Key highlights

- Personal taste often overrides brand needs in logo brief

- Too many visual references can confuse rather than clarify

- Local context matters when briefing Australian design agencies

- Clear, specific feedback leads to stronger final designs

You likely have an idea of what you like. Perhaps it is a particular font, a colour scheme you always seem to gravitate towards or a style that feels like you. That’s completely normal. The problem is here though, you might like something that may not be what your brand actually requires.

Many logo briefs are inclined to personal preferences. They will name colours you have always liked, shapes that you like or brands that you like. However, unless the preferences are in line with your audience and industry, they can simply get the design off track. It is the distinction between what appears to be good to you and what conveys the message of your brand.

The focus should be on brand personality. That is to say, what impression would you like to create, confident, approachable, premium, bold? The first thing that people see is your logo. When it is more of your personal style than your business image, then you run the risk of confusing or driving away the people you are after.

Designers are not attempting to impose on you. However, they must know whether you are demanding something that will suit your market, or simply something that will suit your own taste. There is a distinct brief between the two. It describes the type of perception that the logo should produce, and why that is important to your particular business. That scenario assists the designer to make decisions that are not based on guesses but are based on strategy.

In the process of explaining what you want, it seems like the easiest thing to do, to demonstrate what you want. Visual references are frequently requested by designers, and Pinterest boards or screenshots can be used to get the ball rolling. But there’s a tipping point. When the list becomes too long–or too mixed–it may begin to make more confusion than sense.

The Problem with Too Many References

When you are attempting to describe what you desire, it seems the simplest to demonstrate examples in order to make your point. It is common that designers request visual references, and Pinterest boards or screenshots can be used to get things started. But there’s a tipping point. When the list becomes too long–or too mixed–then it may begin to confuse rather than to clarify.

The issue isn’t just volume. It’s the lack of focus. When you send five logos of totally different industries, different styles, moods and design principles, your designer is left to seek a through-line that might not be there. It turns into a game of guessing: what do you like, and why? Out of that context, the references may confuse the waters rather than inform the design.

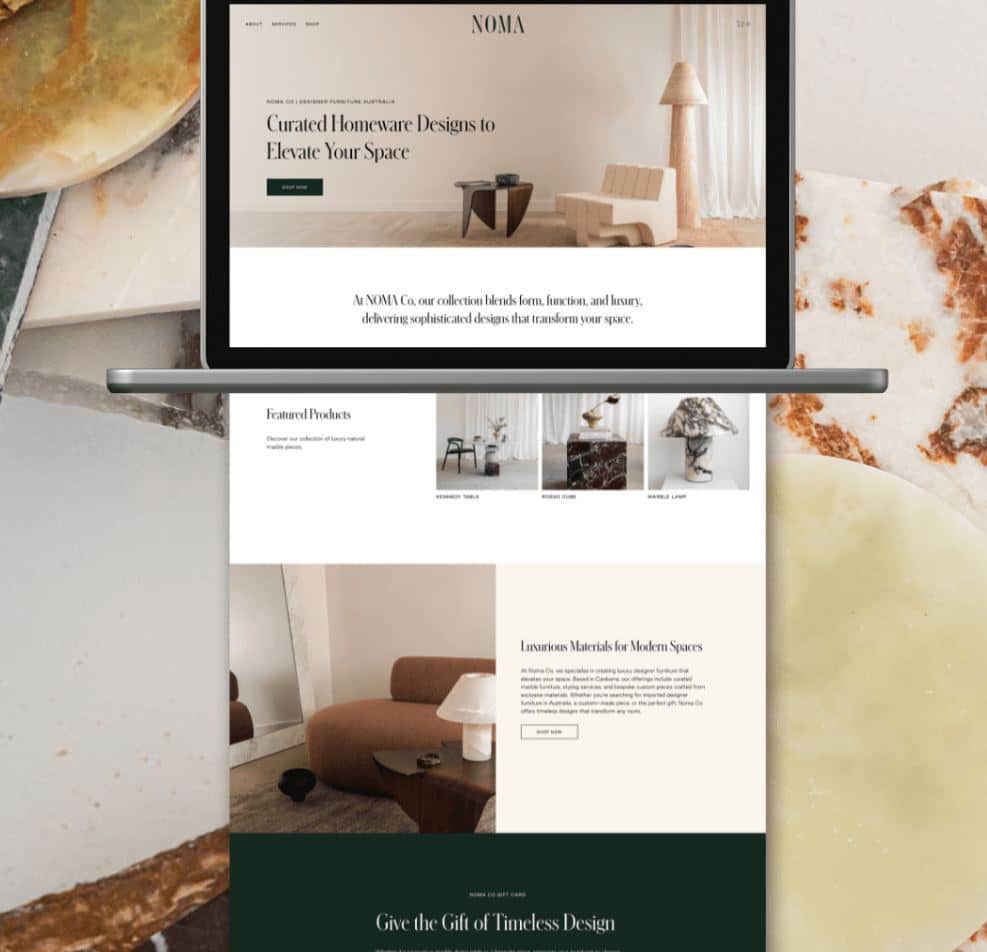

When working with a Brisbane graphic design agency, local context matters too. What appears sleek and minimal on a tech start up in New York may fail miserably on a family-owned business in Queensland. A reference borrowed from a global brand does not always scale down to a cafe, trade service or small eCommerce label. The creative direction is much more helpful when you select the references that represent your business size, market, and industry.

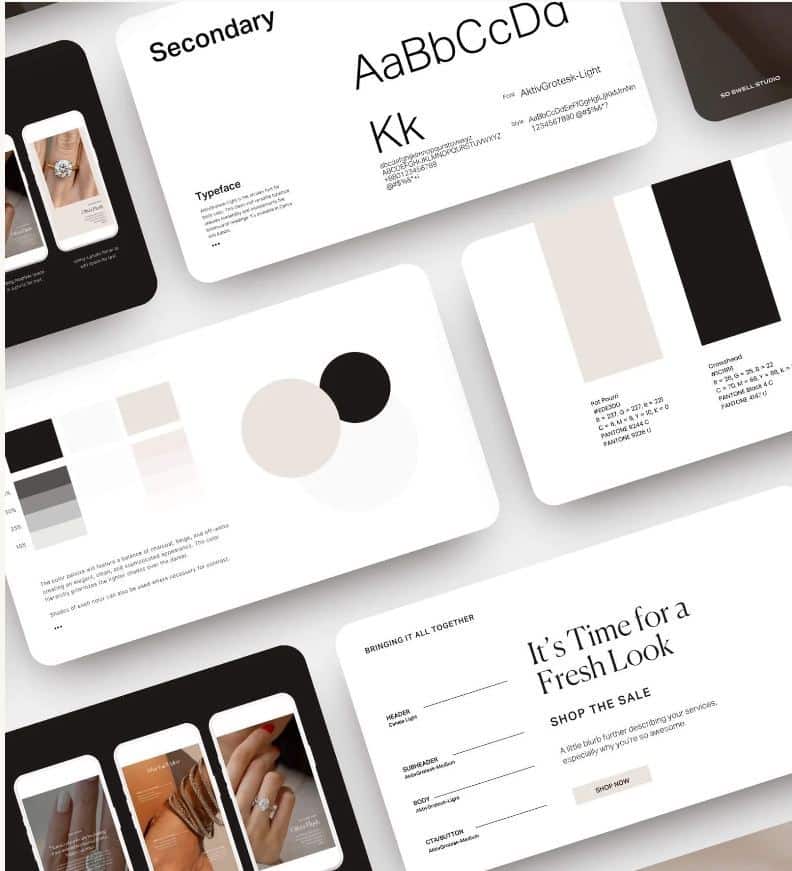

It also serves to prevent the use of logos because they look good. It is a legitimate instinct, but not sufficient. The more powerful one is to say what you like in the logo. Perhaps it feels harmonized or the colour selection is self-assured or the spacing provides the breathing space. Such feedback creates an appropriate design dialogue. It allows the designer to think and not just copy what is already available.

Feedback That Leads to Better Design

Although you have a great brief and a direction, your initial logo idea may not be the best. That’s not a sign of failure. It is a natural aspect of the design process. The next thing will depend on your response.

It is not difficult to say that you do not like something. However, it does not assist the designer to know what is wrong and how to correct it. Specific feedback is the most helpful. When something seems wrong, tell me what you thought you would see or what aspect does not sit well. Perhaps the type is too heavy or the icon too sharp to the tone you desire. Such details provide the designer with something to play with.

Good feedback is also sincere but not prescriptive. It is concerned with the way the design fits your objectives, but not with directions. Direct edits may not be as useful as asking questions. An example is inquiring why a particular shape was employed or how the idea would work on a package, which can result in fruitful discussions. The design is often thought through and the reasoning is not immediately apparent.

It is in this give and take that actual advancement occurs. You are not attempting to dictate every action. You are providing the designer with the input that they require to polish the work and the creative control is retained on your side. It is that balance that results in a more powerful final product and a logo that works to do what it is supposed to do.

A strong logo doesn’t just reflect what you personally like—it signals something clear and intentional to the people you’re trying to reach. That clarity begins with a focused brief and evolves through strategic, thoughtful feedback. Your designer isn’t looking for instructions—they’re looking for understanding. The better you can articulate your brand’s purpose, personality and priorities, the easier it becomes to create something that does more than look good. It starts working.

- 3shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest0

- Twitter3

- Reddit0