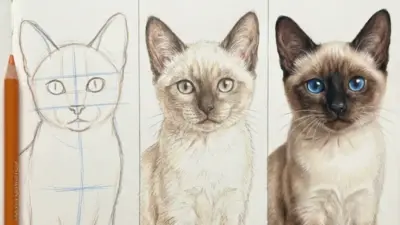

Ever stopped to think about how artists make objects seem like they’re jumping right off the page ? Giving them some serious depth and that illusion of being right in front of you all comes down to one thing: shading. Shading is the secret to turning a flat line drawing into something that looks like its got some real substance to it – a three dimensional form. If you’re looking to get a handle on this essential artistic skill then one good place to start is by learning how to draw a cube with some shading. To be honest, it’s the ultimate first step – a crash course in developing your artistic eye and hand.

Don’t let the cube’s simplicity fool you though. Figuring out how to shade one properly is where you build the foundation that’ll serve you for anything from still life to portraits – even those complex figure drawings. Its all about getting a grip on how light, shadow and they interact – that’s what brings form to life.

Think of it as your first step towards becoming a shading master, someone who can conjure depth and realism out of nothing more than a pencil and a bit of paper. So are you ready to take the plunge on this journey of discovery and get some real insight into shading a cube ? Let’s strip back the mystery of it all together

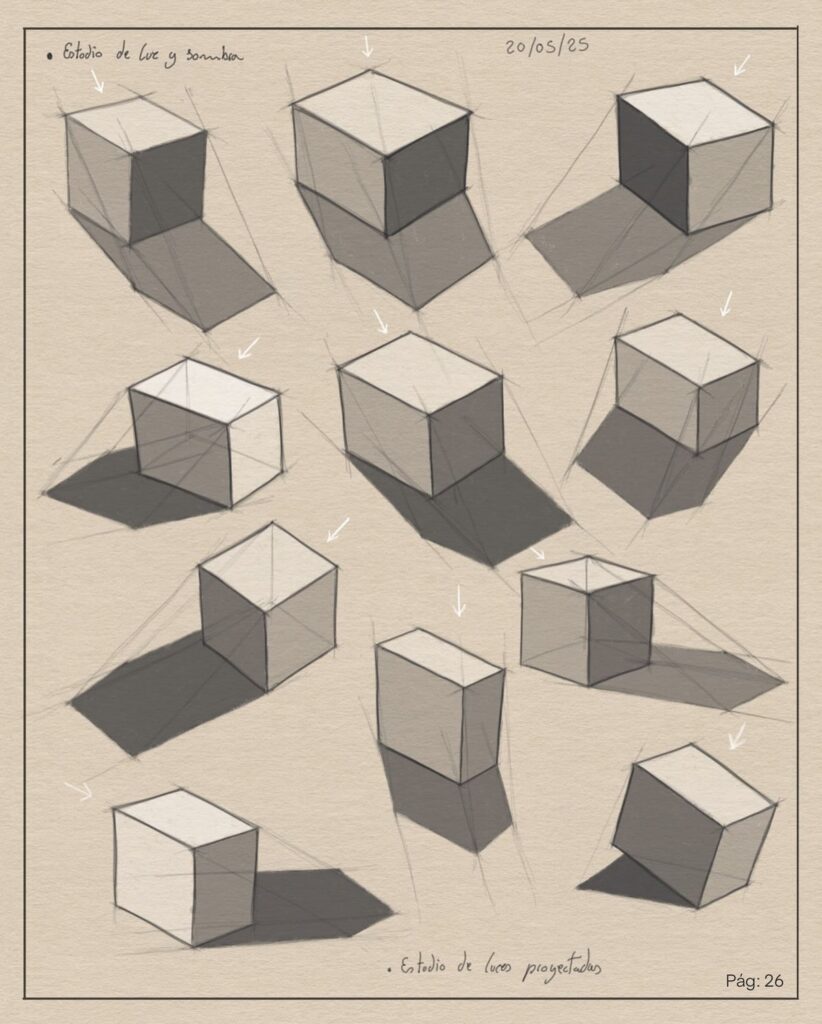

Understanding Light and Shadow: The Basics

Before we even touch a pencil to paper, let’s talk about the stars of our show: light and shadow. They are the dynamic duo that brings volume to your drawings. Without them, everything looks flat and lifeless. Imagine a world with no shadows – it would be impossible to tell how far away something is or what shape it truly has!

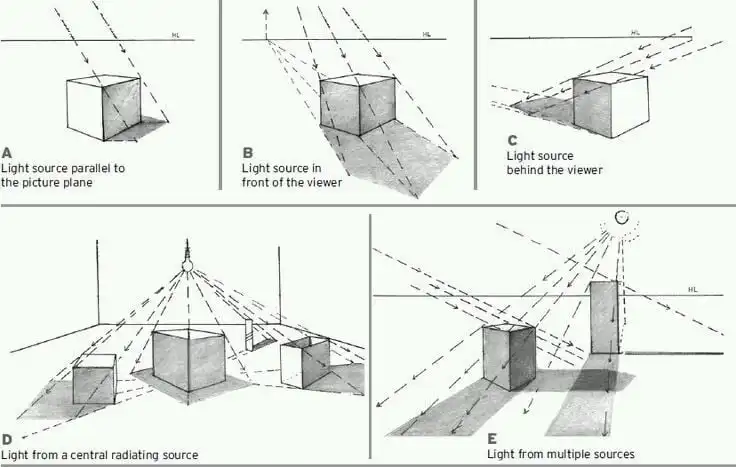

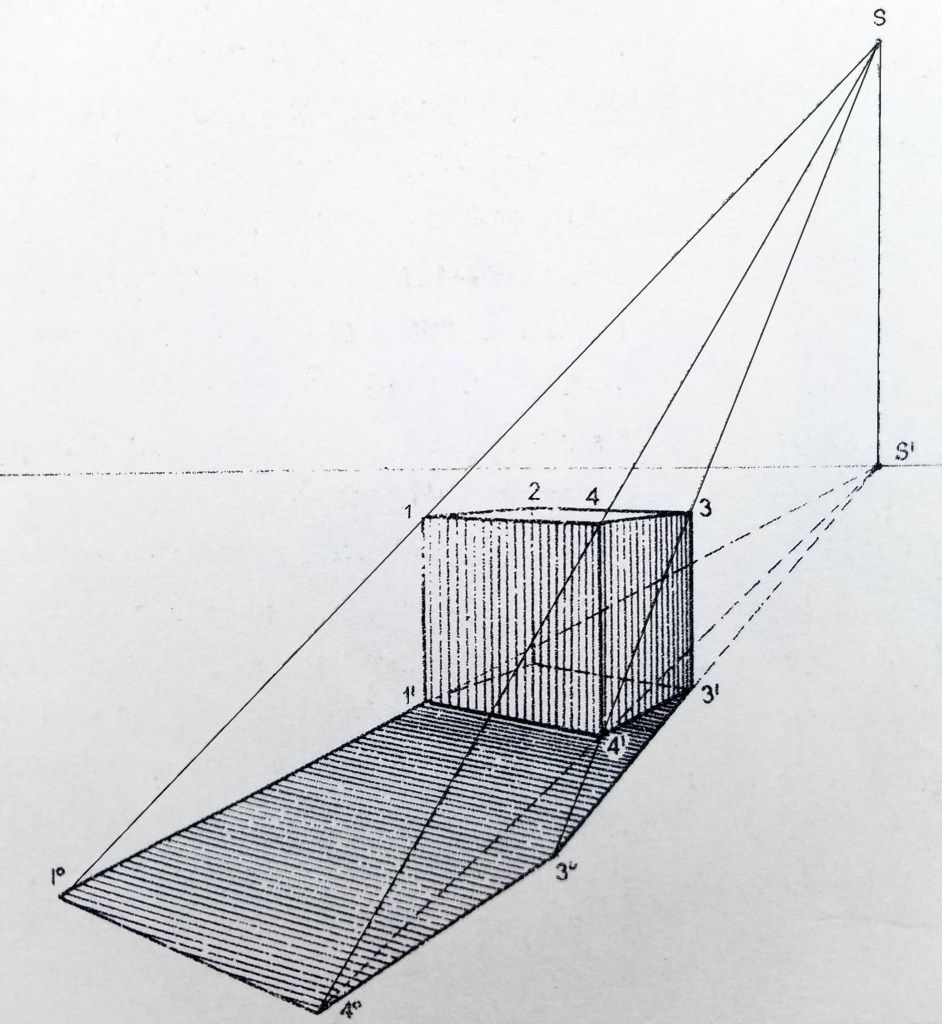

The first thing to grasp is the concept of a light source. This is where the light originates. It could be the sun, a lamp, or even a candle. The position and intensity of this light source dictate how light and shadow will fall on your object.

A strong, directional light source (like a single lamp) creates sharp, well-defined shadows, making it easier to see and draw. Diffused light (like a cloudy day or a room with many windows) creates softer, less distinct shadows, which can be trickier for beginners. For our cube, we’ll always aim for a single, clear light source.

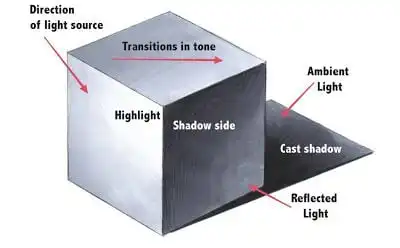

Now, let’s break down the different elements of light and shadow you’ll encounter on any three-dimensional object, especially our trusty cube:

- Highlight: This is the brightest point on the object, where the light source hits directly and reflects most intensely back to your eye. It’s often a small, bright spot.

- Midtone: These are the areas that receive light but aren’t directly facing the light source. They form a gradient between the highlight and the core shadow. On a cube, these are typically the planes that are angled away from the direct light.

- Core Shadow: This is the darkest part of the object itself. It’s the area where light cannot reach because the object’s form turns away from the light source. The edge of the core shadow, where light transitions to shadow, is called the “terminator line.”

- Reflected Light: This is a subtle but crucial detail. Light doesn’t just hit an object and stop. It bounces! Reflected light is ambient light bouncing off surrounding surfaces (like the table the cube sits on) and gently illuminating the shadow side of the object. It keeps the core shadow from looking like a flat, black hole.

- Cast Shadow: This is the shadow an object projects onto the surface it rests upon, or onto other objects nearby. The cast shadow is always darkest closest to the object and gets lighter and softer as it extends away. Its shape is determined by the object’s form and the light source’s direction.

- Occlusion Shadow: This is the absolute darkest part of a shadow, occurring where two surfaces meet and block out virtually all light. Think of the tiny sliver of shadow right where the base of the cube touches the table. It’s usually the darkest point in your entire drawing.

Understanding these elements is like learning the alphabet of shading. Once you know them, you can start to “read” the light and shadow on any object. For an artist, developing this eye for distinguishing different values (lightness and darkness) is as important as mastering perspective or proportions. If you’re interested in refining your observational skills further, exploring resources like learning proportions: how to draw the human figure for fashion illustration can provide a broader context on how foundational drawing principles translate across different subjects.

Gather Your Gear: What You’ll Need

You don’t need a fancy art studio or a huge budget to start learning how to shade a cube. In fact, some basic supplies are all you require. Think of it as a small investment in a massive skill upgrade!

Here’s a simple checklist of your essential tools:

- Pencils (and a Sharpener!): You’ll want a range of graphite pencils.

H Pencils (e.g., 2H, 4H): These are “hard” pencils, meaning they leave lighter marks and are good for initial sketches, guidelines, and very light tones. HB Pencil: This is your standard writing pencil, a good middle-ground for midtones. B Pencils (e.g., 2B, 4B, 6B, 8B):* These are “black” or “soft” pencils. They lay down darker, richer tones with less pressure and are essential for core shadows, cast shadows, and achieving deep darks. The higher the number, the softer and darker the lead.

- Paper: Any decent drawing paper will do.

Smooth Bristol Board: Great for detailed work and very smooth blending. Medium Tooth Sketch Paper: Offers a bit of texture for graphite to grab onto, which can be forgiving for beginners. Avoid paper that’s too rough, as it can make smooth blending difficult.

- Erasers: Don’t just think of erasers as tools for mistakes; they’re also for shaping light!

Kneaded Eraser: This squishy, pliable eraser is fantastic for lifting graphite, softening edges, and creating subtle highlights without damaging the paper. You can mold it into points for precise work. Plastic/Vinyl Eraser (e.g., Staedtler Mars Plastic): This is a clean-erasing workhorse for larger areas and stubborn marks.

- Blending Tools: While you can blend with your finger (though it leaves oils), dedicated tools give better results.

Tortillons or Paper Stumps: These are tightly rolled paper tools with pointed ends, perfect for smooth transitions and blending small areas. Cotton Swabs or Q-Tips: A readily available alternative for softer blending over larger areas. Soft Tissue or Cotton Ball:* Excellent for very broad, subtle blending.

- A Reference Cube (or Box): You don’t need a fancy geometric model. Any simple box will do – a cereal box, a tissue box, or even a small cardboard box you can tape together.

- A Single, Strong Light Source: A desk lamp with an adjustable neck is ideal. The goal is to create clear, distinct shadows. Avoid overhead room lights or multiple light sources, as they create confusing, overlapping shadows.

Having these tools ready means you can focus entirely on the drawing process itself. Each tool plays a specific role in achieving realistic shading, from establishing your initial lines to finessing the final subtle details.

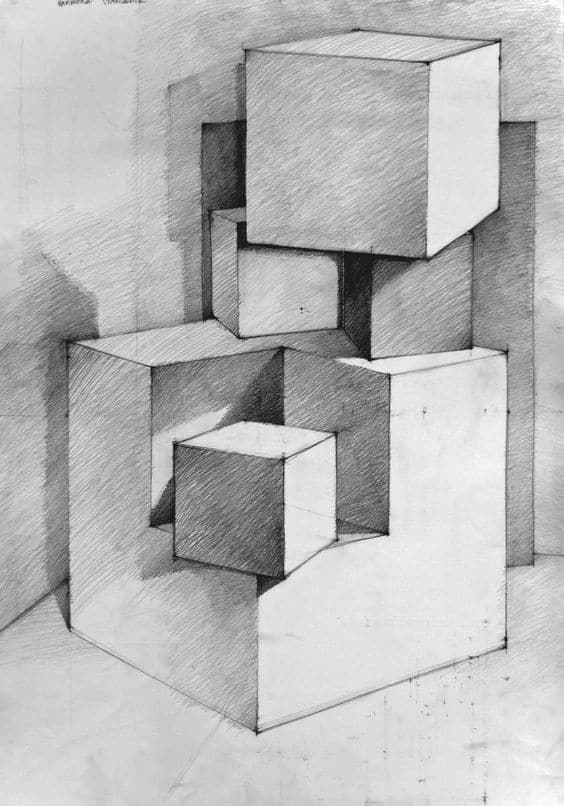

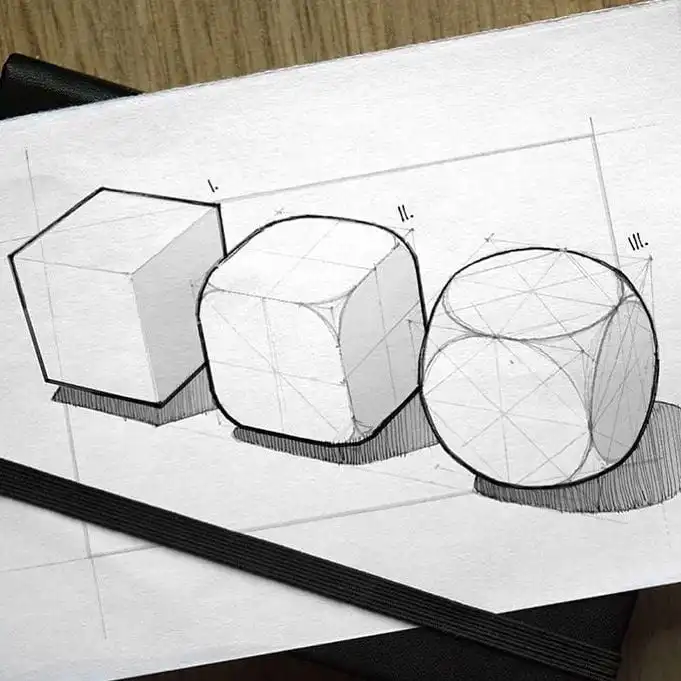

The Cube: Your Perfect Practice Partner

Why a cube, you ask? Because it’s the simplest geometric form, made up of flat planes and sharp edges. This makes it an ideal subject for understanding how light behaves on distinct surfaces. Each face of the cube presents a clear decision point for how much light it receives, making the principles of shading very evident. If you can shade a cube convincingly, you’ve got a solid grasp on how light defines form.

Setting Up Your Reference:

1. Find Your Cube: Grab that box! A plain, light-colored box is best as it won’t distract you with patterns or complex colors.

2. Choose Your Stage: Place your cube on a flat, neutral-colored surface (a white or grey sheet of paper or cloth works great) against a plain background. This ensures any reflected light or cast shadows are clearly visible and not confused by busy surroundings.

3. Position Your Light Source: This is crucial. Place your single desk lamp to one side, slightly above and in front of the cube. The goal is to create a clear division of light and shadow: One face of the cube should be clearly lit. Another face should be in shadow. The top face should also show some degree of light or shadow depending on the light’s height. A distinct cast shadow should be visible on the surface that the cube rests on.

4. Eye Level: Position yourself so you are looking at the cube roughly at eye level. This helps simplify the perspective and prevents extreme foreshortening, making it easier to focus on shading.

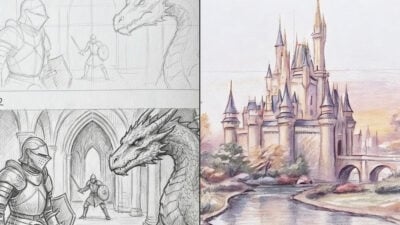

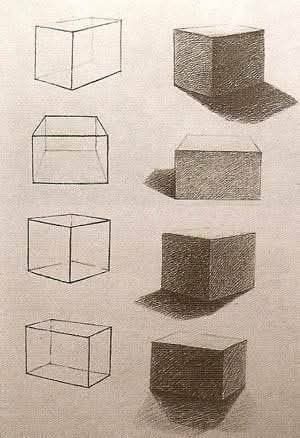

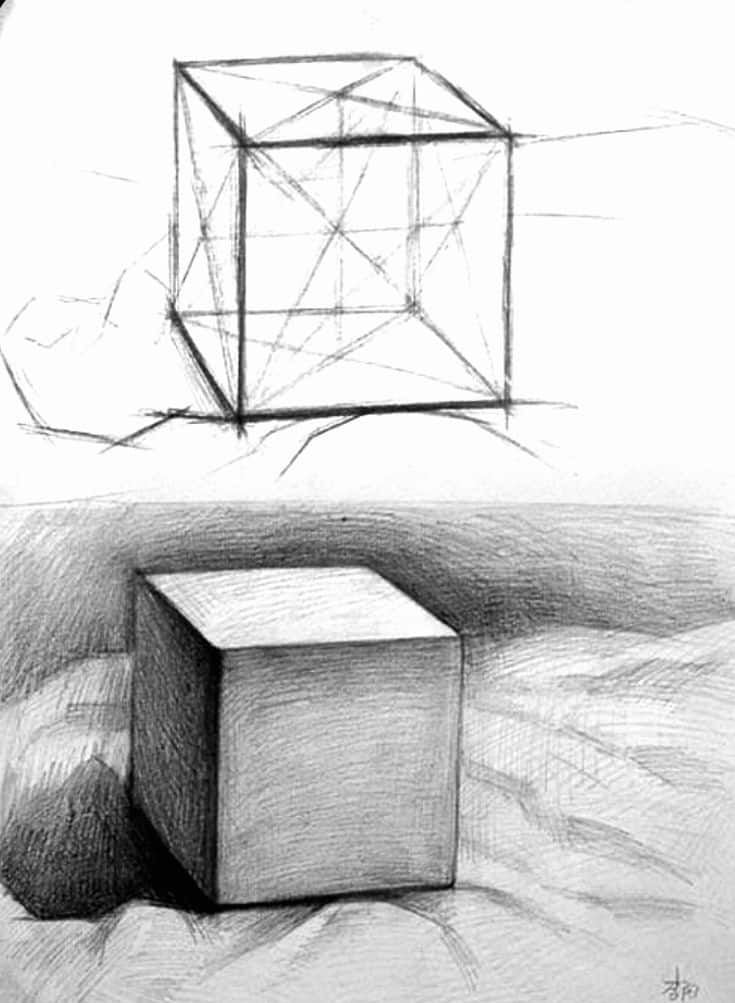

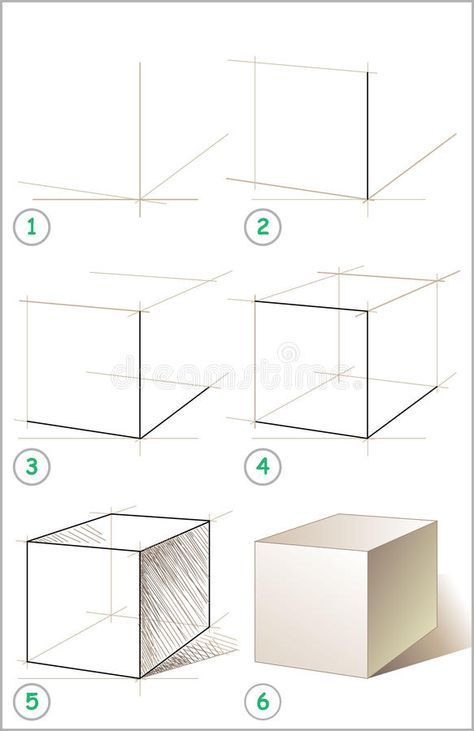

Initial Sketch: Drawing the Cube in Perspective

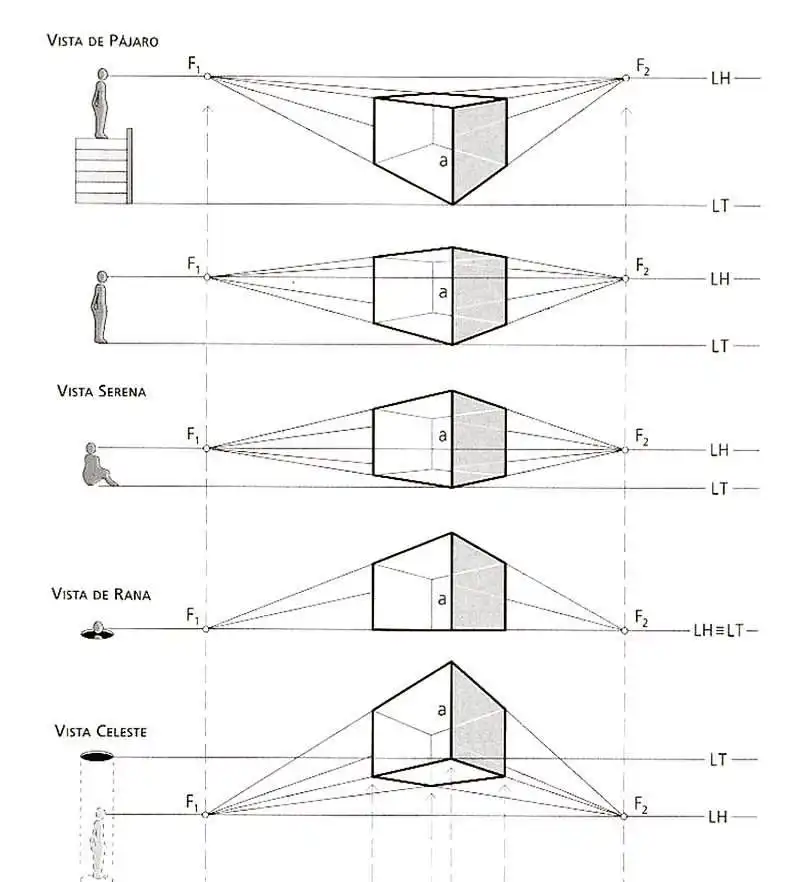

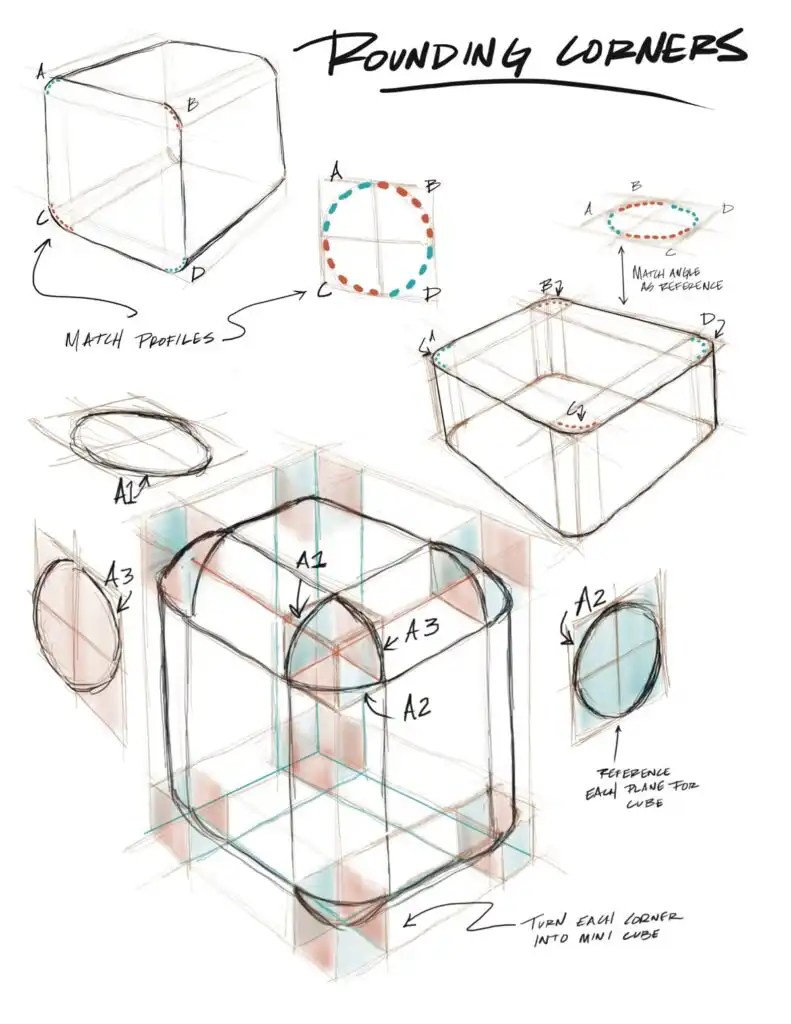

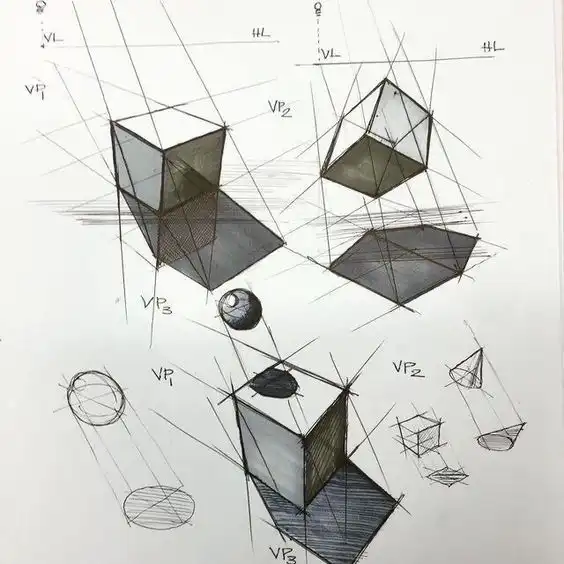

Before you can shade it, you need to draw your cube accurately. This involves a basic understanding of perspective. Don’t worry, we’re not talking about complex cityscapes here, just enough to make your cube look three-dimensional.

1. Light Touch: Start with your lightest pencil (2H or HB) and draw very lightly. These are just guidelines.

2. Establish the Front Edge: Find the vertical edge of the cube closest to you. Draw this line first. This will be your anchor.

3. Vanishing Points (Implied): Imagine lines receding from the top and bottom of your front edge. They will appear to converge at a “vanishing point” on your eye-level line (horizon line). For a simple cube, you’ll typically see two vanishing points for a corner-on view, or one for a face-on view. Don’t worry about drawing precise vanishing points; just ensure your parallel lines appear to recede and converge.

4. Draw the Receding Edges: From the top and bottom of your front edge, draw light lines angling upwards and downwards, reflecting how the cube’s edges recede into the distance.

5. Complete the Visible Faces: Draw the vertical edges that define the back corners of the visible faces. Then connect these to complete the top, front, and side planes of your cube.

6. Refine Your Lines: Once you’re happy with the basic shape, you can gently darken the outlines of your cube. Remember, these lines won’t exist in the final shaded drawing; they’re just there to define the form. The “lines” in a finished drawing are actually edges created by the contrast between different values of light and shadow.

A solid initial drawing sets the stage for effective shading. If your cube isn’t drawn well, even the best shading won’t make it look right. Practice drawing cubes from different angles, and you’ll quickly improve your spatial reasoning and perspective skills, which are vital for all drawing, just as exploring action pose drawing ideas requires a strong grasp of underlying form.

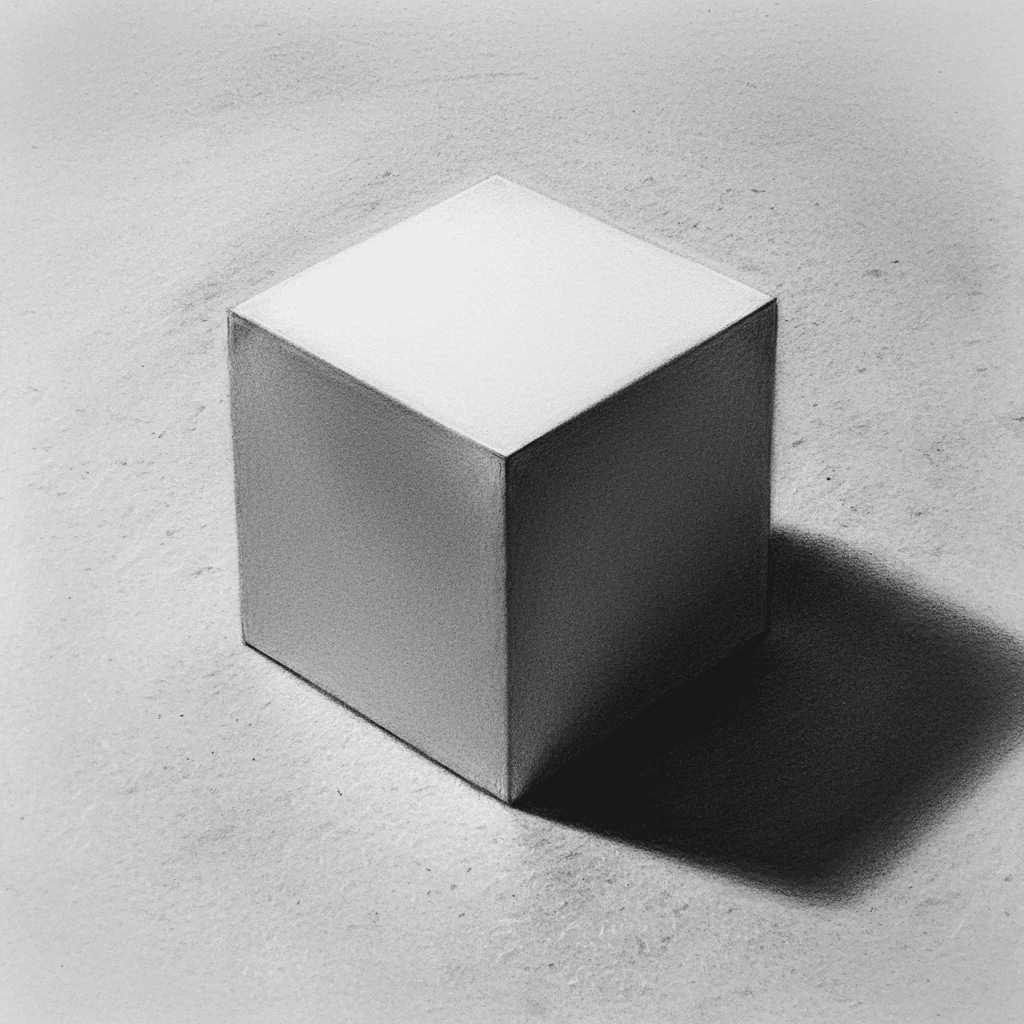

Deconstructing Light on a Cube: The Six Essential Values

Now, let’s get into the nitty-gritty of how light interacts with your cube. This is where those terms we learned earlier come to life. On a simple cube, you’ll typically have three visible faces, each receiving a different amount of light, plus the surrounding shadows. We’ll identify six key value areas.

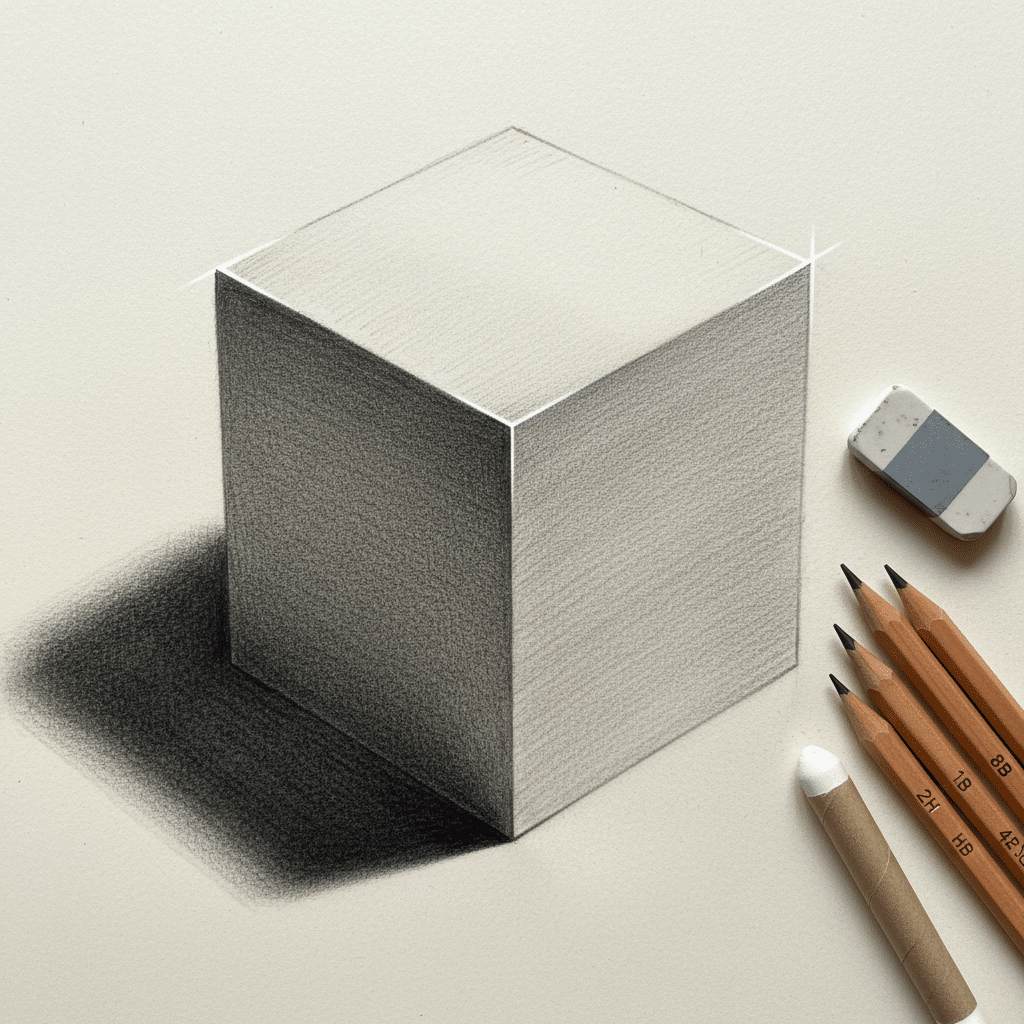

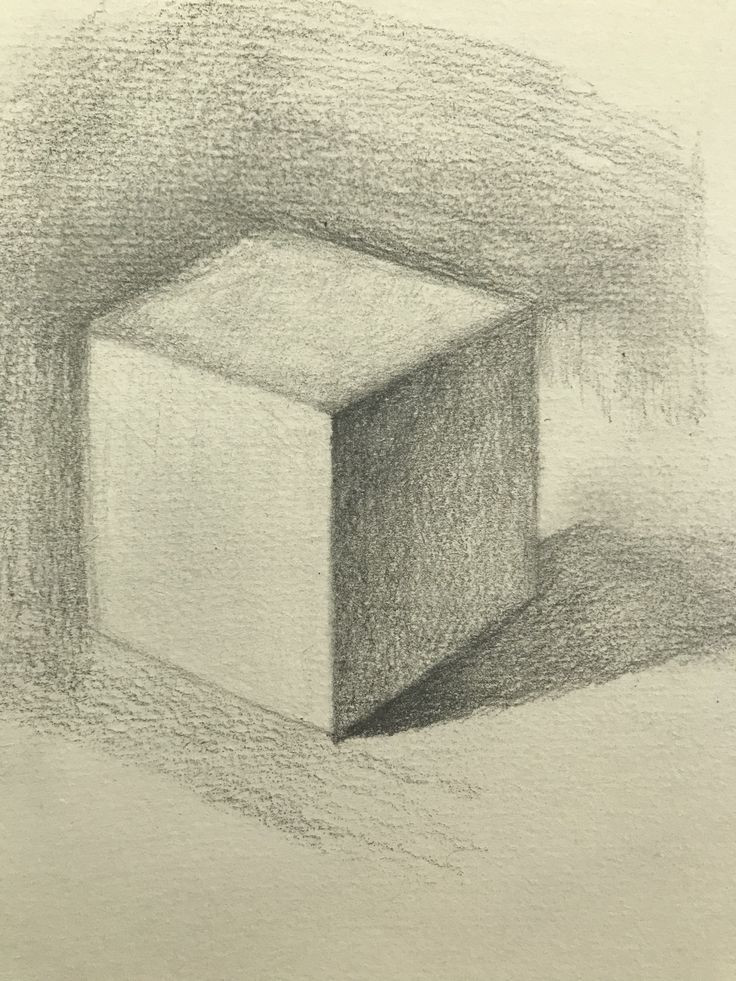

1. The Highlight

This is the brightest spot on your cube. It will be on the face most directly exposed to the light source. On a cube, this isn’t usually a single tiny dot like on a sphere, but rather the entire plane that is brightest. If your light source is strong and directional, one entire face might be very brightly lit. Use your kneaded eraser to lift any graphite that might have strayed into this area, keeping it pristine white (or the color of your paper). This is the area you’ll often leave as the pure white of your paper.

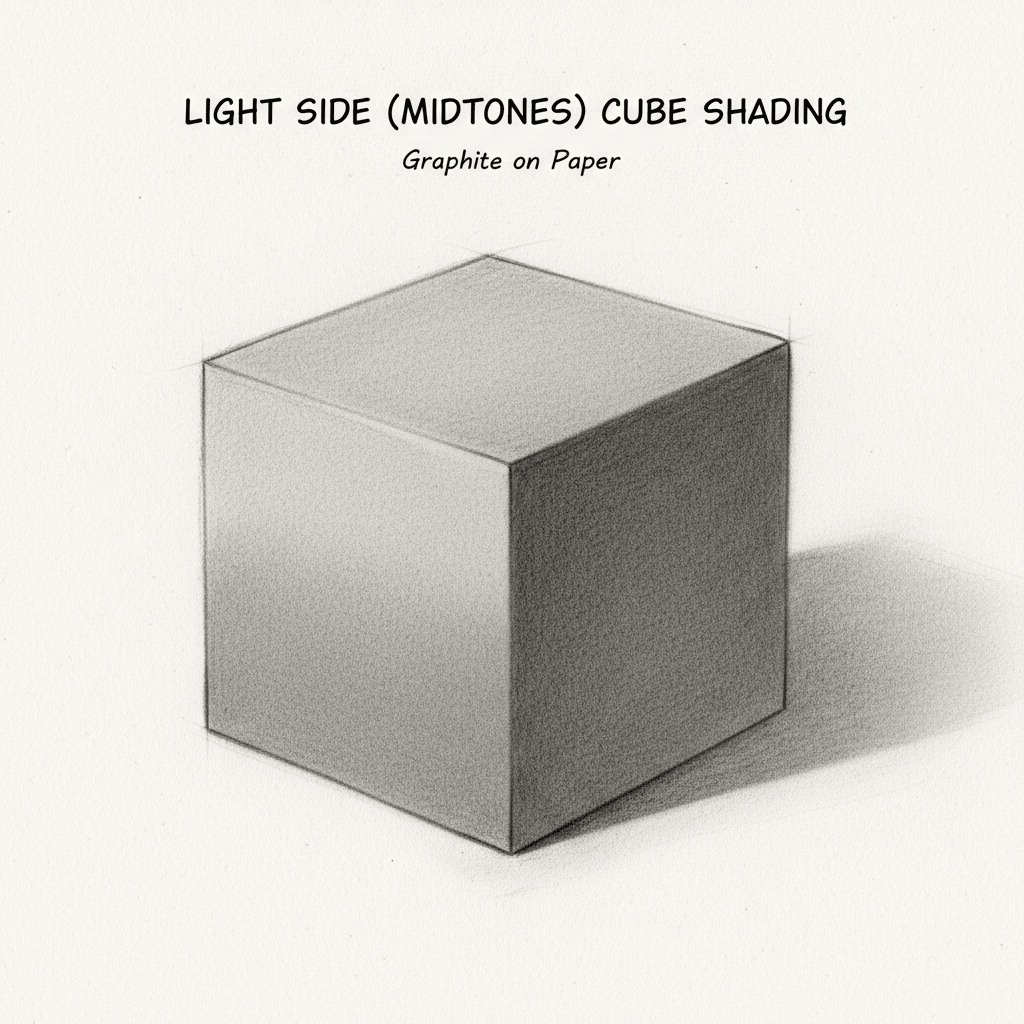

2. The Light Side (Midtones)

This refers to any other face of the cube that is receiving direct light but is angled more away from the primary light source than the highlight face. It will be lighter than the shadow side but darker than the highlight. You’ll use your lighter pencils (HB, 2B) for these areas, applying a soft, even tone. Think of it as a subtle gradient across the entire plane, slightly darker than the brightest face.

3. The Core Shadow

This is the darkest area on the cube itself. It’s the face (or faces) that are completely turned away from the light source. Here, you’ll use your darker B pencils (4B, 6B) to lay down a rich, deep tone. The edge where the light side transitions to the core shadow is called the “terminator line.” This line should be relatively sharp on a cube because of its angular nature, indicating the abrupt change in plane.

4. Reflected Light

Look closely at the shadowed face of your cube. Is it uniformly black? Probably not. You’ll likely see a subtle glow along the bottom edge or the edge facing the table. This is reflected light bouncing up from the table surface. This area should be lighter than the core shadow, but still part of the overall shadow side. Use a lighter touch with a B pencil or gently lift a little graphite with a kneaded eraser from the core shadow to reveal this subtle effect. It adds so much realism and prevents the cube from looking cut out.

5. The Occlusion Shadow

Where the base of the cube meets the surface it’s sitting on, you’ll find the absolute darkest point in your entire drawing. This is the occlusion shadow. It’s so dark because almost no light can penetrate this tiny crevice. This is where you might use your darkest pencil (6B or 8B) and press a little harder. This dark line anchors the cube firmly to the surface, making it look grounded.

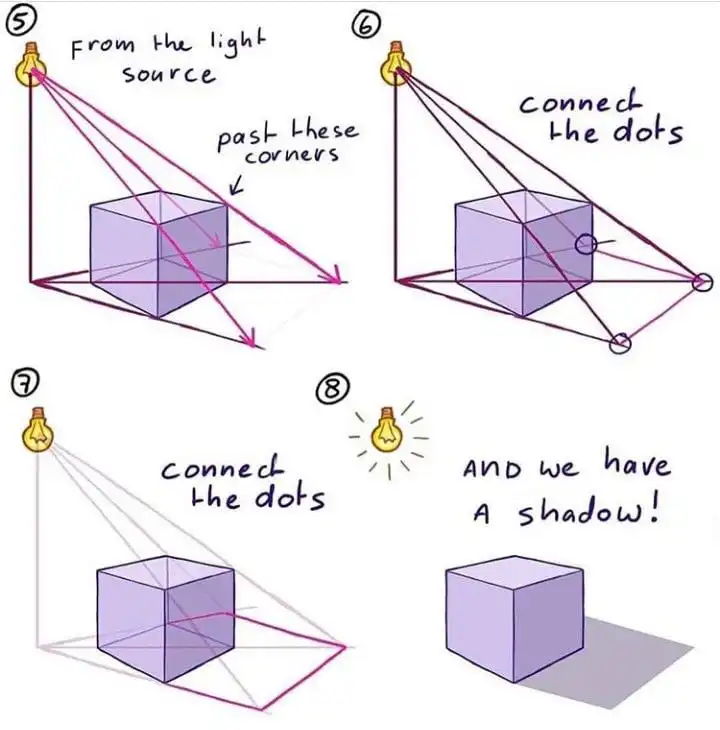

6. The Cast Shadow

The cast shadow is the shadow the cube throws onto the table or background. Its shape will mimic the cube’s form, extending away from the light source. The cast shadow is usually darkest closest to the cube (especially near the occlusion shadow) and gradually gets lighter and softer as it moves further away from the object. Its edges also tend to soften with distance. Pay attention to its shape – it’s part of the cube’s presence in space. Don’t make it a uniform dark blob; it has its own subtle value shifts.

By breaking down the cube into these six distinct value areas, you create a roadmap for your shading. It’s not just about making things dark or light; it’s about understanding why they are dark or light based on the interaction with the light source.

Step-by-Step Shading Process: Bringing Your Cube to Life

Now that you understand the different components of light and shadow, let’s put it all together. This process is about building up your tones gradually, from light to dark. Patience is your best friend here!

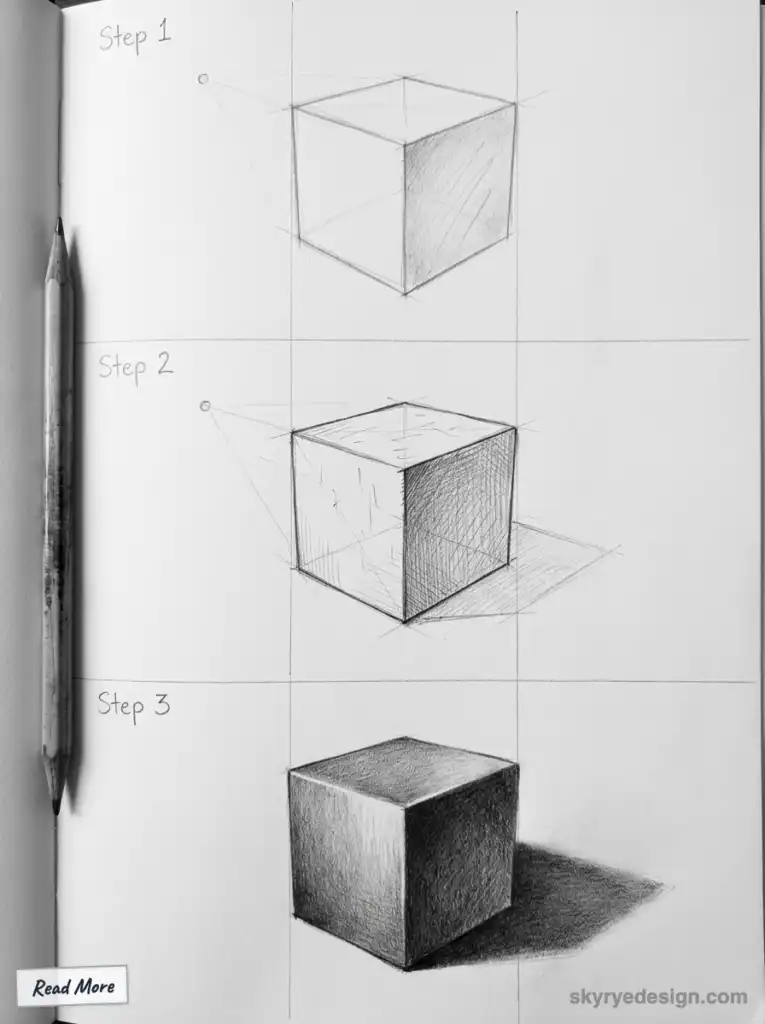

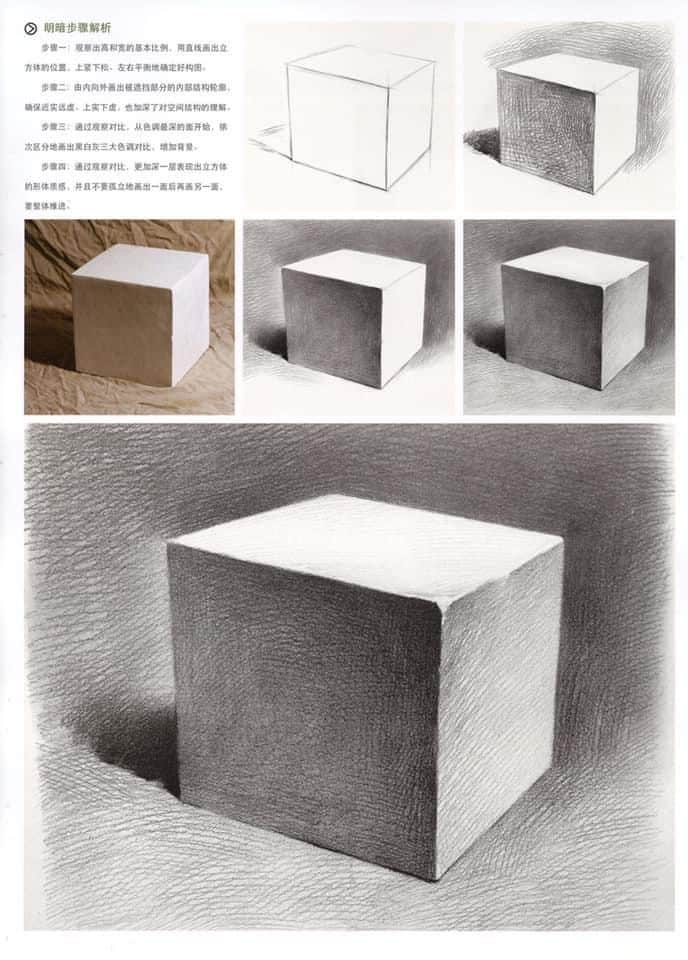

Step 1: Outline and Light Source

Start with your accurately drawn cube outline. Use a light HB or 2H pencil. Before you do anything else, identify your light source on your reference and mentally (or lightly) mark its direction on your drawing. This is your guiding star for all subsequent shading.

Step 2: Blocking in Basic Values

Using an HB or 2B pencil, lightly block in the main areas of light and shadow. Don’t press hard. Just establish which faces are generally light and which are generally dark. This isn’t about detail yet; it’s about separating the major planes. Think of it as laying down a base coat.

Step 3: Defining the Core Shadow

Now, focus on the darkest areas on the cube itself. Using a 4B or 6B pencil, begin to build up the tone on the face(s) that are in core shadow. Apply strokes in a consistent direction (e.g., small circular motions or parallel lines) and gradually layer the graphite. Don’t go for full darkness immediately; build it up. Define the terminator line where the light side meets the core shadow.

Step 4: Adding Reflected Light

Before you make the core shadow too dark, remember the reflected light! Gently lighten the area along the edge of the core shadow closest to the surface it rests on. You can do this by using less pressure with your B pencil in that area, or by gently tapping a kneaded eraser to lift a tiny bit of graphite if you went too dark. This subtle touch will make a huge difference in making your cube look volumetric.

Step 5: Developing Midtones

Shift your attention to the light sides of the cube. Using your HB or 2B pencil, start building up the midtones. One light face might be slightly darker than another, depending on its angle to the light. Create a smooth, even tone across these planes. If you have a highlight face that is pure white, ensure it remains untouched.

Step 6: Rendering the Cast Shadow

Now, let’s tackle the shadow the cube casts. Using a 4B or 6B pencil, begin to lay down the shape of the cast shadow. Remember, it’s darkest closest to the cube (where the occlusion shadow is) and gradually lightens as it moves away. Start dark near the cube’s base, then ease off the pressure as you extend the shadow outwards. Pay attention to its shape and how it defines the space around the cube.

Step 7: Blending and Smoothing

Once your values are laid down, it’s time to blend. Use your tortillon, paper stump, or cotton swab. Gently rub the graphite in circular motions or in the direction of your strokes to smooth out transitions. Be careful not to over-blend; you still want to retain some subtle texture. Blend the light sides, the core shadow, and especially the cast shadow to create smooth gradients. The goal is to eliminate harsh lines where they shouldn’t be, creating a seamless flow of light and shadow.

Step 8: Refining Details and Edges

This is the cleanup and polish stage.

- Crisp Edges: Use your plastic eraser to sharpen any edges that need to be defined, especially where the cube meets the background or where the cast shadow has a clear boundary.

- Highlights: Use your kneaded eraser, molded to a point, to carefully lift graphite and create bright, crisp highlights on the most illuminated plane.

- Darkest Darks: Go back with your darkest pencil (6B or 8B) and reinforce the very darkest parts of the occlusion shadow and the core shadow to add punch and contrast.

- Subtle Textures: If your paper has some tooth, you might see subtle texture. Embrace it, or blend a little more for a smoother look if that’s your preference.

- Step Back: Periodically step away from your drawing to get a fresh perspective. Your eyes can get used to mistakes when you’re too close.

This step-by-step process builds complexity gradually, allowing you to focus on one aspect at a time. It’s a methodical approach that yields impressive results.

Common Mistakes to Avoid (and How to Fix Them)

Even seasoned artists make mistakes, especially when learning new techniques. The key is to recognize them and know how to course-correct. Here are some common pitfalls when shading a cube and how to tackle them:

- Flat Shading (Not Enough Value Range):

Mistake: Your cube looks grey all over, without distinct darks and lights. You’re afraid to go dark enough. Fix: Push your values! Use your darkest B pencils (6B, 8B) for the core shadow and occlusion shadow. Conversely, make sure your highlight is truly the brightest area. Create a mental or actual value scale (a strip from white to black in 5-7 steps) to compare against your drawing.

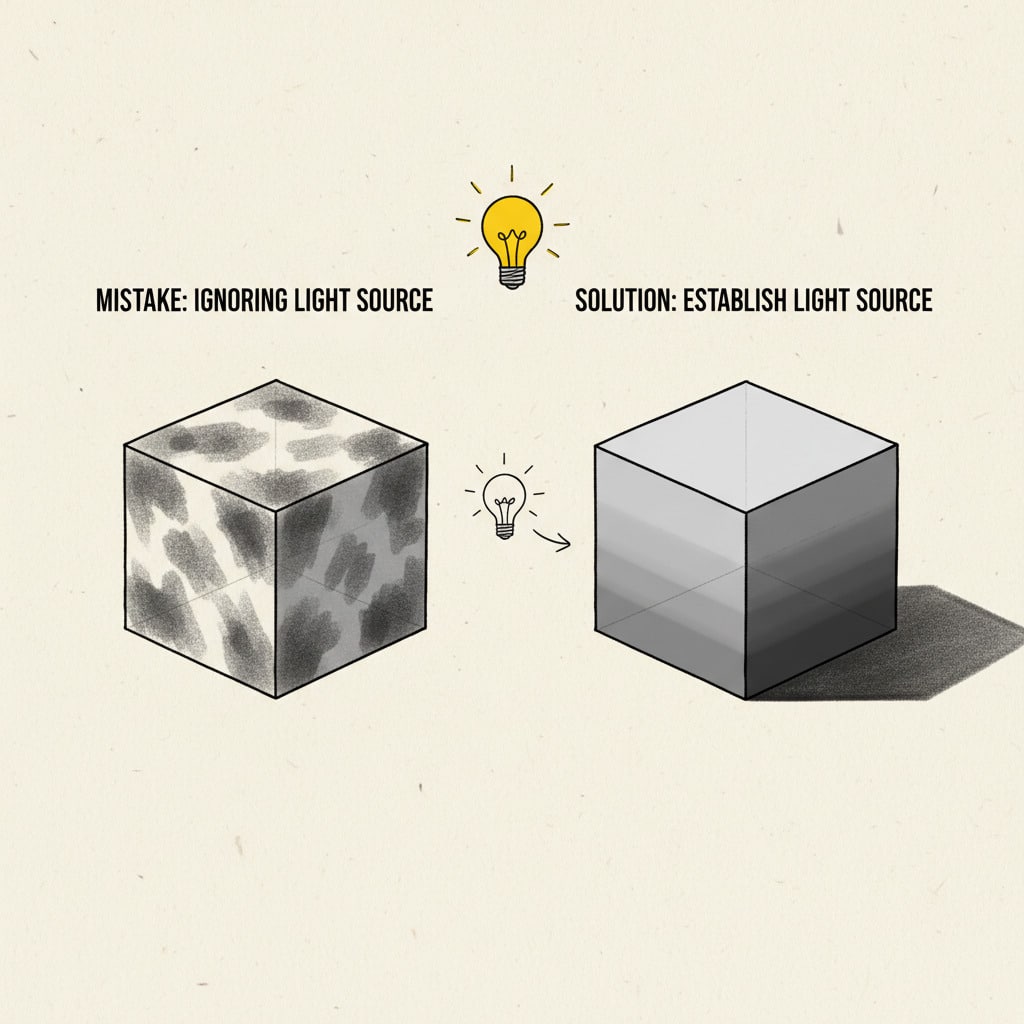

- Undefined Light Source:

Mistake: Shadows and highlights seem random, not following a clear direction. Fix: Go back to your reference cube and lamp. Stare at it. Really understand where the light is coming from. If your setup isn’t clear, adjust your lamp until you have distinct light and shadow areas. Stick to one light source!

- Ignoring Reflected Light:

Mistake: The shadow side of your cube looks like a flat, lifeless black shape. Fix: Remember to add that subtle lift of reflected light. Gently erase or apply less pressure along the shadowed edge closest to the surface. It’s a game-changer for realism.

- Harsh Edges in Shadows:

Mistake: Your cast shadow or core shadow has a sharp, hard outline that doesn’t look natural. Fix: Blend! Use your paper stump, tortillon, or cotton swab to soften the edges, especially the outer edges of the cast shadow as it moves away from the cube. On the cube itself, while the terminator line can be crisp, the overall shadow shouldn’t have a harsh cut-out look.

- Over-Blending:

Mistake: You’ve blended so much that all your hard work defining different planes is gone, resulting in a muddy, undefined mess. Fix: Blend strategically. Focus on smoothing transitions, not erasing definition. Sometimes, a light, consistent pencil stroke in one direction creates a beautiful texture that blending might destroy. Learn when to stop!

- Incorrect Cast Shadow Shape or Intensity:

Mistake: The cast shadow doesn’t look like it belongs to the cube or is uniformly dark. Fix: Observe your reference closely. The cast shadow’s shape is crucial; it follows the light direction and the form of the object. Also, remember its value gradient: darkest near the object, lighter as it extends. For more foundational drawing assistance, remember that resources like eye drawing tutorials for your skill emphasize the importance of observation and precision, skills directly applicable to understanding shadow shapes.

Recognizing these issues and having strategies to correct them will accelerate your learning process. Don’t be afraid to make mistakes; they’re just opportunities to learn.

- 0shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest0

- Twitter0

- Reddit0