Every character I drew for years had the same body. Different faces, different hair, different clothes—but strip away the costumes and they were all the same person underneath. Athletic but not too muscular. Average height. Narrow waist. The “default” human that exists in tutorials but rarely in actual life.

The problem became obvious when I tried drawing my family from a photo. My grandmother’s soft, rounded silhouette. My uncle’s broad shoulders and barrel torso. My cousin’s tall, angular frame. None of them fit the proportions I’d memorized, and suddenly my drawings looked wrong—not because my technique had failed, but because I only knew how to draw one body type.

Here’s what most figure drawing instruction gets wrong: it teaches a single idealized form as if it’s universal anatomy. The 8-head athletic build works great for superhero comics and fashion illustration, but it represents maybe 10% of actual humans. Real bodies vary dramatically in proportion, weight distribution, and silhouette—and capturing that variation requires different technical approaches, not just different amounts of shading.

- The Real Differences Between Body Types

- Proportion Systems for Different Body Types

- Techniques for Drawing Diverse Bodies

- Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

- Anatomy Considerations by Body Type

- Building Your Reference Library

- Practical Exercises

- FAQ

- Why do my diverse bodies still look like my default body type?

- What reference works best for learning body diversity?

- Do I need to learn different anatomy for different body types?

- How long does it take to get comfortable drawing diverse body types?

- How do I draw larger bodies without it looking offensive?

- Conclusion

This guide covers body types drawing as a practical skill. Understanding how proportions actually vary opens up your entire range as an artist. If you can only draw one kind of body, you can only draw one kind of character.

The Real Differences Between Body Types

Before drawing diverse bodies, you need to understand what actually varies between them. It’s not “draw the same figure but wider” or “add more curves.” The underlying skeletal proportions, muscle visibility, and fat distribution patterns differ systematically.

Skeletal Frame Variations

The skeleton itself varies significantly between individuals. Shoulder width ranges from narrow (shoulders barely wider than head) to broad (shoulders 2.5+ head widths). This single measurement dramatically changes silhouette.

Hip width varies independently of shoulders. Some people have narrow hips regardless of body fat; others have wide pelvic structures that remain wide even at low weights.

Torso-to-leg ratio determines whether someone looks “long-legged” or “long-waisted.” Standard proportions put the midpoint at the crotch, but real people vary significantly.

Ribcage shape can be narrow and deep, wide and flat, or barrel-shaped. This affects how clothing fits and where the waist appears.

When drawing different body types, I start with these skeletal decisions before adding any soft tissue. The skeleton determines the fundamental silhouette—everything else layers on top.

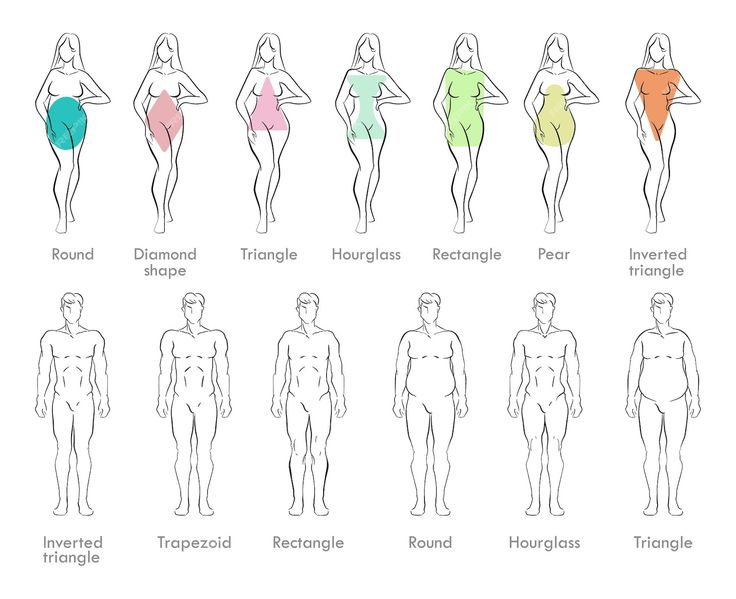

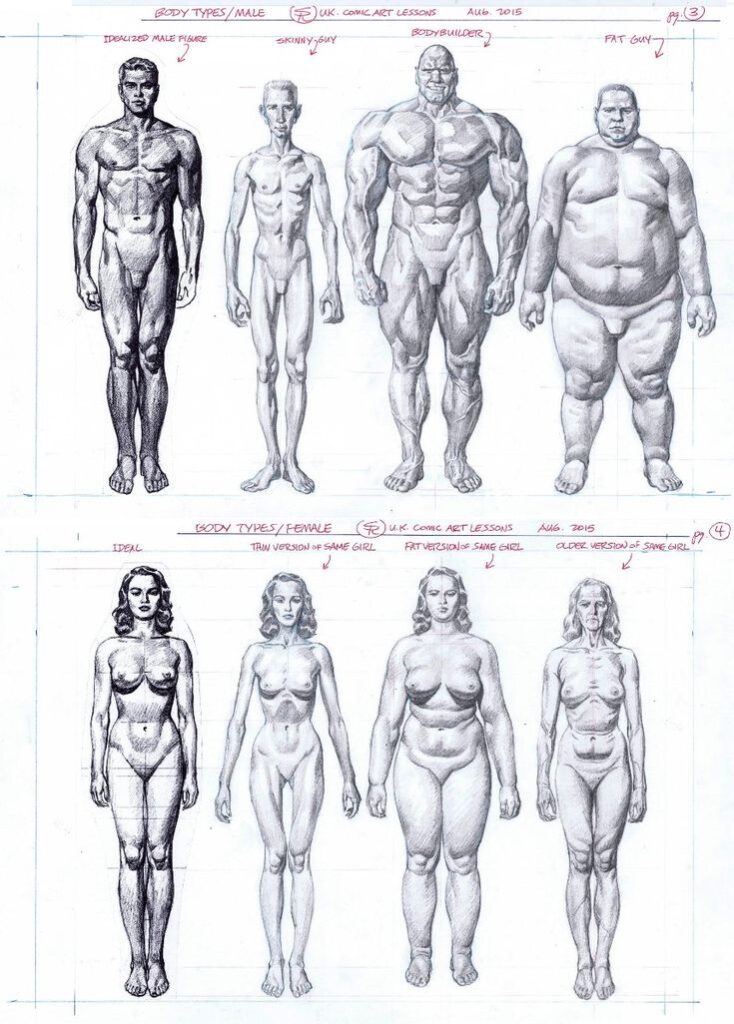

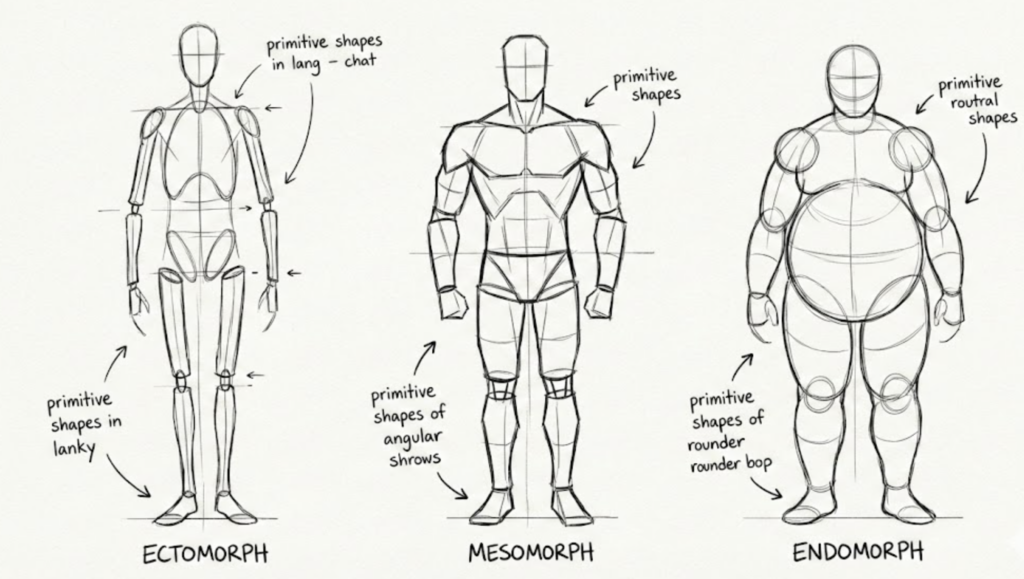

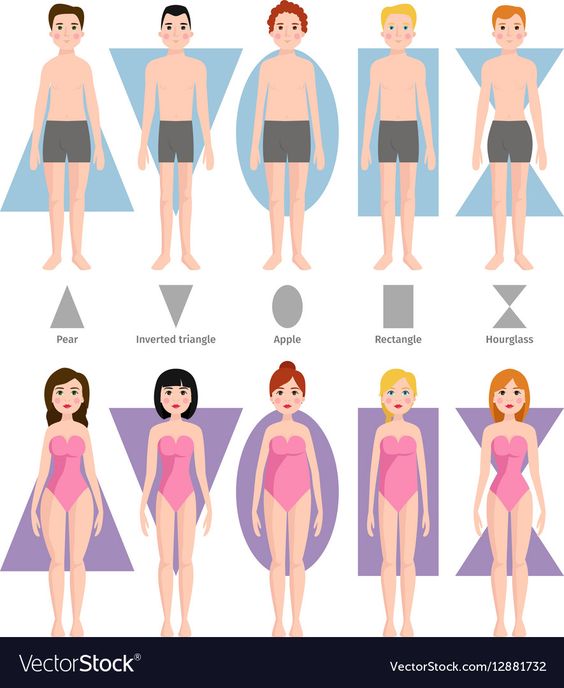

The Somatotype System

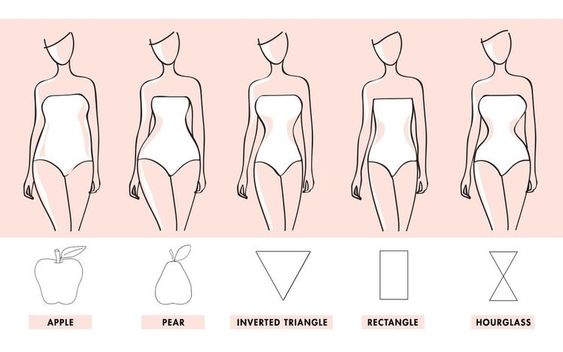

The classic body type categories provide a useful starting framework:

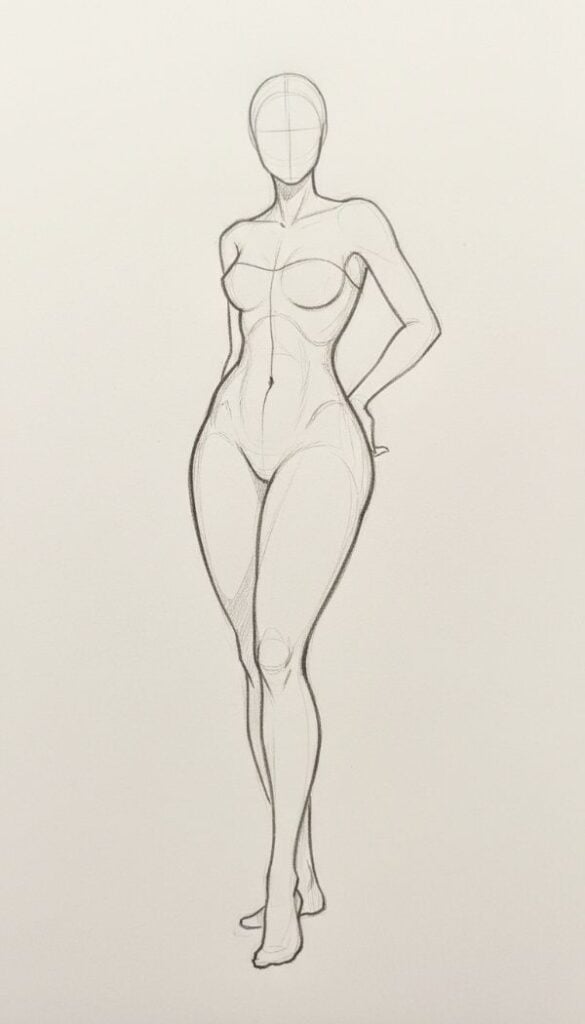

Ectomorph (Linear): Narrow shoulders and hips, long limbs relative to torso, minimal body fat, vertical emphasis in silhouette. Proportions often 8+ heads tall because limbs are long relative to head size. Think marathon runners, fashion models.

Mesomorph (Athletic): Broader shoulders than hips, naturally muscular build, medium bone structure, proportions close to the standard 8-head canon. Visible muscle definition even without extreme training. Think swimmers, gymnasts.

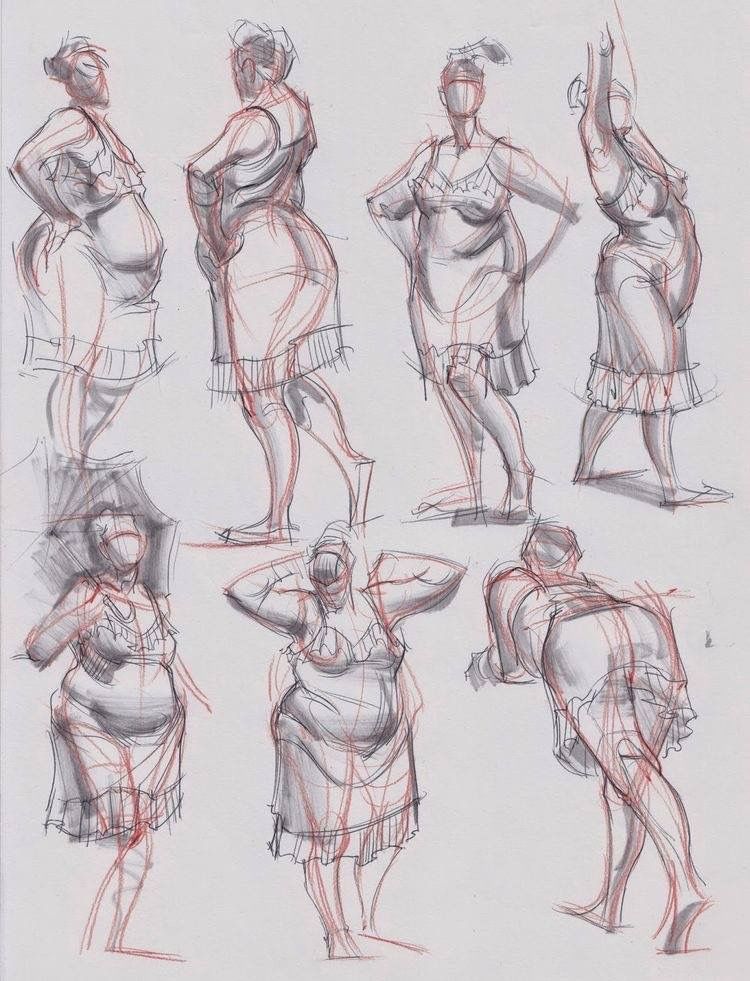

Endomorph (Soft): Wider hips and midsection, rounder overall shape, shorter limbs relative to torso, proportions closer to 7-7.5 heads. Stores fat easily. Think many powerlifters, most of the historical population before industrial food.

Real people are combinations—”ecto-mesomorph” or “endo-mesomorph”—but understanding the pure types helps you see what varies.

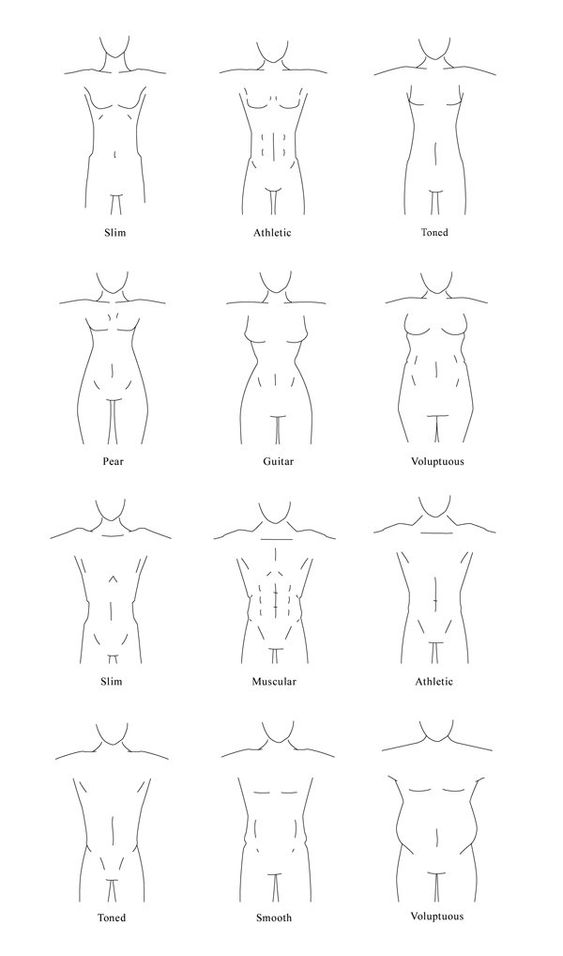

Where Bodies Store Weight

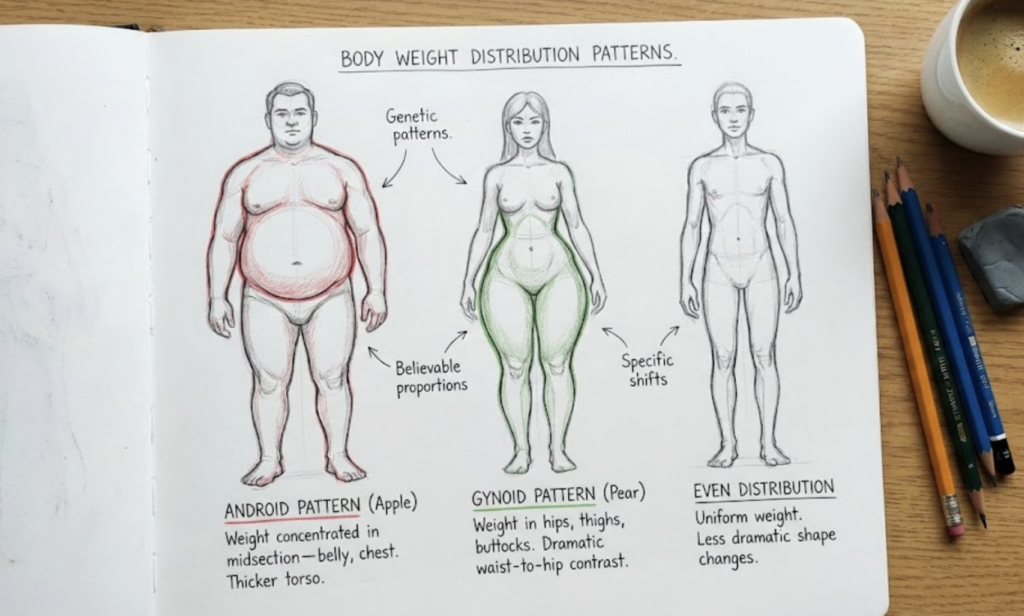

Fat distribution follows genetic patterns that differ by individual and sex:

Android pattern (apple): Weight concentrated in midsection—belly, chest, upper back. Common in males but occurs in females too. Creates thicker torso, relatively thinner limbs.

Gynoid pattern (pear): Weight concentrated in hips, thighs, and buttocks. More common in females. Creates dramatic waist-to-hip contrast, fuller lower body.

Even distribution: Weight distributed relatively uniformly. Less dramatic shape changes with weight fluctuation.

Understanding these patterns helps you draw believable bodies at different weights. A person with android distribution doesn’t just get “bigger”—their proportions shift in specific ways.

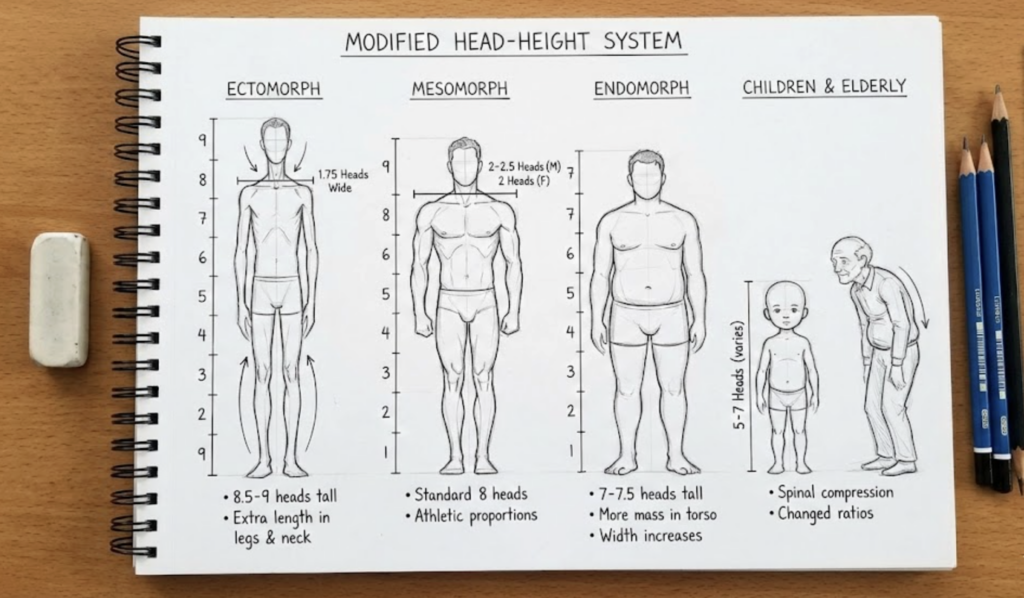

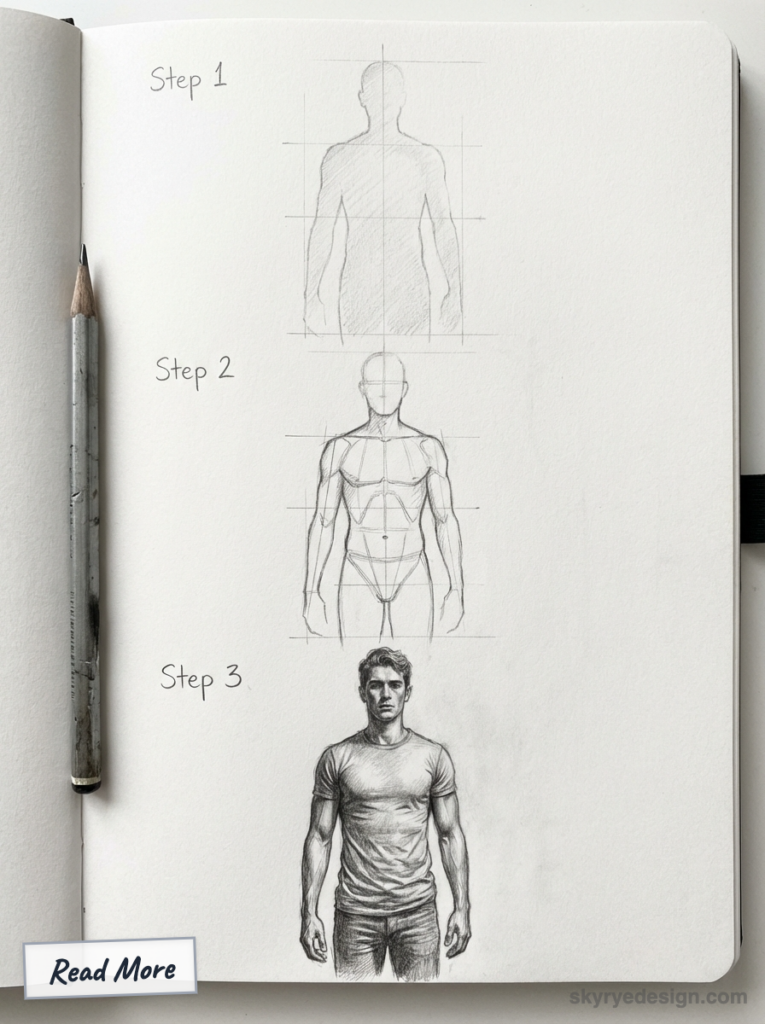

Proportion Systems for Different Body Types

The standard 8-head figure is one proportion system, not the only one. Here’s how to modify proportions for different body types.

Modifying the Head-Height System

For ectomorphs: Consider 8.5-9 heads total height. The extra length typically appears in the legs and neck. Narrower overall width—shoulders might be only 1.75 heads wide.

For mesomorphs: Standard 8 heads works well. Shoulder width around 2-2.5 heads for males, 2 heads for females. Athletic proportions are what this system was designed for.

For endomorphs: Consider 7-7.5 heads total height. Not because endomorphs are necessarily shorter, but because the head-to-body ratio shifts—more mass is in the torso. Width increases proportionally.

For children and elderly: Different proportions again. Children have proportionally larger heads (5-7 heads depending on age). Elderly figures often show compression in the spine, changing the torso-to-leg ratio.

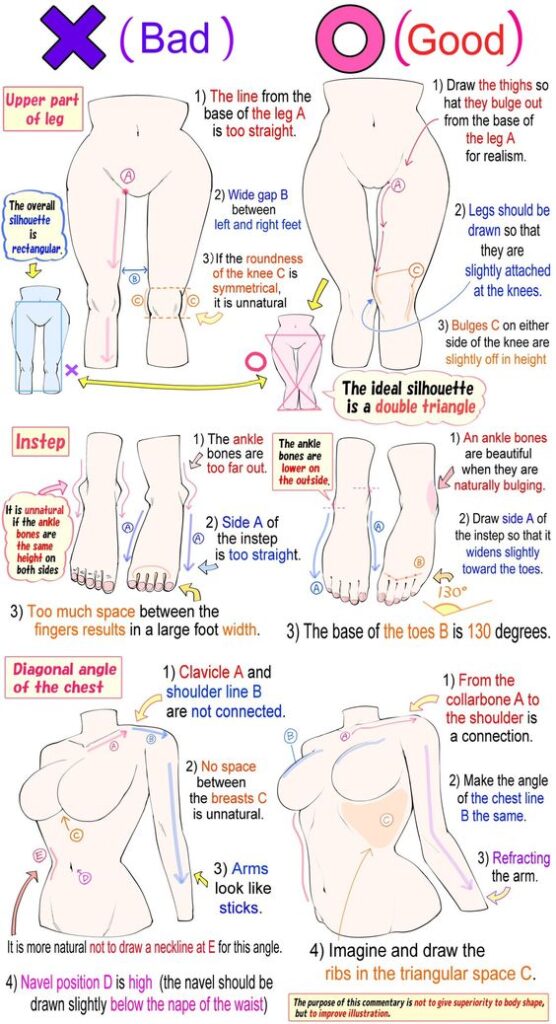

Key Landmark Adjustments

Certain landmarks shift with body type:

Waist position: On lean bodies, the natural waist is clearly visible at the narrowest point of the torso. On bodies with more fat, the “waist” may be less defined or positioned differently.

Elbow-to-waist alignment: Standard proportion places elbows at waist level. This remains roughly true across body types, but “waist level” itself moves.

Fingertip position: Standard proportion places fingertips at mid-thigh. This shifts with arm length—ectomorphs may have longer arms reaching lower; endomorphs may have proportionally shorter arms.

Knee position: Should fall at approximately 2 heads from the ground. Leg length variation changes this landmark’s position relative to total height.

Techniques for Drawing Diverse Bodies

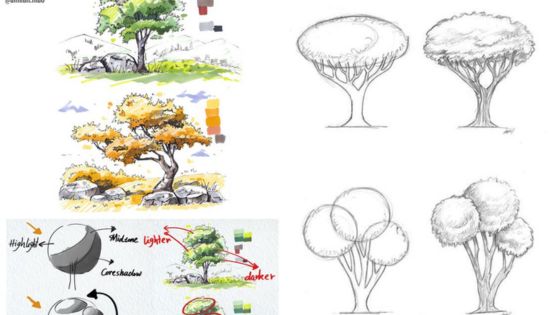

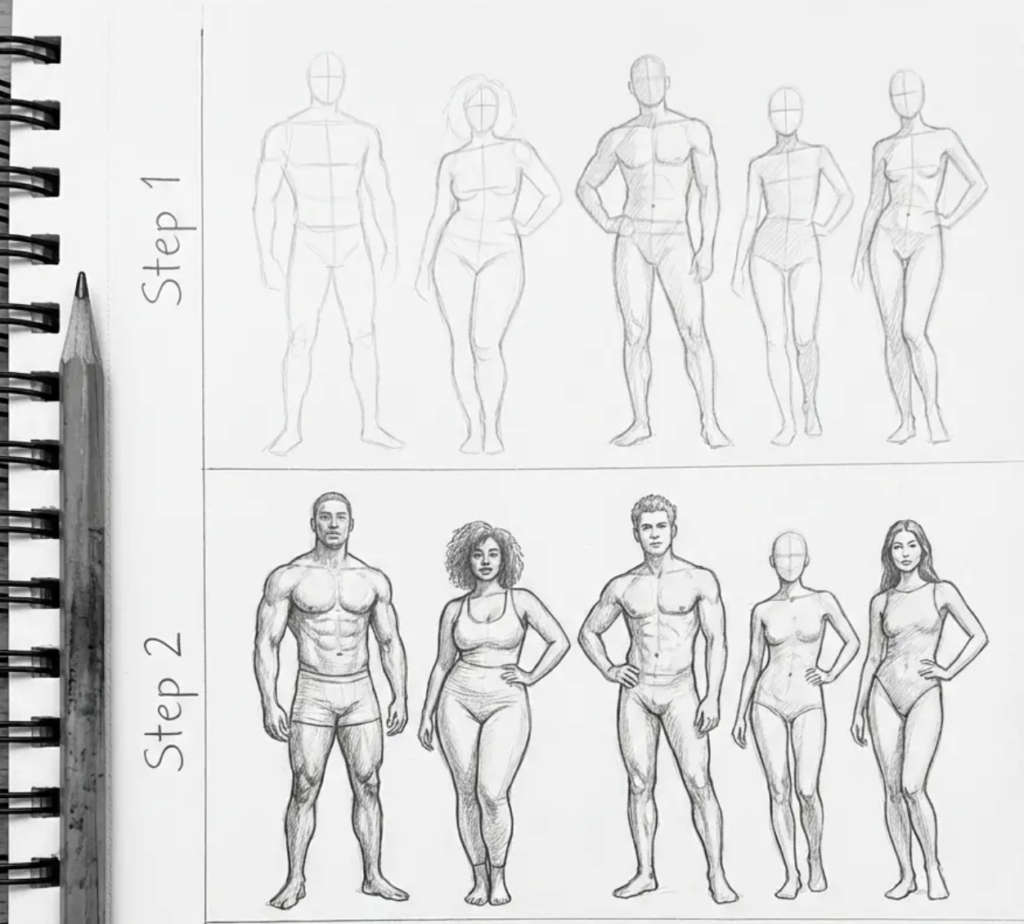

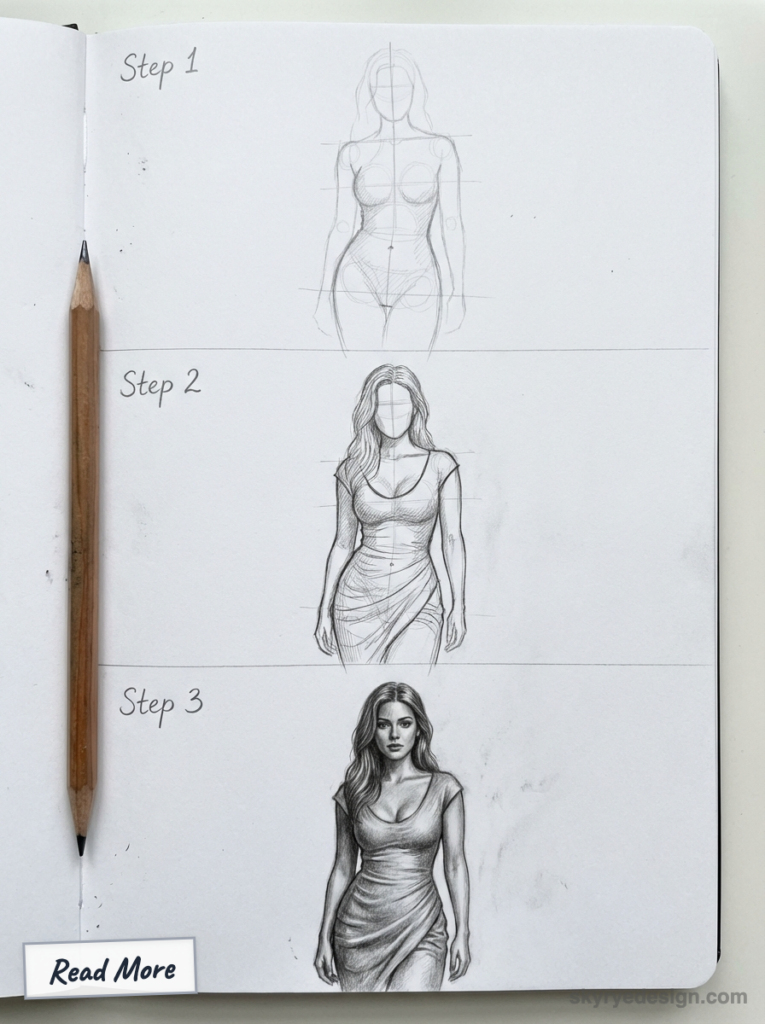

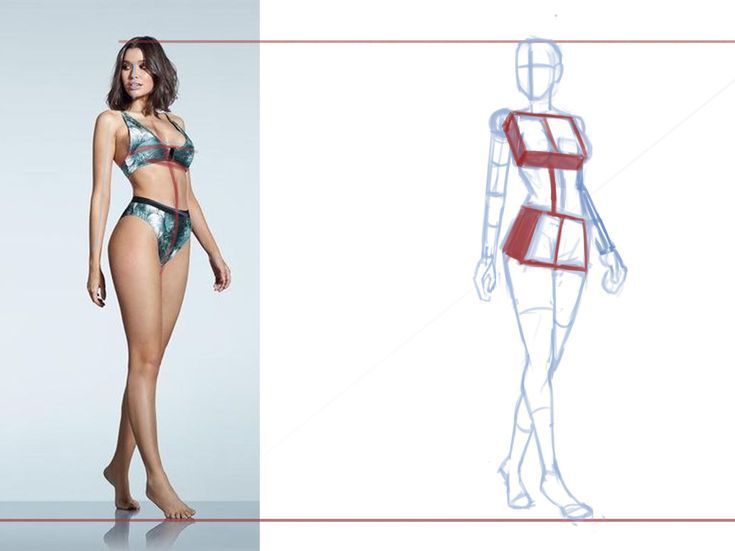

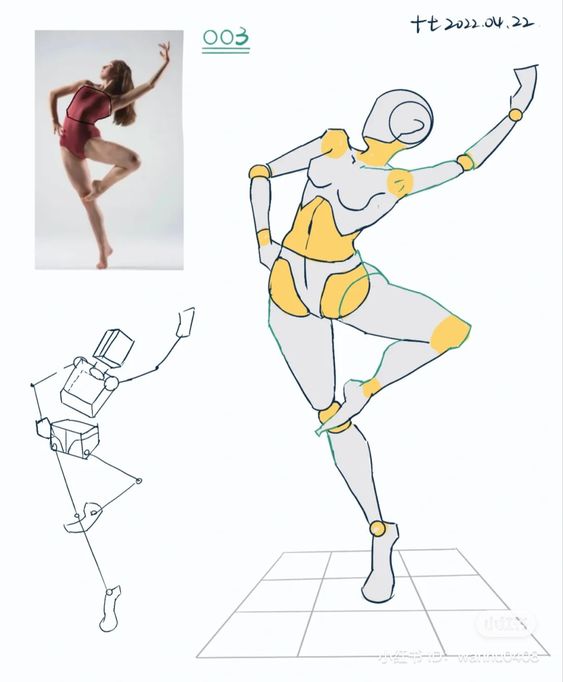

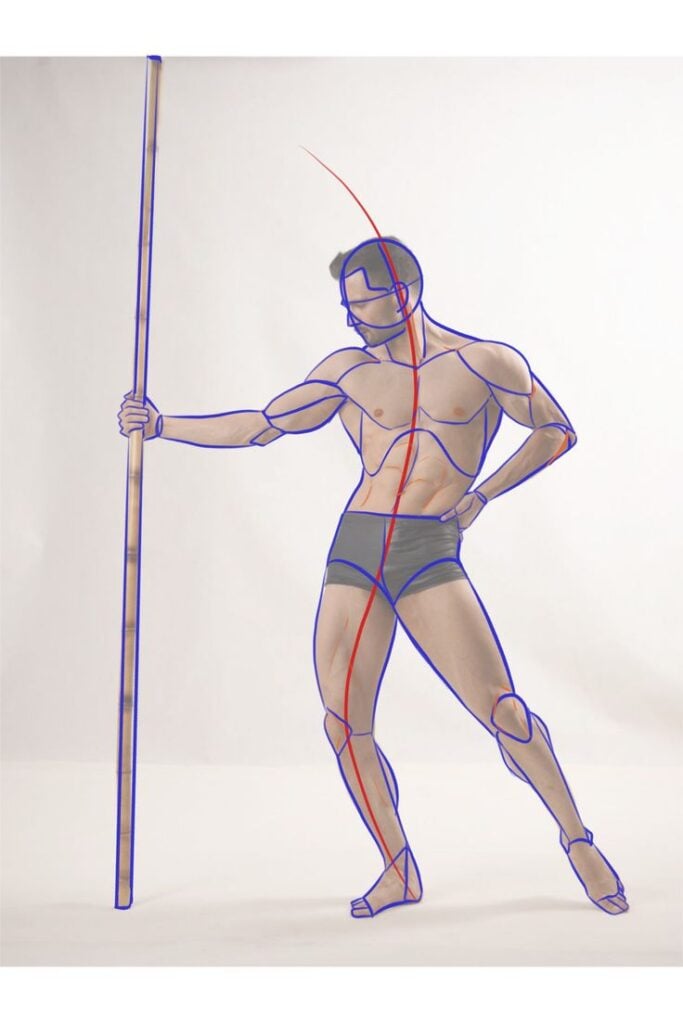

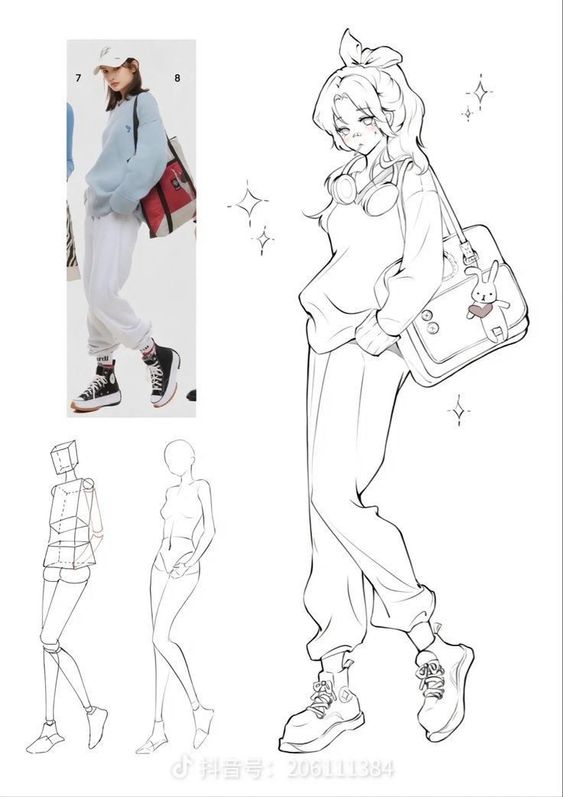

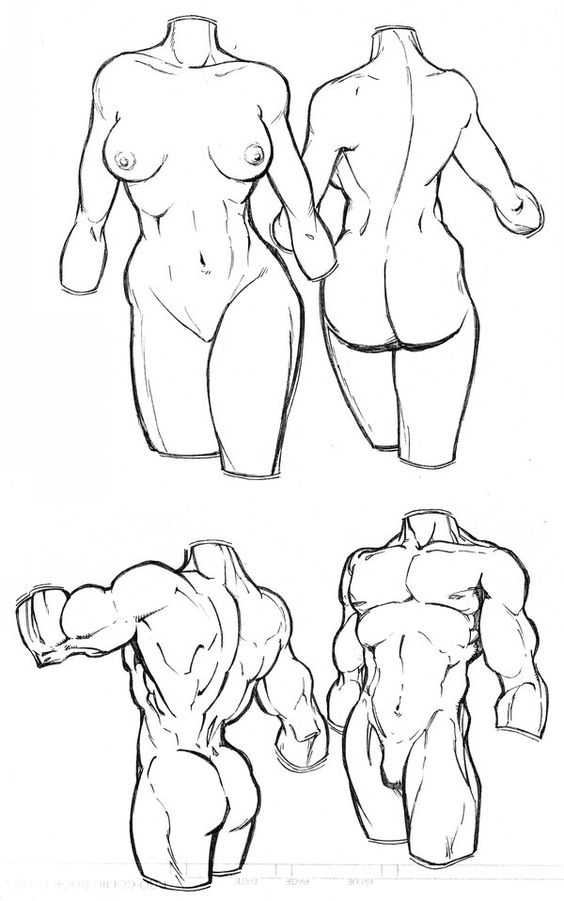

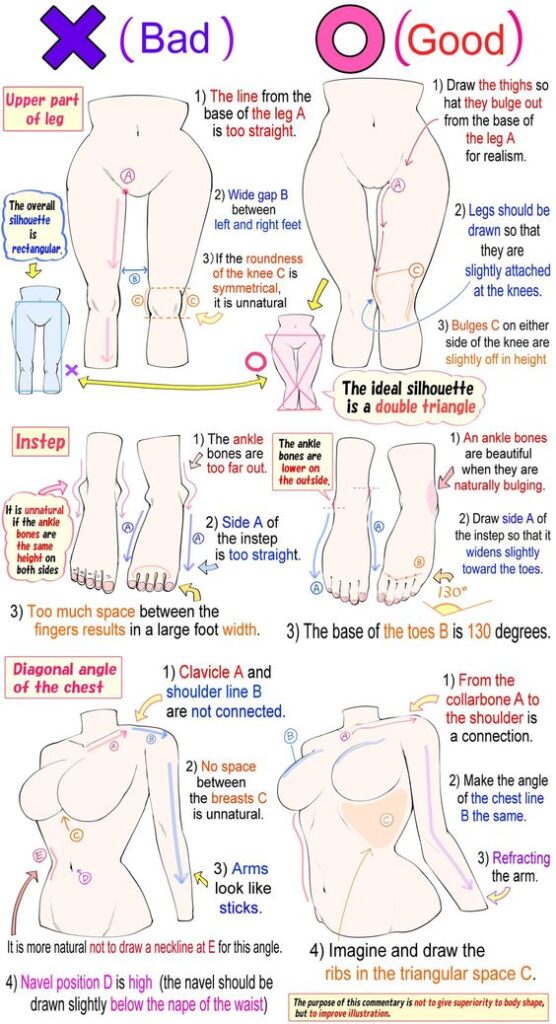

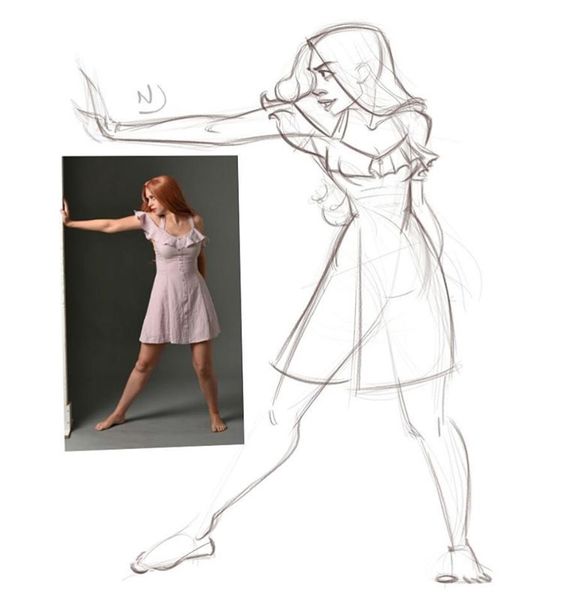

Silhouette-First Approach

The fastest way to establish body type is through silhouette. Before any internal details, block in the outer shape:

Step 1: Draw just the outline—no features, no clothing, no internal lines. Can you identify the body type from silhouette alone?

Step 2: Check key ratios in your silhouette. Shoulder-to-hip relationship. Torso-to-leg proportion. Where the widest and narrowest points fall.

Step 3: Only after the silhouette reads correctly, add internal structure—skeleton landmarks, major muscle groups, then details.

I use this approach for every figure now. It catches proportion problems before I’ve invested time in details that would need to move.

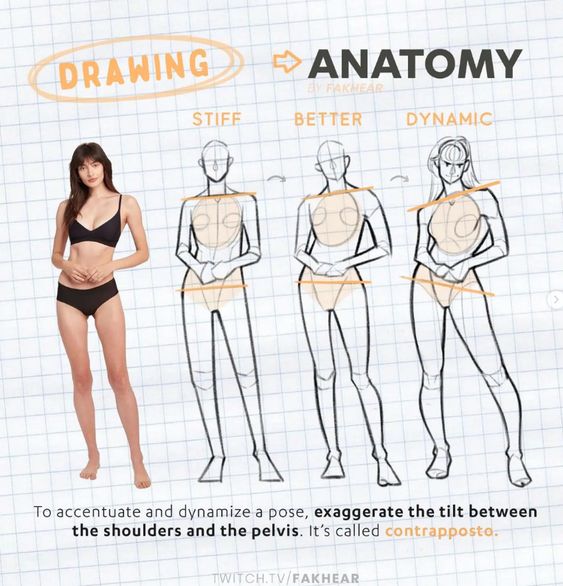

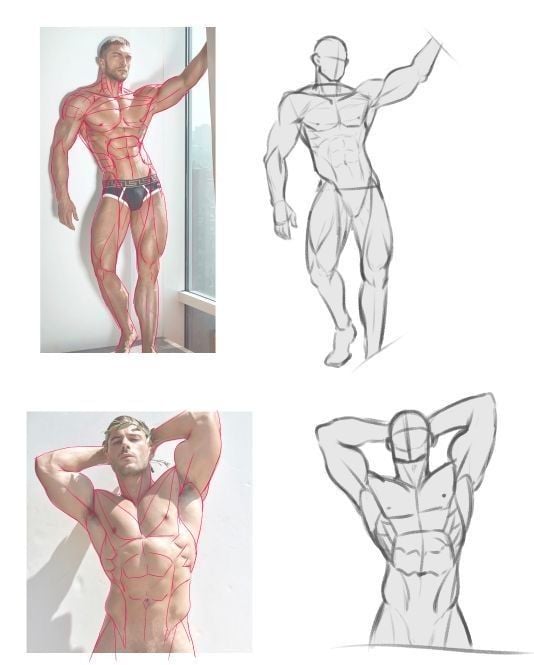

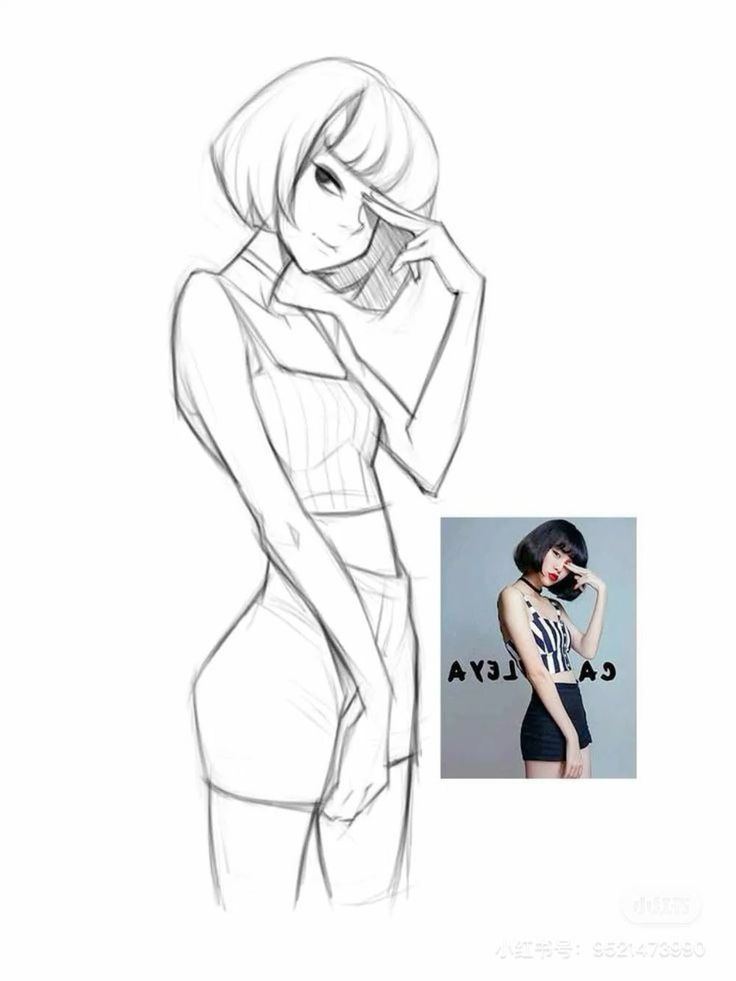

Gesture Drawing for Different Bodies

Gesture drawing typically emphasizes flow and movement—but gesture varies by body type too:

Lean bodies have more angular, longer gesture lines. The flow follows bone structure more directly.

Muscular bodies have gesture lines that curve around volume. The mass affects how movement flows through the figure.

Heavier bodies require gesture that accounts for weight and how it moves. The gesture of a heavy person sitting differs from a lean person sitting—weight settles differently.

Practice gesture drawings specifically targeting body types outside your default. Use timed pose references that feature diverse models.

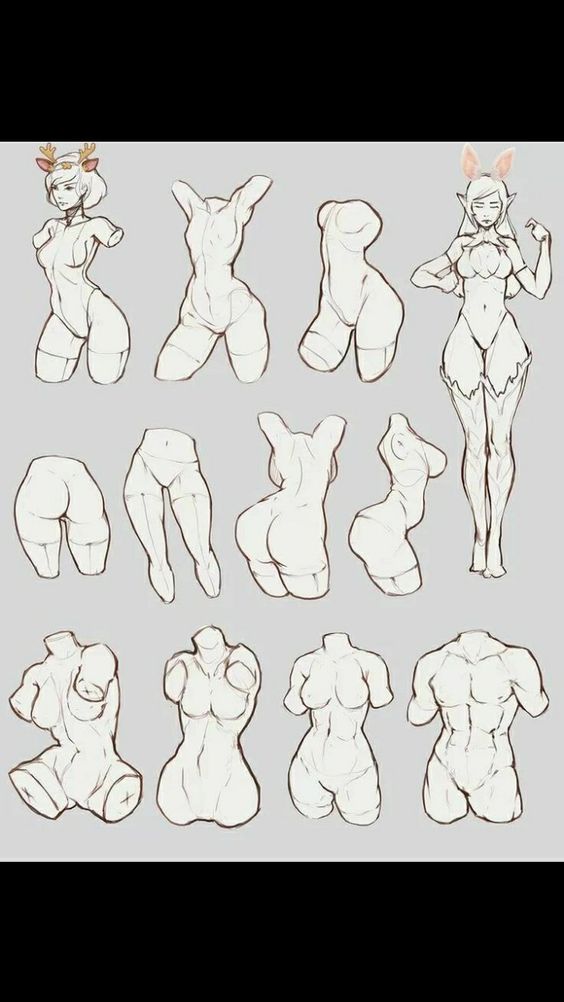

Construction Methods

Build different bodies using different primitive shapes:

Ectomorph construction: Cylinders and elongated ovals. Minimal overlap between body sections. The ribcage and pelvis are more separated.

Mesomorph construction: Tapered cylinders showing muscle bulk. Clear V-shape from shoulders to waist (especially males).

Endomorph construction: Spheres and rounded forms. More overlap between sections—the torso flows into hips without dramatic waist.

These construction approaches give you different results from the start, rather than trying to modify a single construction method.

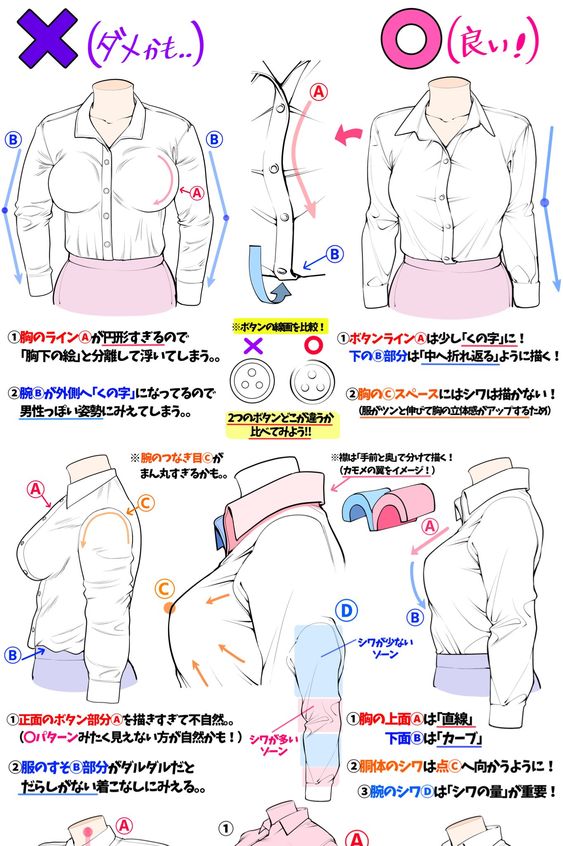

Common Mistakes and How to Fix Them

The “Same Face, Different Size” Problem

Many artists vary body size but not body type. A larger figure is just their default figure scaled up uniformly. This doesn’t match reality—weight affects different areas differently.

Solution: Change proportions, not just scale. A heavier figure has different shoulder-to-hip ratios, different limb-to-torso ratios, different landmark positions. Study reference photos of people at various weights to see how proportions actually shift.

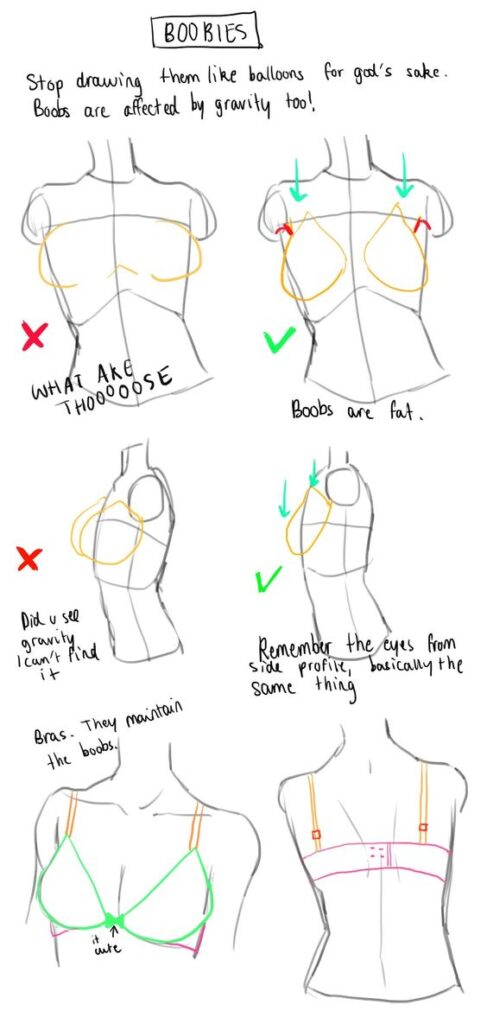

Making Larger Bodies Look Solid, Not Inflated

Beginners often draw larger bodies as if they’re filled with air—round but not heavy. The figures look like balloons rather than people.

Solution: Show weight and gravity. Larger bodies have mass that responds to gravity—tissue settles, weight compresses against surfaces. When drawing a larger person sitting, show how their weight presses into the seat. Standing, show how weight distributes through their stance.

Also remember: larger bodies often have underlying structure. A large person may have broad shoulders and visible muscle—they’re not just “soft” everywhere.

Drawing Muscular Bodies Without Anatomy Overload

Highly muscular bodies tempt artists to draw every visible muscle, creating figures that look like anatomy charts rather than people.

Solution: Simplify muscle groups into larger shapes. Even bodybuilders have skin that smooths over the underlying muscles. Show major mass divisions (deltoid, pectoral, quadriceps) without subdividing every muscle head. Save extreme definition for specific contexts like bodybuilding illustration.

Avoiding Caricature and Stereotype

When drawing body types outside your default, there’s risk of exaggeration that becomes caricature—or falling into stereotyped representations.

Solution: Use reference. Always. Not to copy exactly, but to check your instincts against reality. Your mental image of a body type may be more extreme than actual examples. Reference keeps your drawings grounded in real human variation.

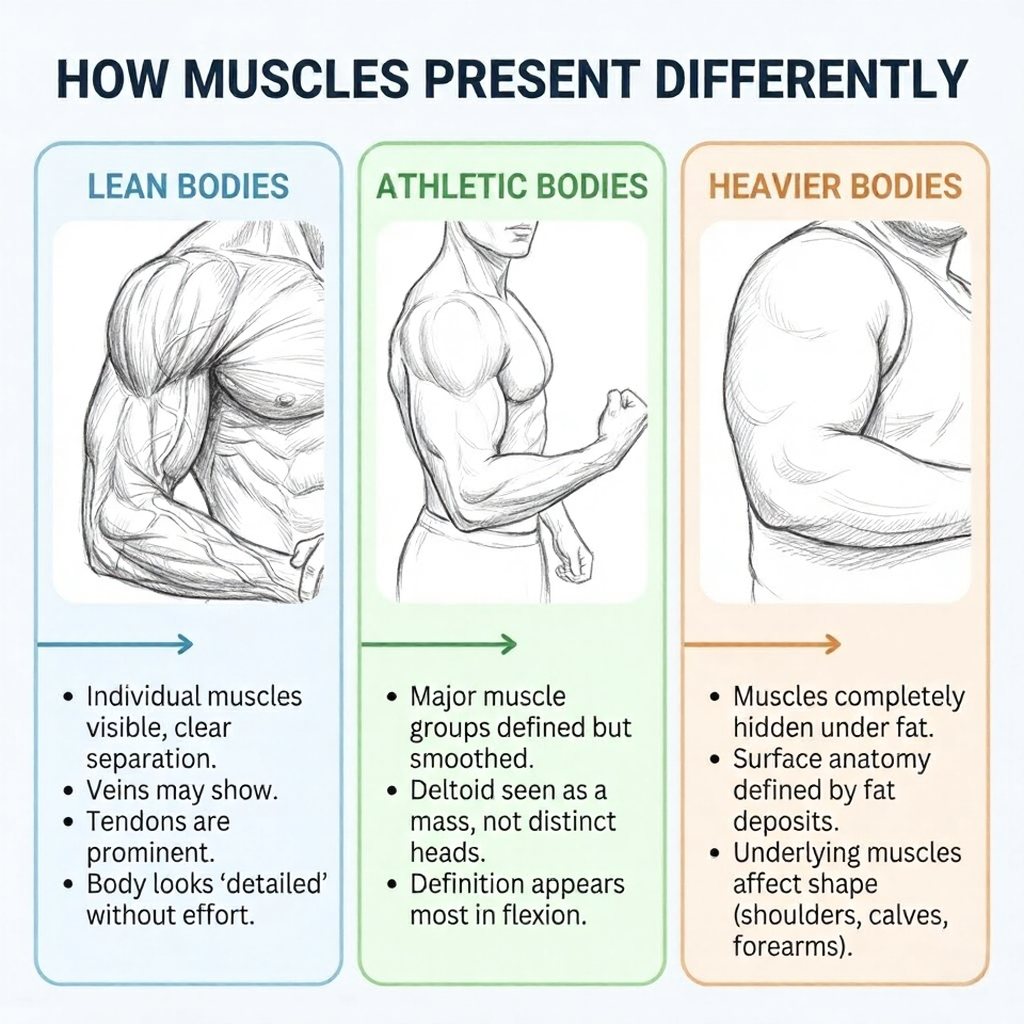

Anatomy Considerations by Body Type

How Muscles Present Differently

Muscle anatomy is the same across body types—the same muscles in the same places. But visibility changes dramatically:

On lean bodies: Individual muscles are visible, sometimes with clear separation between muscle bellies. Veins may show. Tendons are prominent. The body looks “detailed” even without effort.

On athletic bodies: Major muscle groups are defined but smoothed. You see the deltoid as a mass, not three distinct heads. Definition appears most in flexion.

On heavier bodies: Muscles may be completely hidden under subcutaneous fat. Surface anatomy is defined by fat deposits, not muscle topography. However, the underlying muscles still affect shape—especially in the shoulders, calves, and forearms where fat is thinner.

Skeletal Landmarks That Show (or Don’t)

On lean bodies: Collarbones, shoulder blades, spine, hip bones, ribs, knees, ankles—all prominent. These landmarks guide your drawing.

On heavier bodies: Most landmarks are obscured. The landmarks you can see—wrist bones, knuckles, sometimes collarbones—become important anchors.

Practice this: Draw the same pose on different body types. Notice which landmarks remain visible and which disappear. The visible landmarks are your drawing anchors for that body type.

Building Your Reference Library

Where to Find Diverse Reference

Life drawing sessions: Seek out sessions featuring models of various body types. Many communities have body-positive figure drawing events specifically for this.

Stock photo sites: Look for unretouched images. Sites like Human Poses, SenshiStock, and stock libraries offer reference across body types. Organize by body type for quick access.

Medical and fitness resources: Supplement standard anatomy references with resources specifically showing body variation—medical photography, fitness transformation images, anthropological archives.

Real-world observation: Sketch in public spaces. Coffee shops, parks, beaches, transit. You’ll encounter body variety that posed reference often lacks.

Artists to Study

Some artists handle body diversity particularly well:

Rubens: Baroque master of full-figured bodies. Study how he rendered weight, softness, and volume.

Lucian Freud: Unflinching figure paintings showing bodies of all types. Excellent for understanding how fat and muscle actually look in paint.

Jenny Saville: Contemporary painter of monumental figures. Studies mass, flesh, and skin at large scale.

Character designers at Pixar/Disney: Recent films show dramatically improved body diversity. Study how they simplify complex body types into readable silhouettes.

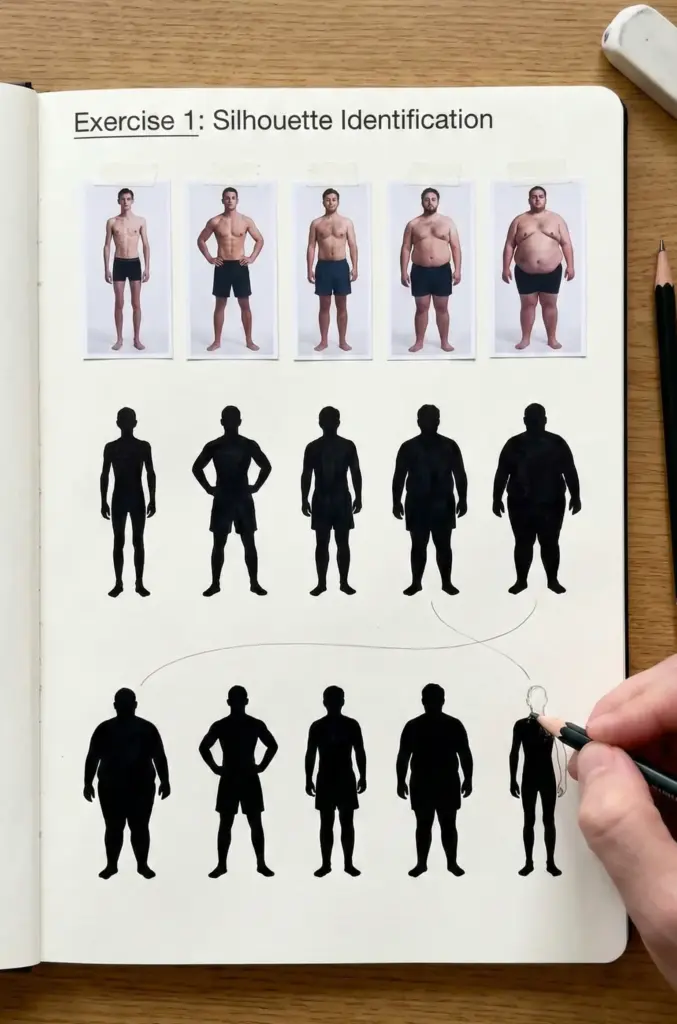

Practical Exercises

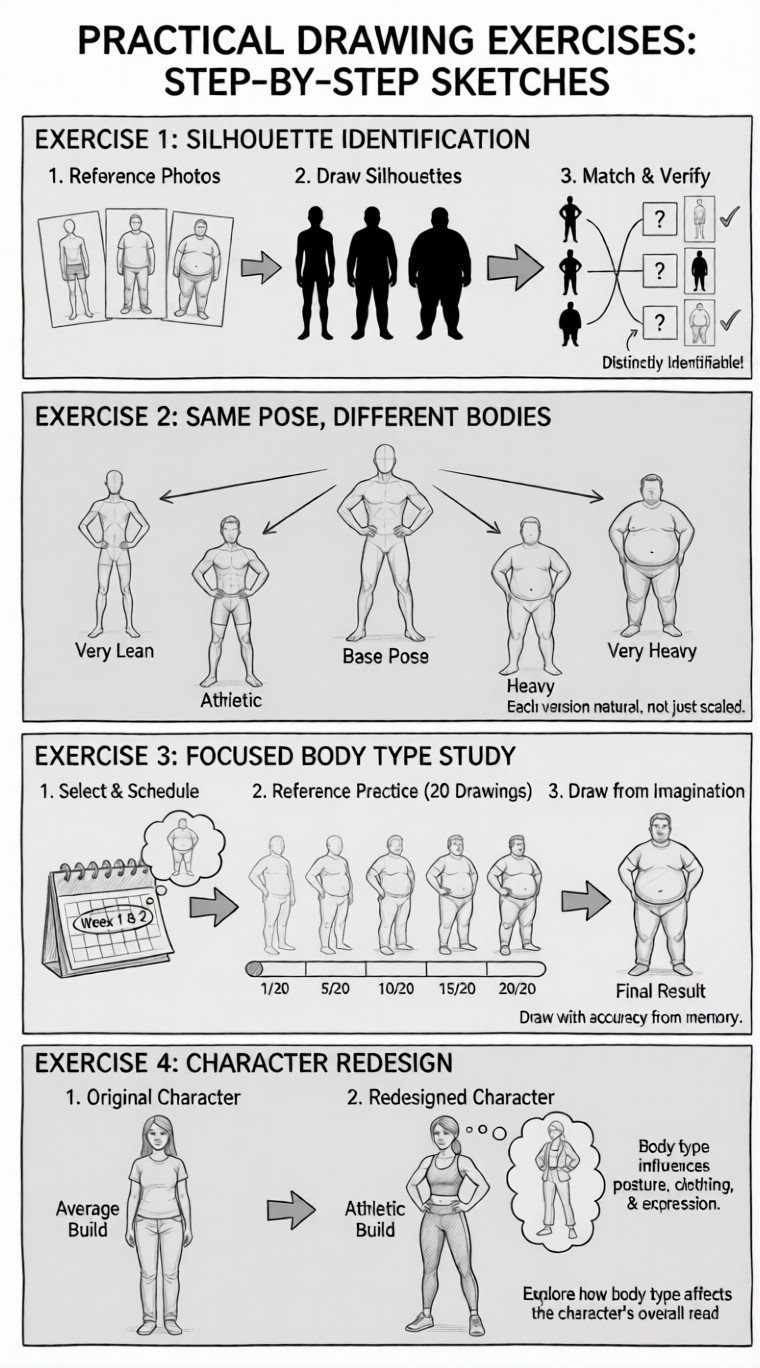

Exercise 1: Silhouette Identification

Find reference photos of 5 distinctly different body types. Draw just the silhouettes—no internal detail. Shuffle the silhouettes and try matching them to originals. If they’re not distinctly identifiable, your differentiation isn’t strong enough.

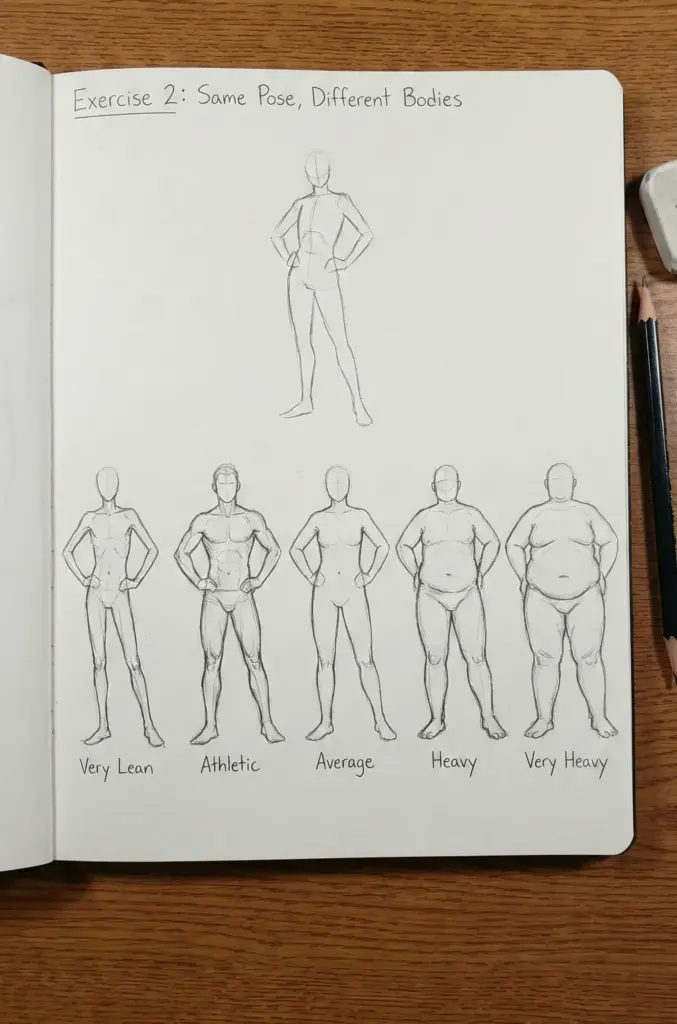

Exercise 2: Same Pose, Different Bodies

Choose a single pose and draw it as 5 different body types: very lean, athletic, average, heavy, very heavy. Each version should look natural and comfortable—not the same drawing scaled differently.

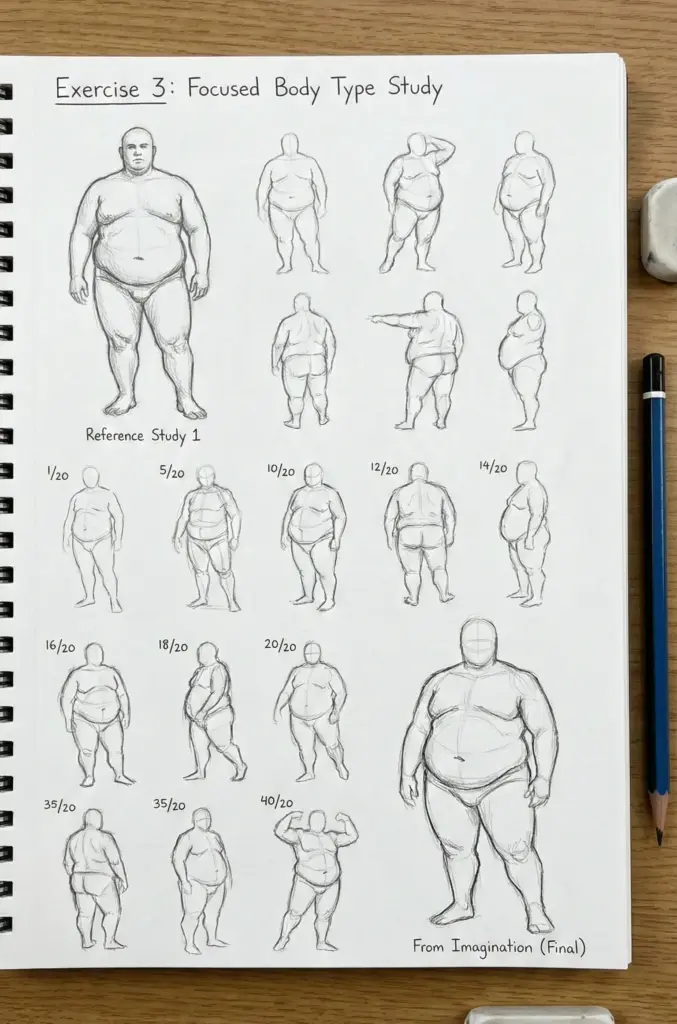

Exercise 3: Focused Body Type Study

Select one body type outside your comfort zone. Do 20 drawings of this type over two weeks, always from reference. By the end, you should be able to draw this body type from imagination with reasonable accuracy.

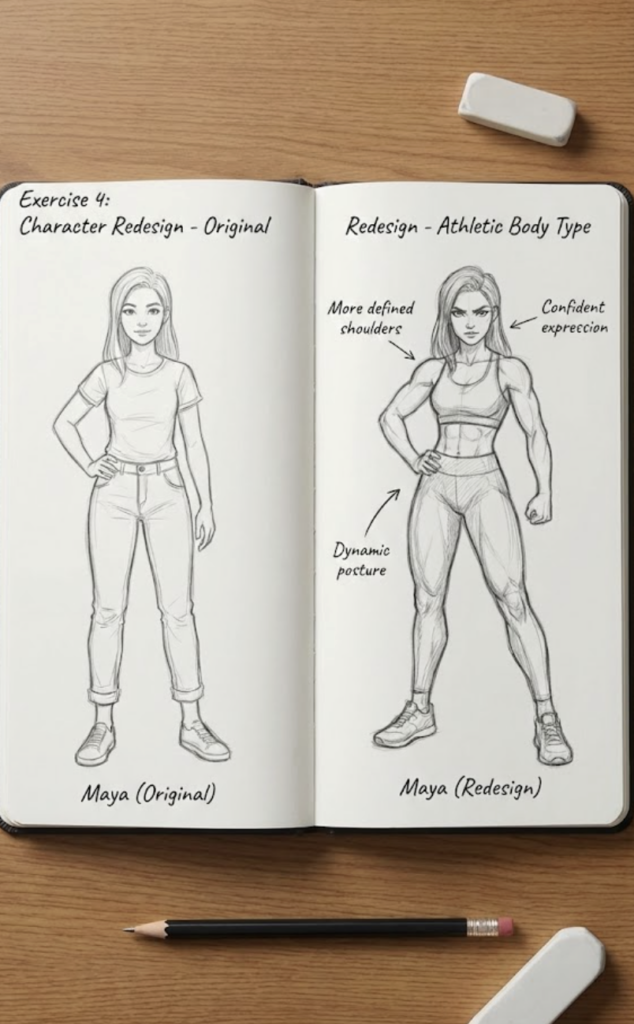

Exercise 4: Character Redesign

Take characters you’ve already designed and redesign them with different body types. How does the character read differently? What changes beyond the body—clothing, posture, personality expression?

FAQ

Why do my diverse bodies still look like my default body type?

You’re maintaining your usual proportions and just changing surface details. Body type is structural—it requires changing the underlying skeleton and proportion relationships, not just adding curves or width. Use the silhouette test: if you can’t identify the body type from outline alone, the difference isn’t structural enough.

What reference works best for learning body diversity?

Life drawing with diverse models is ideal. Failing that, use stock photo sites with unretouched images, medical/anatomical references, and candid photography. Avoid heavily edited images, most fashion photography, and social media photos that may be filtered or posed to alter proportions.

Do I need to learn different anatomy for different body types?

The underlying anatomy is identical—everyone has the same muscles and bones. What changes is visibility (which landmarks show), distribution (where fat accumulates), and proportion (how skeleton dimensions relate). Understanding baseline anatomy helps you understand what’s varying.

How long does it take to get comfortable drawing diverse body types?

With focused practice, most artists see significant improvement in 4-6 weeks. This means actively seeking out challenging body types, not just drawing your default with occasional variation. Dedicated practice of one “uncomfortable” body type for 20 drawings does more than 100 drawings of types you already know.

How do I draw larger bodies without it looking offensive?

Draw them as people, not as types. Use reference to understand how the body actually works rather than relying on stereotyped mental images. Show larger bodies doing the same range of activities as other bodies. Avoid caricature exaggeration. If you’re thinking about this question, you’re probably approaching it thoughtfully enough to do fine.

Conclusion

Body types drawing comes down to one core shift: seeing proportion as variable, not fixed. The 8-head athletic figure isn’t wrong—it’s just one option among many. Every body type has its own proportion logic, its own distribution patterns, its own gesture qualities.

The artists who draw diverse bodies convincingly aren’t working from a representation checklist. They’ve developed genuine technical facility with different proportion systems. They can draw any body type because they understand how bodies actually vary.

This week: Collect reference images for 5 distinctly different body types. Create silhouette studies of each—just outlines, no detail. Can someone else identify which body type is which from silhouettes alone?

Next two weeks: Pick the body type furthest from your default. Do 10 drawings from reference. Focus on proportion relationships, not surface details.

Ongoing: When drawing characters, consciously choose body types rather than defaulting. Ask: what body type suits this character? Then execute that choice deliberately.

I spent years drawing the same body on every character because I didn’t realize I was doing it. The “default” was invisible—it was just “how to draw people.” Breaking that default required conscious effort, but the result was worth it: characters who actually look different from each other, not just in costume and face, but in fundamental physical presence.

Start with the body types you’ve been avoiding. That’s where the growth is.

- 1.8Kshares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest1.8K

- Twitter0

- Reddit0