil outline can still be seen beneath precise digital lines, highlighting the creative journey for clients.Reflect on the synergy

Integrating analog with digital helps maintain an organic spark. Designers often feel that pure digital modeling can lose the warmth of intuitive thinking. By layering technology over freehand sketches, they harness the best of both worlds.

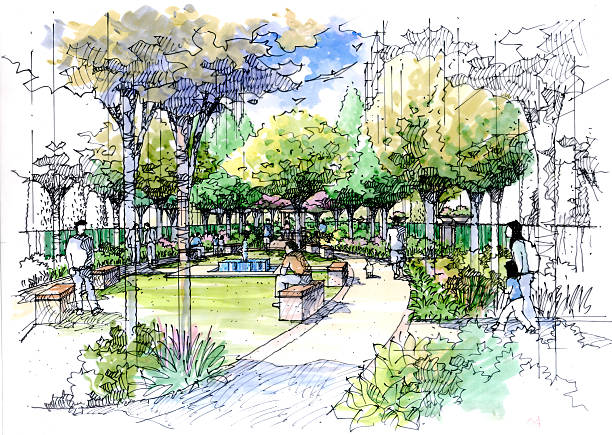

Present and refine sketches collaboratively

Landscape architecture sketches do more than illustrate solitary ideas; they bring multiple voices into the design process. According to Richard E. Scott, live sketching in a meeting can shift the atmosphere, making it more informal and interactive (Land8). As team members watch lines form on the page—perhaps a meadow here or a line of birch trees there—they can chime in with comments, suggestions, or applause.

Use sketches for storytelling

People relate to stories, and sketches can speak volumes without a single word. In the tradition of capability Brown and Frederick Law Olmsted, drawing a pastoral scene or meandering footpath invites onlookers to imagine the final environment. They see themselves strolling through tall grasses or resting on a bench near a reflecting pool. Through hand-drawn representation, the design narrative becomes clear, direct, and compelling.

Iterate through feedback loops

During critique sessions or design charrettes, sketches can be taped to walls or pinned onto digital boards. If a colleague points out that the rain garden might work better at the lowest point of the site, the designer can quickly adjust lines right there. This real-time editing fosters collaboration, ensuring that the final design speaks to multiple perspectives—from ecologists to city planners.

Spark deeper connections

In many studios, group sketch sessions can surface synergy that might be lost when everyone is fixated on separate computer screens. The quick, intuitive nature of hand drawing fosters trust, transparency, and genuine creativity. It reduces the distance between professional expertise and fresh ideas from community members who might have no design background but can comment intuitively on a quick sketch.

Look to inspiring masters

Today’s designers stand on the shoulders of giants. From 17th-century visionaries to contemporary practitioners, sketches have always illuminated a landscape architect’s approach. Consider these icons for insights on technique:

André Le Nôtre (1613-1700)

This French landscape architect shaped the breathtaking gardens of Vaux-le-Vicomte and Versailles (Land8). His sketches revealed an incredible understanding of geometry and axial symmetry that still inspires symmetrical garden designs.Lancelot “Capability” Brown (1716-1783)

Known for the naturalistic style of gently rolling lawns and serpentine lakes, Brown’s drawings often showed arcs of water and tree clusters that shaped over 170 gardens, including Kew Gardens (Land8). They may seem simple, but those arcs convey a surprisingly measured sense of balance.Gertrude Jekyll (1843-1932)

Famous as one of the first renowned women in landscape architecture, Jekyll integrated proportion, color balance, texture, and fragrance in her gardens. Her sketches reveal a layered understanding of horticulture—every plant has a purpose, and each part of the sketch suggests a deliberate color scheme (Land8).Frederick Law Olmsted (1822-1903)

Widely hailed as the father of American landscape architecture, Olmsted’s conceptual drawings of Central Park shaped an entire discipline. Much like Brown, Olmsted’s sketches often disguised rigorous planning behind apparently effortless curves and vistas.Roberto Burle Marx (1909-1994)

A modern master from Brazil, Burle Marx created mosaics out of plant life. His sketches were vibrant, swirling with shapes that merged painting and landscape design. They highlight how bold lines and color blocks can energize a garden space (Land8).

By observing these figures, contemporary designers can discover new ways to depict light, movement, and the interplay of open space. Some might even fuse historical techniques with modern abstractions to generate striking, innovative compositions.

Cultivate a lifelong practice

In a world where technology evolves overnight, the humble pencil or pen still offers a timeless path to skill development. Designers who train the hand and the eye never stop learning, no matter how advanced their digital prowess becomes. Sasaki Associates regards sketching as a “lifelong practice,” with each new project introducing a fresh puzzle that begs for a crisp line or a quick shading pass (Sasaki).

Keep sketchbooks for each project

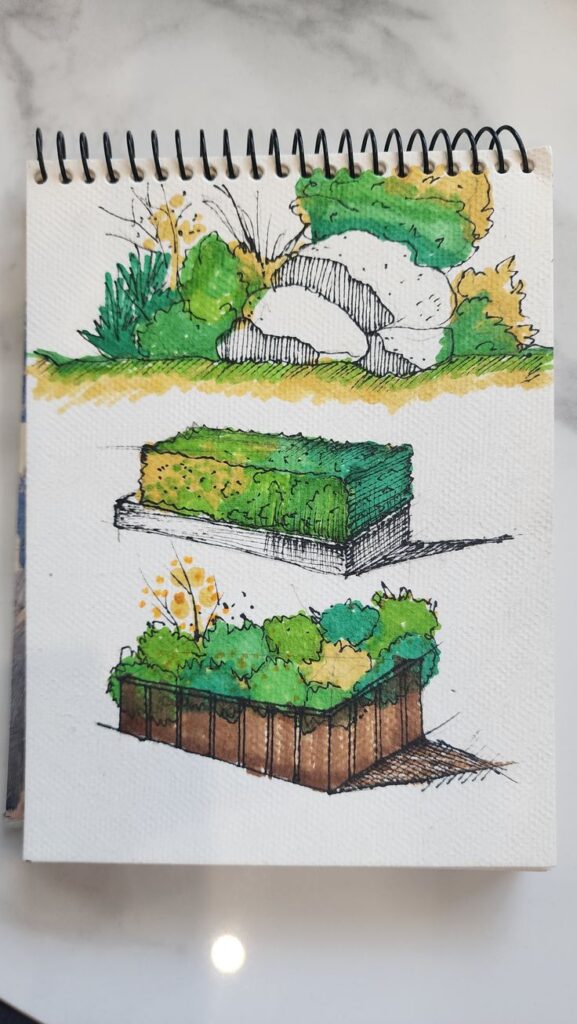

Some designers label sketchbooks for specific ventures—like “Riverside Park Redevelopment” or “Downtown Community Plaza.” Six months or six years later, flipping through those pages reveals how ideas were born, refined, or set aside.Explore new mediums

Charcoal, markers, ink washes—each medium triggers a different perspective. Charcoal might evoke moody renderings, while bright markers play up color-coded zones. These experiments enrich a designer’s visual vocabulary.Engage in field sketches

Visiting the site is essential. Whether it is a campus courtyard or a rugged hillside, turning direct observation into a quick sketch teaches designers new lessons every time. They can note how sun angles shift or how wind patterns might affect vegetation.Encourage peer critique

A sketch only gathers dust if never shared. Mentor-and-peer feedback reveals fresh angles, especially if someone outside the core design team weighs in with a new lens on the project’s aims.

Those who invest in daily or weekly practice build a reflex for seeing natural patterns, shapes, and proportions that lie beneath the surface of any project. That diligence ultimately leads to more thoughtful, harmonious landscapes.

Common questions answered

What are the main benefits of hand sketching over digital rendering?

Hand sketching captures spontaneity and builds a tangible connection to the environment. Designers can iterate faster and allow creativity to flow intuitively. According to Richard E. Scott, clients often respond more enthusiastically to hand-drawn visuals because they convey warmth and authenticity (Land8).

Can beginners adopt the same exercises professionals use?

Absolutely. Exercises like The Timed Sketch, 100 Leaves, and The Daily Diary can be tailored to any skill level. Draftscapes emphasizes that consistency is the most important factor—improvement unfolds gradually with repeated practice (Draftscapes).

Should designers focus on specialized sketching tools?

Not necessarily. Many practitioners enjoy working with simple pencils, pens, or markers. They advise staying comfortable and not obsessing over having the “perfect” kit. Each sketch is part of a personal journey, and the choice of tools should reflect the designer’s natural preferences.

How do sketches integrate with advanced technology?

Many landscape architects begin by sketching initial concepts by hand, then transition to digital models for precision. They see the two approaches as complementary—hand-drawn ideas capture creativity, while digital tools refine scope, scale, and structural feasibility. Sasaki Associates recommends maintaining this balance for best results (Sasaki).

Do sketches help with client engagement?

Yes. Hand sketches often evoke curiosity and collaboration. Clients see that ideas are evolving in real time, which encourages them to share feedback. This dynamic approach feels more like co-creation than a top-down reveal, making clients feel invested in the final outcome.

Landscape architecture sketches do more than shape gardens or parks—they unlock entire worlds of creativity and collaboration. In each stroke, a designer maps out not only trees and pathways but also an experience that can spark awe, reflection, and belonging. From historical masters like André Le Nôtre to modern leaders at Sasaki Associates, sketching continues to bridge the gap between dreams and reality. Those who pick up a pencil and commit to the daily practice of looking, interpreting, and drawing discover how a landscape’s mysteries come to life on each humble sheet of paper. They see how lines transform into winding walkways, how scribbles can grow into a grand public plaza, and how ideas float effortlessly from mind to matter. In these sketches lie possibilities that invigorate design—and invite others to imagine a brighter, greener tomorrow.

- 227shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest227

- Twitter0

- Reddit0