In January 2026, Craig died. He was 54 years old, and his tusks nearly scraped the ground when he walked—each one weighing over 100 pounds. Millions of people who’d never set foot in Kenya’s Amboseli National Park mourned him. A wild elephant, gone.

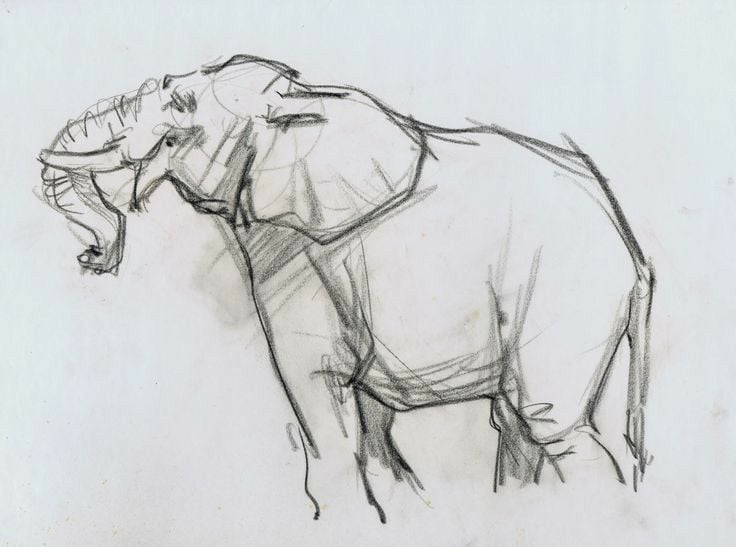

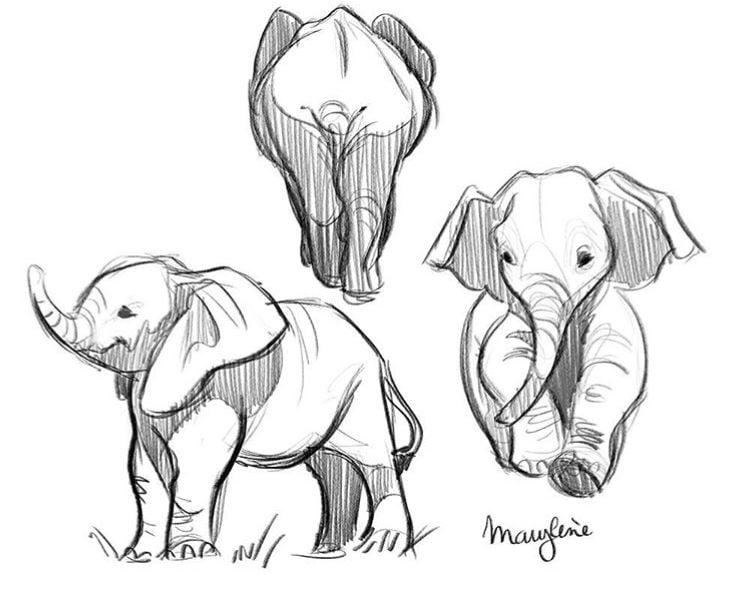

I think about Craig when I draw elephants. There’s something about putting pencil to paper that forces you to really look at an animal—the way the skin folds, how small the eyes actually are, the specific curve of a tusk. It’s observation as a form of respect.

If you’ve tried to learn how to draw an elephant before, you’ve probably followed a tutorial that gave you a generic cartoon: circle for a head, two big ears, done. That’s fine for kids. But you’re here because you want something that actually looks like an elephant.

- Before You Draw: African vs. Asian Elephants

- What You'll Need (And Why It Matters)

- Step-by-Step: Drawing an African Elephant

- The Hard Part: Drawing Elephant Skin Texture

- 6 Mistakes That Ruin Elephant Drawings (And How to Fix Them)

- Taking It Further: Poses, Babies, and Herds

- FAQ: Your Elephant Drawing Questions, Answered

- Now Go Draw One

So that’s what we’re doing. You’ll learn the anatomical differences between African and Asian elephants (yes, it matters). You’ll master the texture that makes elephant skin so distinctive. And you’ll watch me make mistakes in real time—because that’s how drawing actually works.

Let’s start with the most important question most tutorials skip entirely.

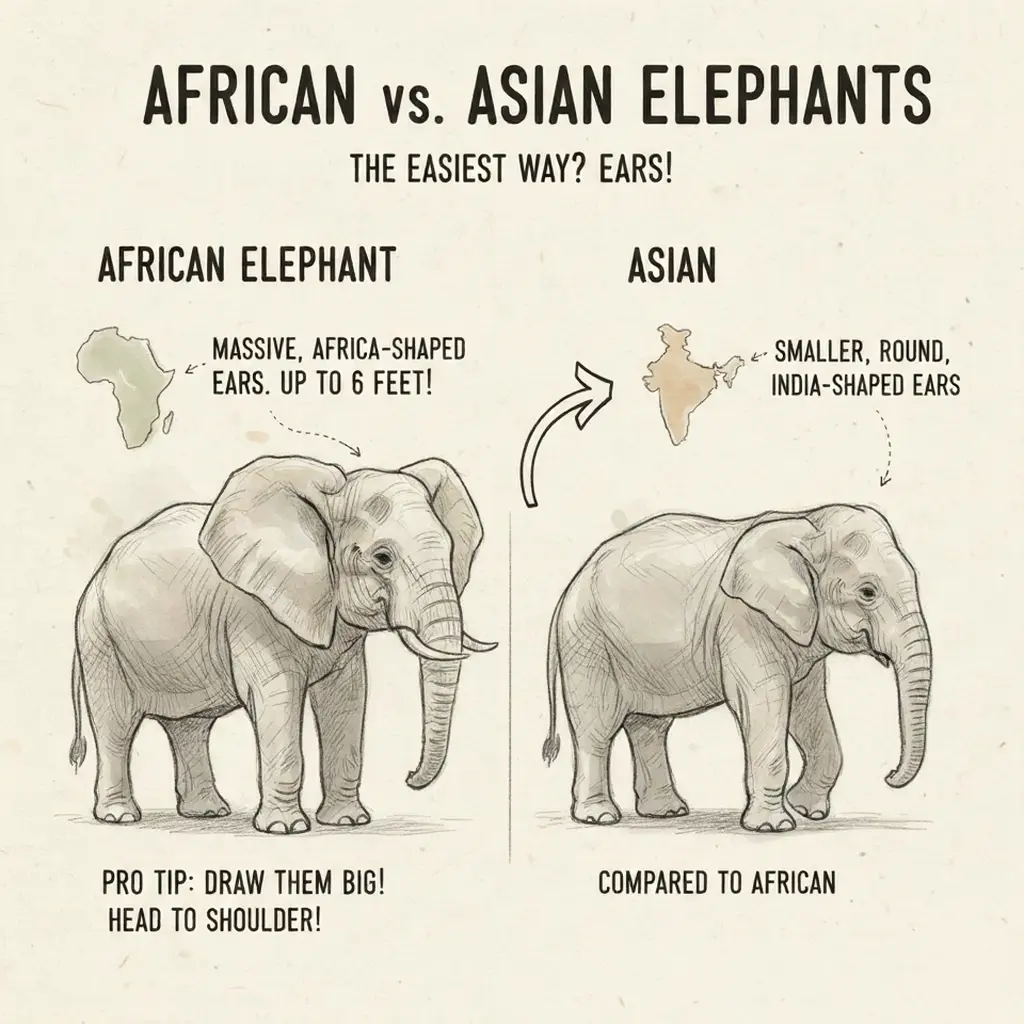

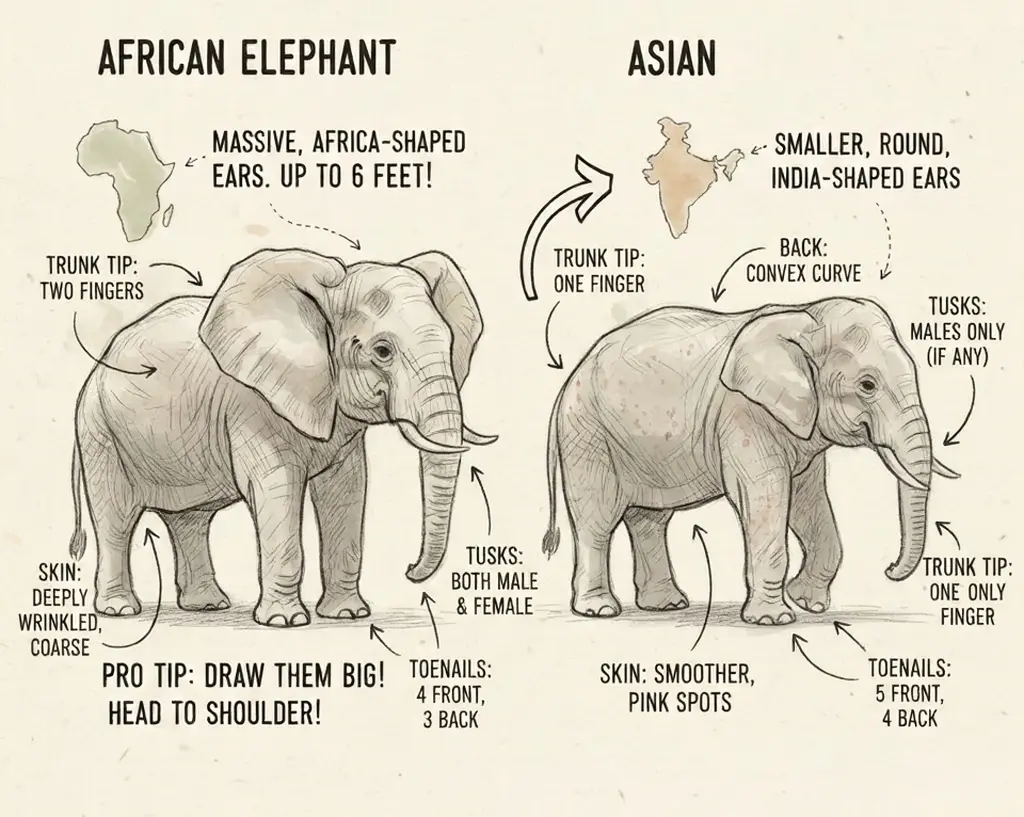

Before You Draw: African vs. Asian Elephants

Here’s a question that’ll change how you draw elephants forever: which one are you actually drawing?

Most tutorials skip this entirely. They teach you a generic elephant—some hybrid that doesn’t really exist. But African and Asian elephants are as different as lions and tigers. Get the details wrong, and anyone who’s seen a nature documentary will sense something’s off, even if they can’t explain why.

The Ears Tell the Story

The easiest way to spot the difference? Ears. African elephant ears are massive—up to six feet long—and shaped roughly like the African continent itself. They billow outward like sails. Asian elephant ears are smaller, rounder, and often described as shaped like India.

In my experience, beginners consistently draw African elephant ears too small. They look at that giant flap and think, “That can’t be right.” It is. When you’re sketching an African elephant, let those ears extend from the top of the head all the way down to the shoulder. It’ll feel exaggerated. It’s not.

Head Shape and the “Double Dome”

Look at an elephant’s forehead in profile. African elephants have a single, smoothly rounded dome. Asian elephants have two distinct humps with a visible dip running down the center—like a subtle M-shape.

This difference affects your entire silhouette. Miss it, and your Asian elephant will read as African (or worse, as nothing in particular).

The Details That Matter

A few more differences worth memorizing:

- Trunk tip: African elephants have two finger-like protrusions; Asian elephants have one

- Tusks: Both male and female African elephants typically grow tusks; only some male Asian elephants do

- Back shape: African = concave dip (saddle-back); Asian = convex curve

- Skin: African = deeply wrinkled, coarse; Asian = smoother with pink depigmentation spots

- Toenails: African = 4 front, 3 back; Asian = 5 front, 4 back

Wildlife illustrator Terryl Whitlatch—who designed creatures for Star Wars and Jumanji—spends entire chapters on these distinctions in her Gnomon Workshop tutorials. If it matters to a professional creature designer, it matters to your sketchbook.

One actionable tip: Before you start any elephant drawing, spend 30 seconds deciding: African or Asian? Then pull reference photos of that specific species. Your drawing will thank you.

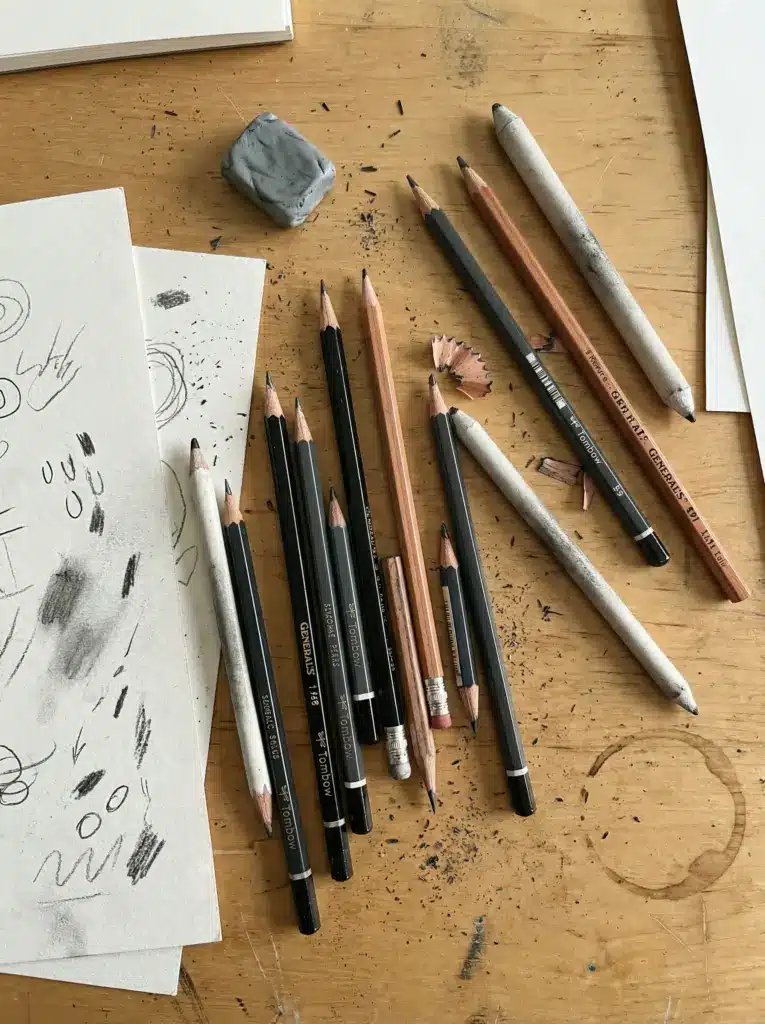

What You’ll Need (And Why It Matters)

You don’t need much. That’s the good news.

I’ve drawn elephants with a single No. 2 pencil from a hotel room desk. It worked. But the right tools make texture easier—and elephant skin is all about texture.

The Essentials

Here’s what I actually use:

- HB pencil — for light sketching and shapes you’ll erase later

- 2B pencil — your workhorse for defining forms and medium shading

- 4B or 6B pencil — the dark stuff: deep wrinkles, shadows under the belly, the inside of the ear

- Kneaded eraser — this is non-negotiable. You’ll lift graphite to create highlights on the trunk and forehead. A regular pink eraser won’t cut it.

- Blending stump or tissue — for smoothing base tones before you add texture

- Sketch paper — nothing fancy. Strathmore 400 series (around $8 for 24 sheets) handles erasing well without pilling.

Optional Upgrades

If you’re serious about realism, a graphite powder speeds up large tonal areas—I use General’s Powdered Graphite, about $6 on Amazon. An embossing tool (or even a dried-out ballpoint pen) lets you indent white lines into the paper before shading. Those lines stay white no matter how much graphite you layer over them. Perfect for bright highlights on tusks.

One tip: Keep your pencils sharp. Dull points make muddy texture. I sharpen between almost every section.

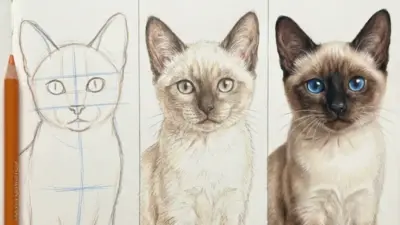

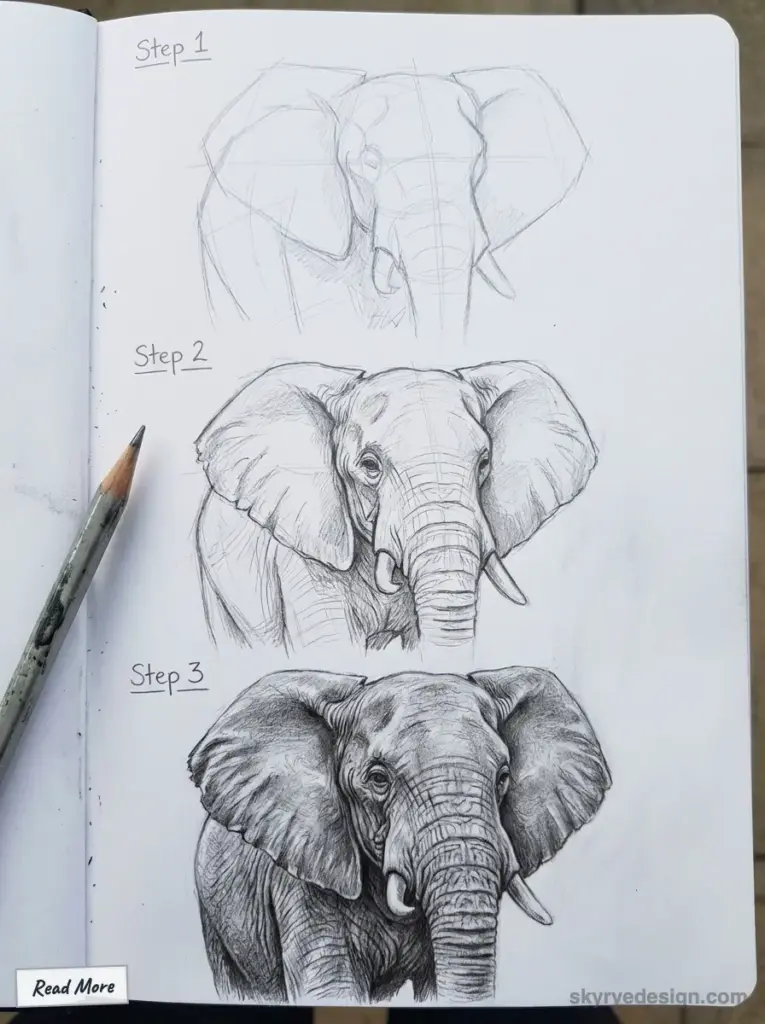

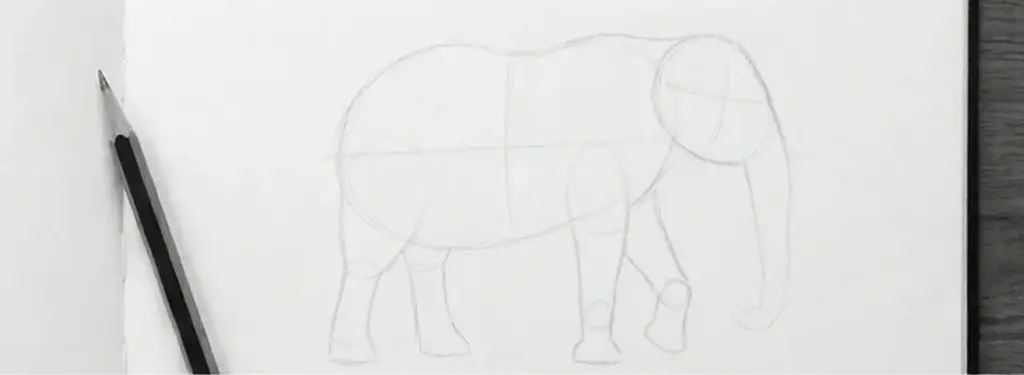

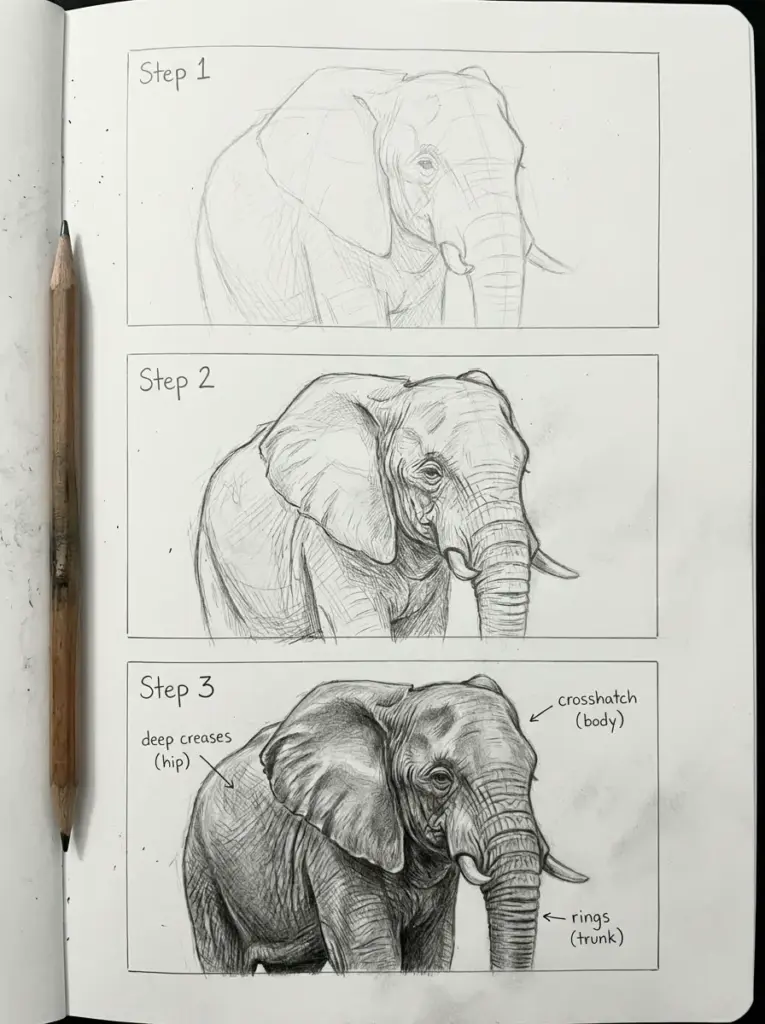

Step-by-Step: Drawing an African Elephant

Alright. Pencil sharpened, reference photo pulled up, paper ready. Let’s draw.

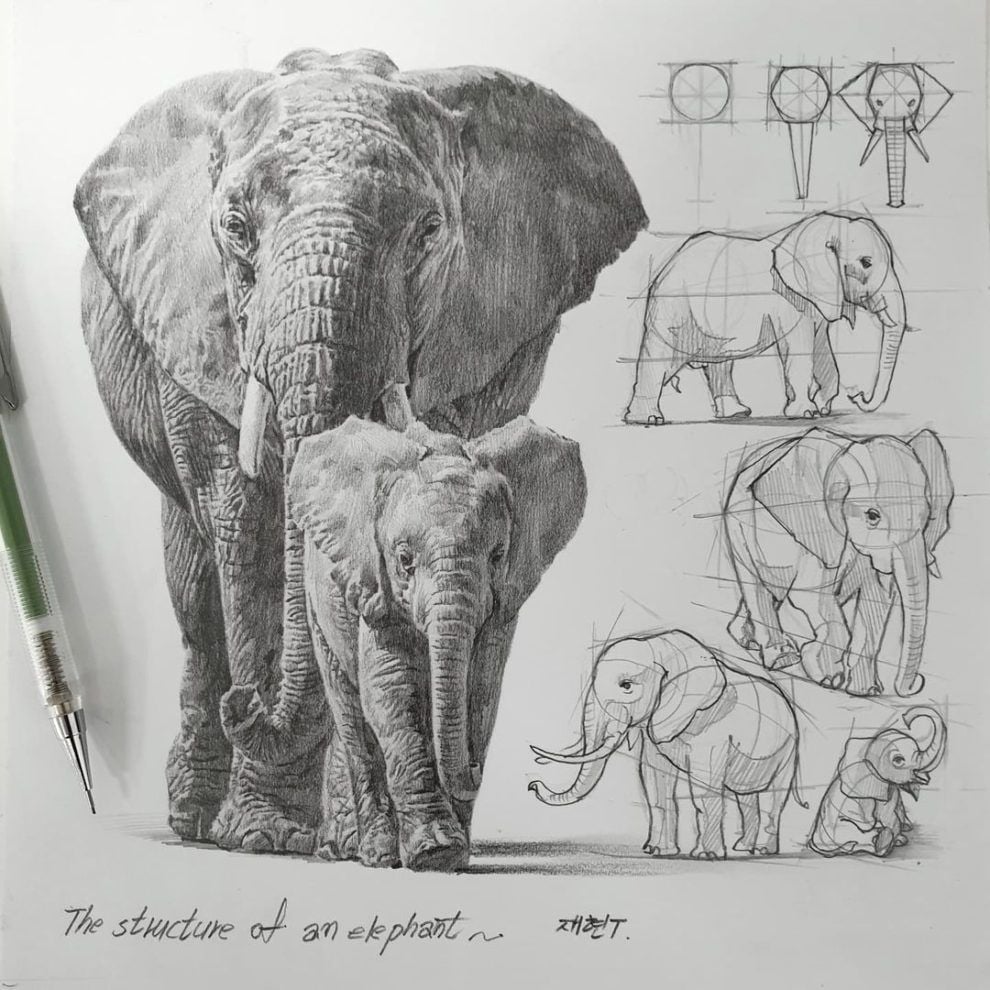

I’m walking you through an African elephant in side profile—it’s the clearest way to learn the proportions before you attempt trickier angles. Once you nail this, three-quarter views and dynamic poses become much easier.

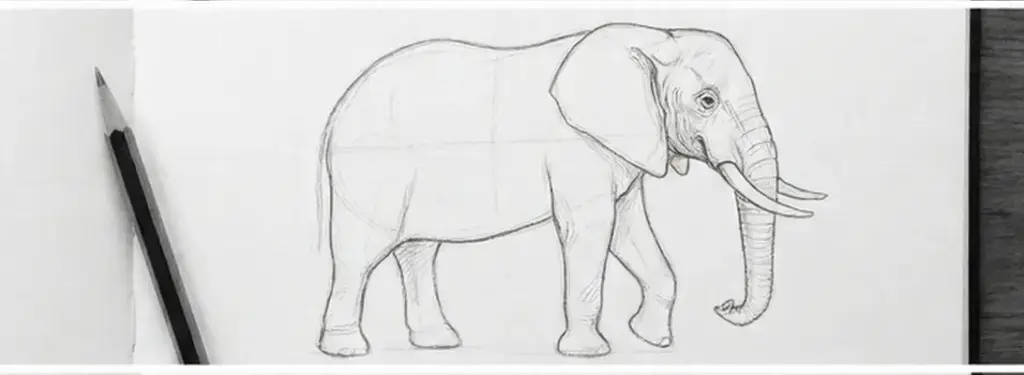

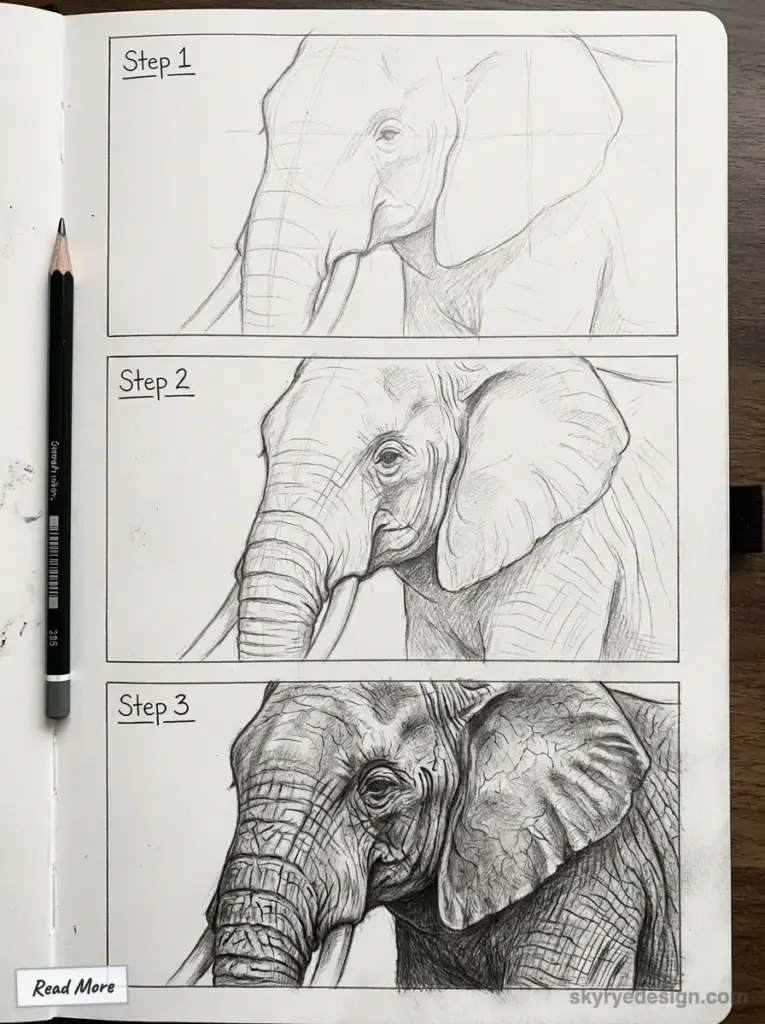

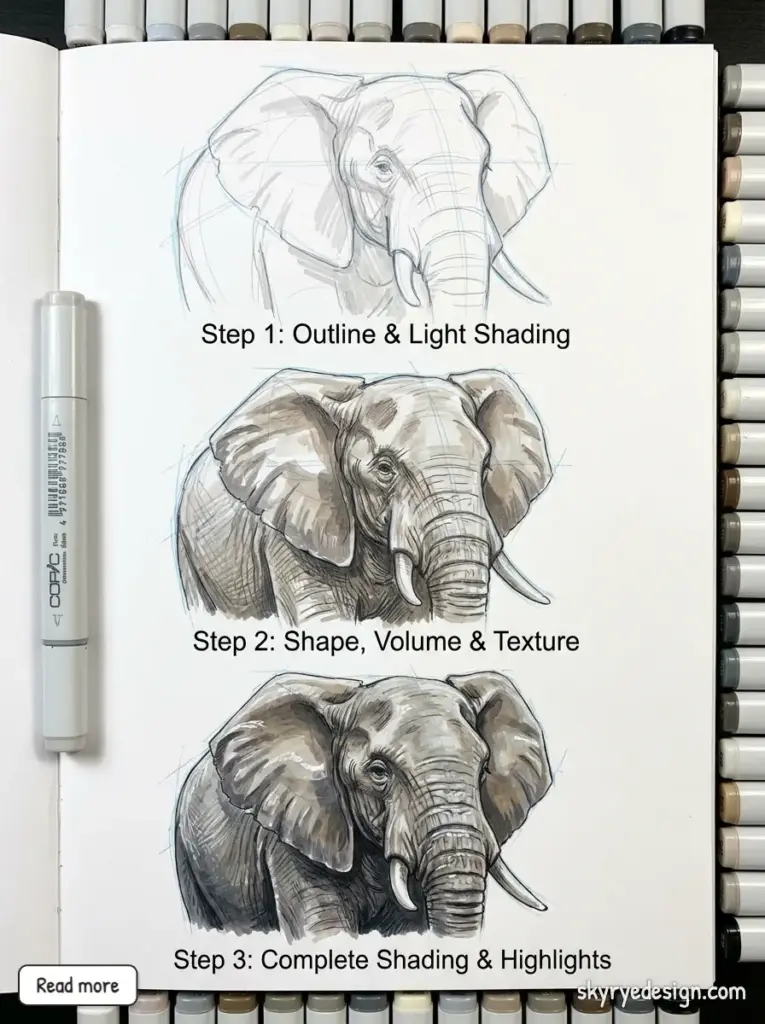

Step 1: Block In the Basic Shapes

Forget details. Right now, you’re building a scaffold.

Draw a large horizontal oval for the body—tilt it slightly so the rear sits a bit higher than the chest. This isn’t a perfect oval; let it be a little lumpy. Real elephants aren’t symmetrical.

Now add a smaller circle for the head, overlapping the front of that body oval. Connect them with two curved lines for the neck. The neck is thicker than you think—elephants aren’t giraffes.

Finally, sketch the trunk as a long, gently curving cylinder. Start wide where it meets the face, then taper it toward the tip.

Proportion check: The body should be roughly five times the length of the head. Measure with your pencil if you need to. Get this wrong and everything else falls apart.

Step 2: Establish the Legs and Posture

Elephant legs aren’t straight columns—that’s the fastest way to make your drawing look stiff.

Draw four thick, pillar-like legs, but add subtle curves at the knee and ankle joints. The front legs angle slightly backward from the shoulder. The back legs angle slightly forward from the hip. This creates stability.

Here’s a trick I learned from animator Aaron Blaise (Brother Bear, The Lion King): look at the negative space between the legs. The shapes between them help you position everything correctly. If those gaps look wrong, your legs are off.

Add flat, rounded pads beneath each foot. Elephants walk on their toes—those pads are essentially thick cushions of fat and tissue absorbing their 12,000-pound footsteps.

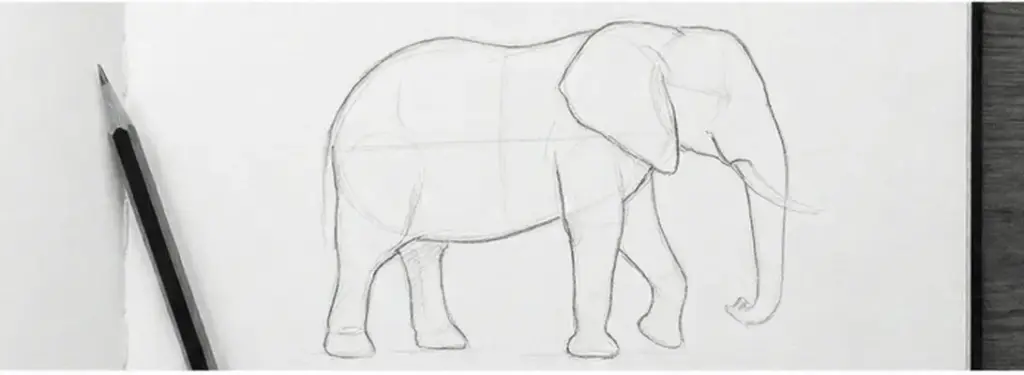

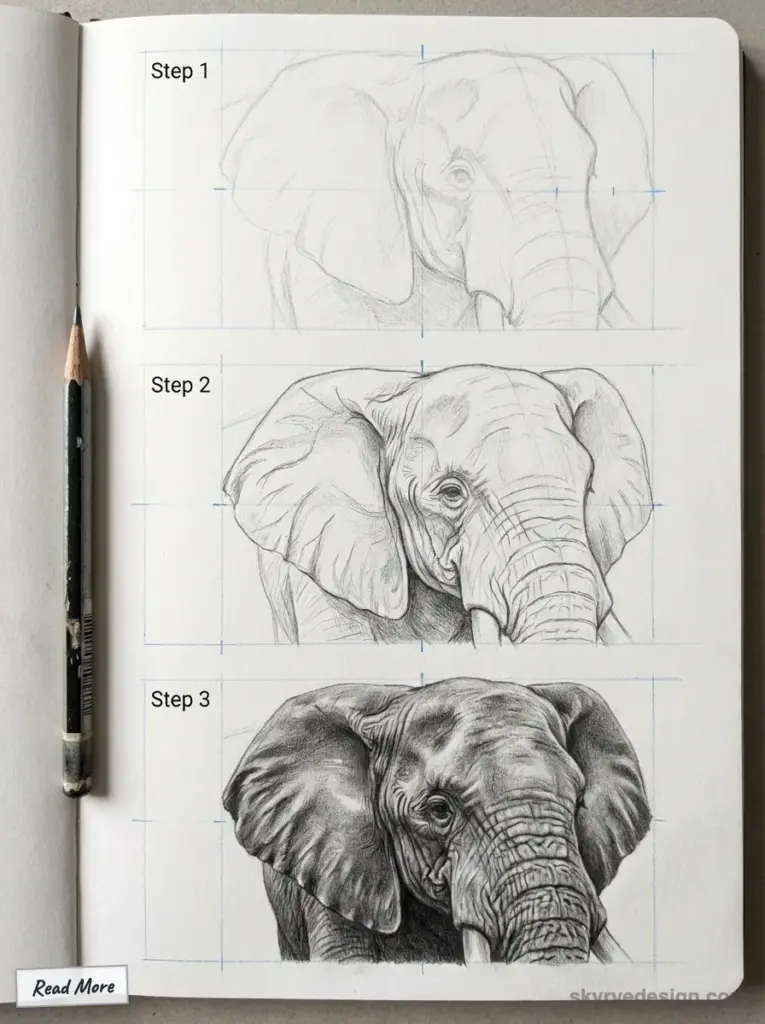

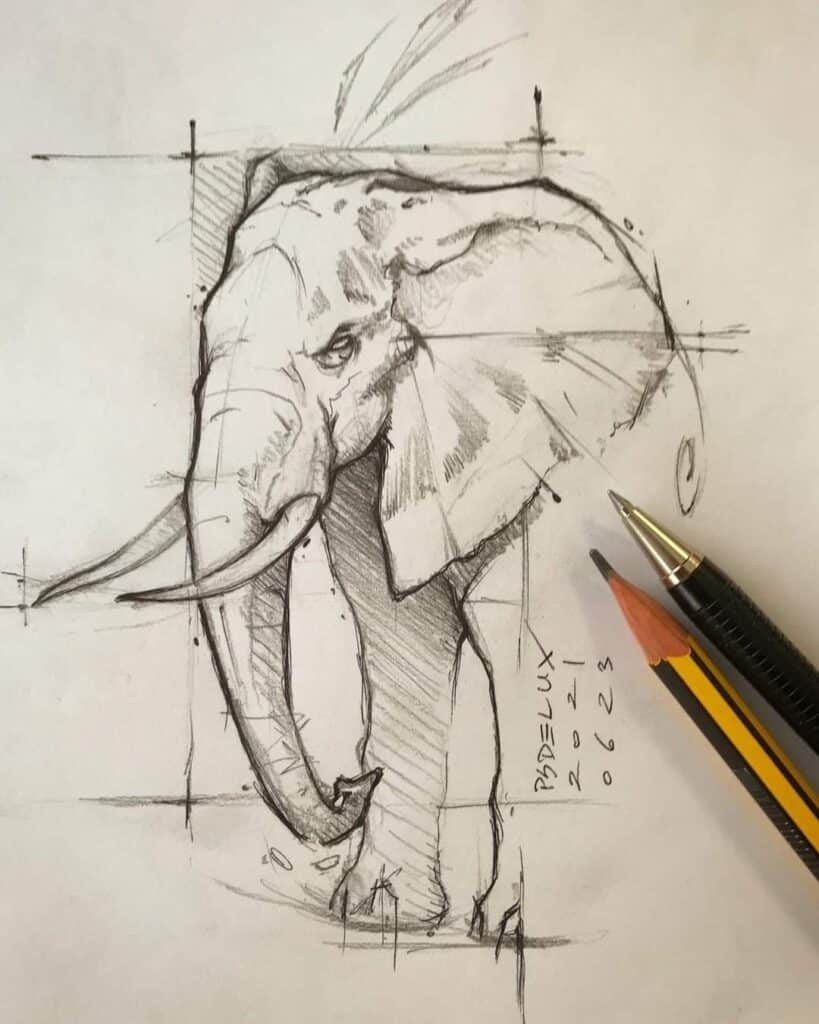

Step 3: Refine the Head, Trunk, and Tusks

Now we’re getting somewhere.

Shape the trunk with more intention. It’s not a uniform tube—it’s wider at the base (almost merging with the upper lip) and tapers gradually. Add a slight S-curve to give it life. Think of a fire hose with water running through it: flexible, heavy, alive.

Position the tusks emerging from below the trunk, curving gently outward and forward. They shouldn’t be too long or too short—roughly the length from the eye to the tip of the trunk works for most adult elephants.

The eye goes low. Lower than you want to put it. Almost level with the top of the trunk’s base. Make it small—about the size of your pencil eraser relative to the head. This is the single most common mistake I see. Beginners place the eye too high and too large, and suddenly the elephant looks like a cartoon.

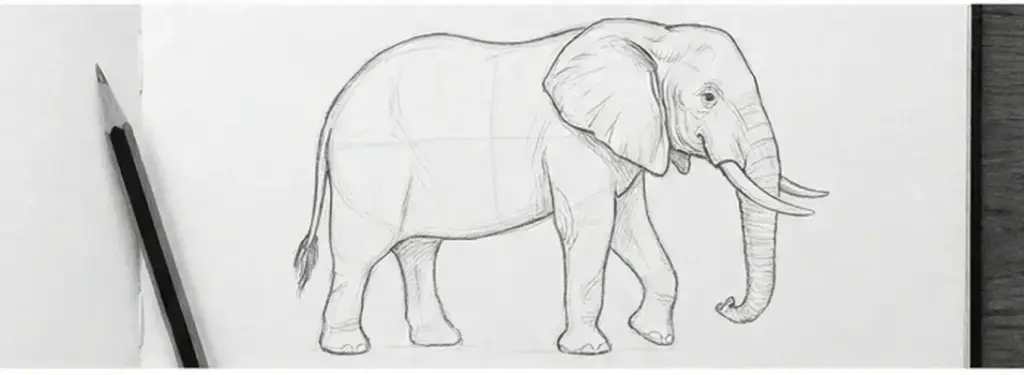

Step 4: Add the Ear and Tail

For an African elephant, the ear is massive. It extends from above the eye all the way down to roughly jaw level—sometimes lower. Picture a sail catching wind. Draw it billowing outward with a wavy, irregular edge. Not smooth. Not perfectly curved. Organic.

Add the tail at the rear: thin, hanging, with a tuft of coarse hair at the tip. It’s an afterthought on most elephants, so don’t overwork it.

Mark the saddle-back dip along the spine—that subtle concave curve that distinguishes African elephants from their Asian cousins.

Step 5: Lay Down Base Shading

Here’s where patience pays off.

Before you touch the wrinkles—before you even think about texture—you need to establish light and shadow. Decide where your light source is. I usually place it above and slightly in front, because that’s how we typically see elephants in photos and films.

Shade the underside of the belly. The area beneath the trunk. The back of the legs. The inside of the ear. Use your 2B pencil and keep the strokes even, then smooth everything with a blending stump.

Leave the top of the back, the forehead, the front of the legs, and the upper trunk lighter.

At this stage, your elephant should look like a smooth gray sculpture. No skin texture. Just form. Volume. Mass.

This is the step most people skip. They jump straight to wrinkles and end up with a flat drawing covered in lines. Don’t do that. Build the foundation first.

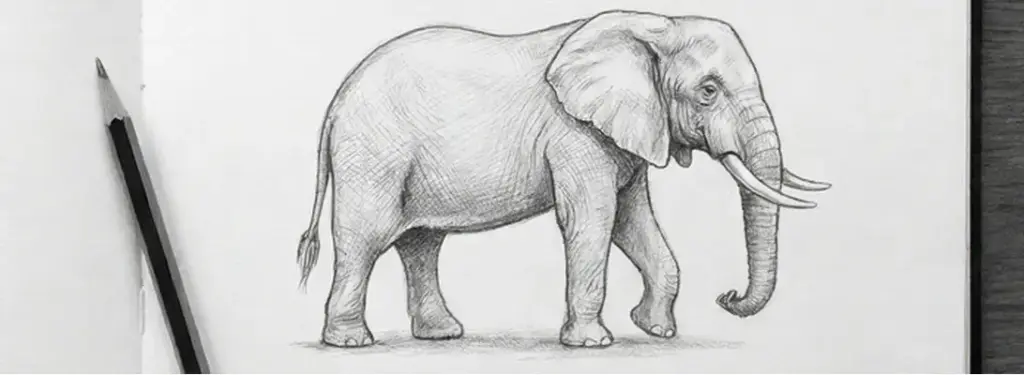

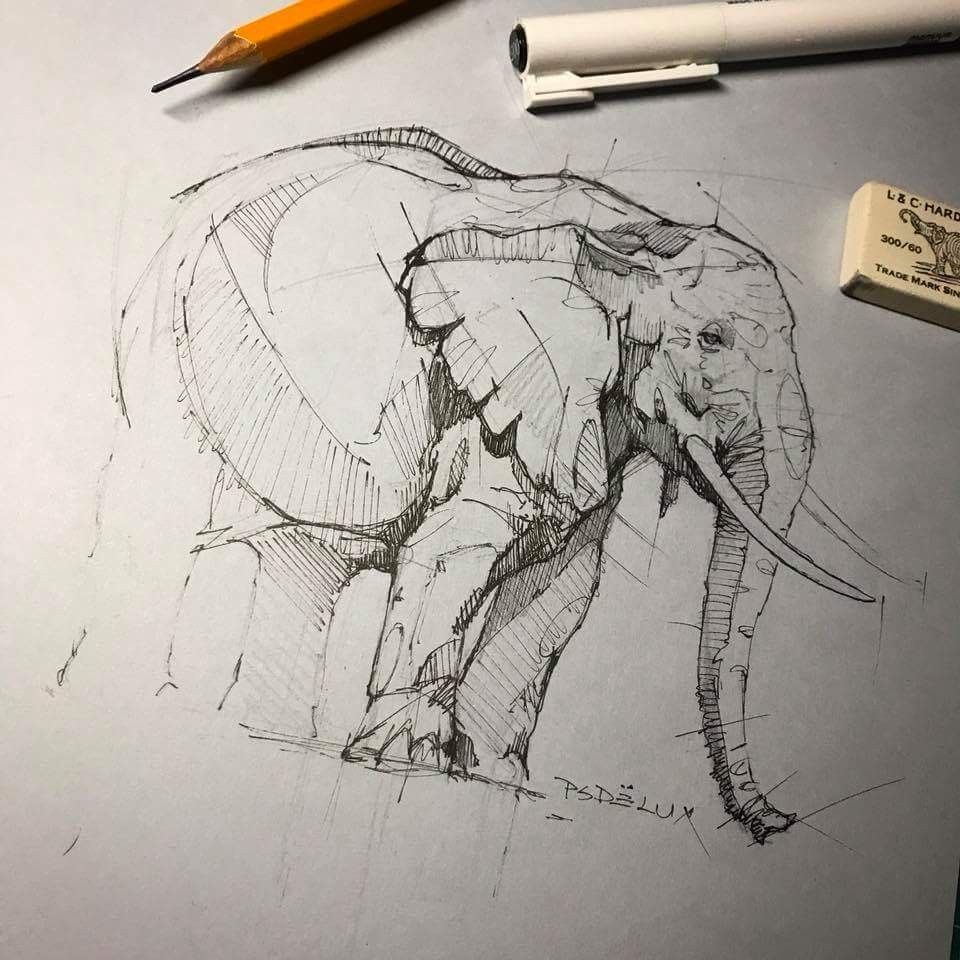

The Hard Part: Drawing Elephant Skin Texture

This is where most elephant drawings fall apart—or come alive.

You’ve got your smooth, shaded elephant from Step 5. It looks decent. Solid, even. Now you’re tempted to grab your darkest pencil and start adding wrinkles everywhere.

Don’t.

Elephant skin isn’t uniform. The texture on a trunk looks nothing like the texture on a hip. The ears are different from the legs. If you apply the same technique across the entire body, you’ll end up with a muddy, overworked mess. I’ve ruined more than a few drawings learning this the hard way.

Technique 1: Deep Creases (Hips and Rear Legs)

The skin around an elephant’s hindquarters has the deepest, most dramatic wrinkles—thick folds that catch serious shadow.

Here’s the approach:

- Lightly sketch the crease shapes first. They’re not straight lines; they curve and branch like dry riverbeds.

- Go over them with your 4B or 6B pencil, thickening the lines unevenly. Add bulges. Wobbles. Nothing perfectly smooth.

- Shade beneath each crease, leaving a thin strip of highlight along the top edge.

That highlight is everything. It’s what makes the skin look three-dimensional instead of like someone drew stripes on a gray balloon.

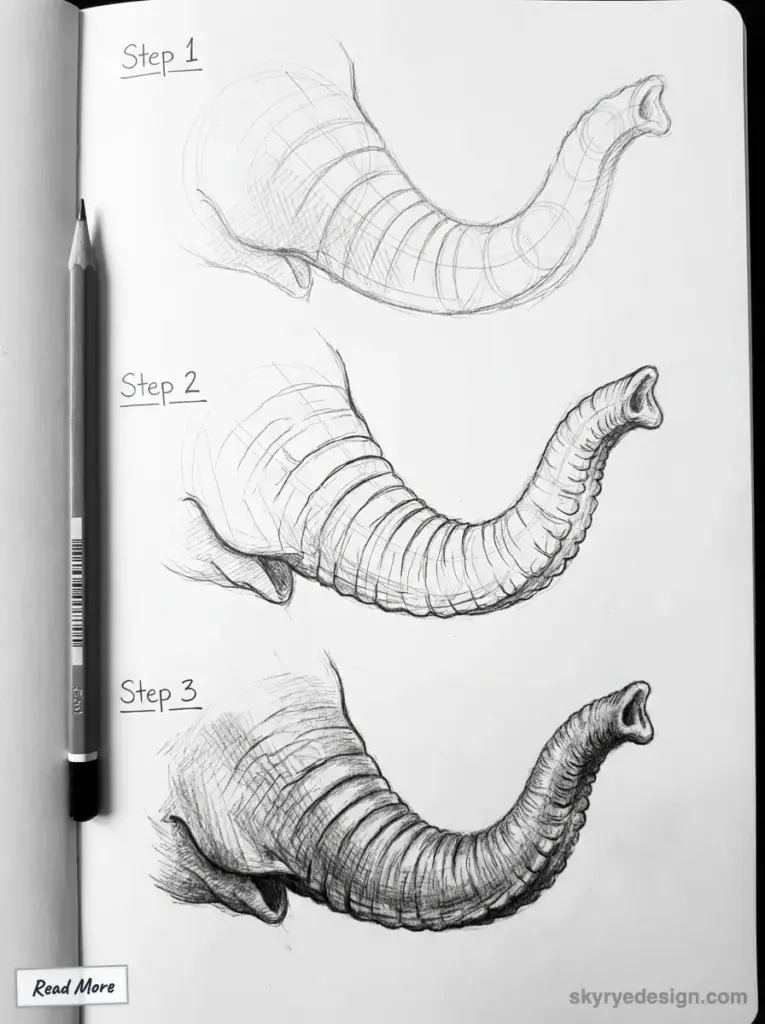

Technique 2: Trunk Rings

The trunk has its own logic. Those horizontal rings you see in photos? They’re not complete circles—they’re broken, interrupted lines that wrap partway around.

Draw them as arcs, not full rings. Vary the spacing. Some closer together, some further apart. Then add short vertical notches between the rings to break up the pattern. Real trunks have this irregular, crosshatched quality.

Keep the underside of the trunk darker. The tip especially—it’s almost always in shadow.

Common mistake: Perfect, evenly-spaced rings. Dead giveaway of a rushed drawing. Nature doesn’t do uniform.

Technique 3: Fine Body Texture (Crosshatching)

For the main body, shoulders, and front legs, you’re not drawing individual wrinkles. You’re suggesting texture.

Use your 2B pencil to create a fine mesh of short, intersecting lines—crosshatching, essentially. Vary your pressure. Some areas darker, some lighter. Let the lines follow the form of the body, curving slightly over the shoulder and down the leg.

The key: restraint. You’re not drawing every wrinkle. You’re giving the viewer’s eye enough information to fill in the rest. Jess Ridley, a UK-based wildlife artist whose elephant portraits are stunning, describes her process as “map, scribble, blend, erase—times a thousand.” That’s the rhythm.

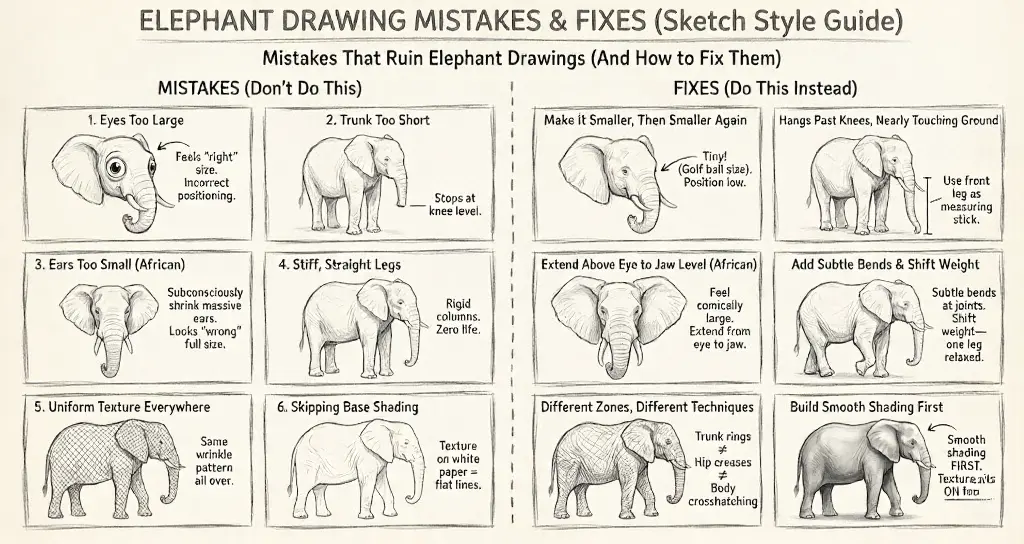

6 Mistakes That Ruin Elephant Drawings (And How to Fix Them)

I’ve made every single one of these. Some of them multiple times. Here’s what to watch for—and how to fix it before you’ve gone too far.

1. Eyes Too Large

The problem: You draw the eye the size it “feels” like it should be. But elephant eyes are tiny—about the size of a golf ball on a 12,000-pound animal.

The fix: Make the eye smaller than feels right. Then make it smaller again. Position it low, almost level with the top of the trunk.

2. Trunk Too Short

The problem: The trunk stops somewhere around knee level.

The fix: A relaxed trunk hangs past the knees, nearly touching the ground. Use the front leg as your measuring stick.

3. Ears Too Small (African Elephants)

The problem: You subconsciously shrink those massive African ears because they look “wrong” at full size.

The fix: Let them extend from above the eye down to jaw level. They should feel almost comically large. They’re not.

4. Stiff, Straight Legs

The problem: Four rigid columns. Zero life.

The fix: Add subtle bends at the knees and ankles. Shift the weight slightly—one leg relaxed, others bearing load. Watch how elephants stand in videos; they’re always adjusting.

5. Uniform Texture Everywhere

The problem: Same wrinkle pattern from trunk to tail.

The fix: Different zones, different techniques. Trunk rings ≠ hip creases ≠ body crosshatching.

6. Skipping Base Shading

The problem: Jumping straight to texture on white paper. The wrinkles look like lines drawn on a flat surface—because they are.

The fix: Always build smooth shading first. Texture sits on top of form, not instead of it. This single fix transforms more drawings than any other.

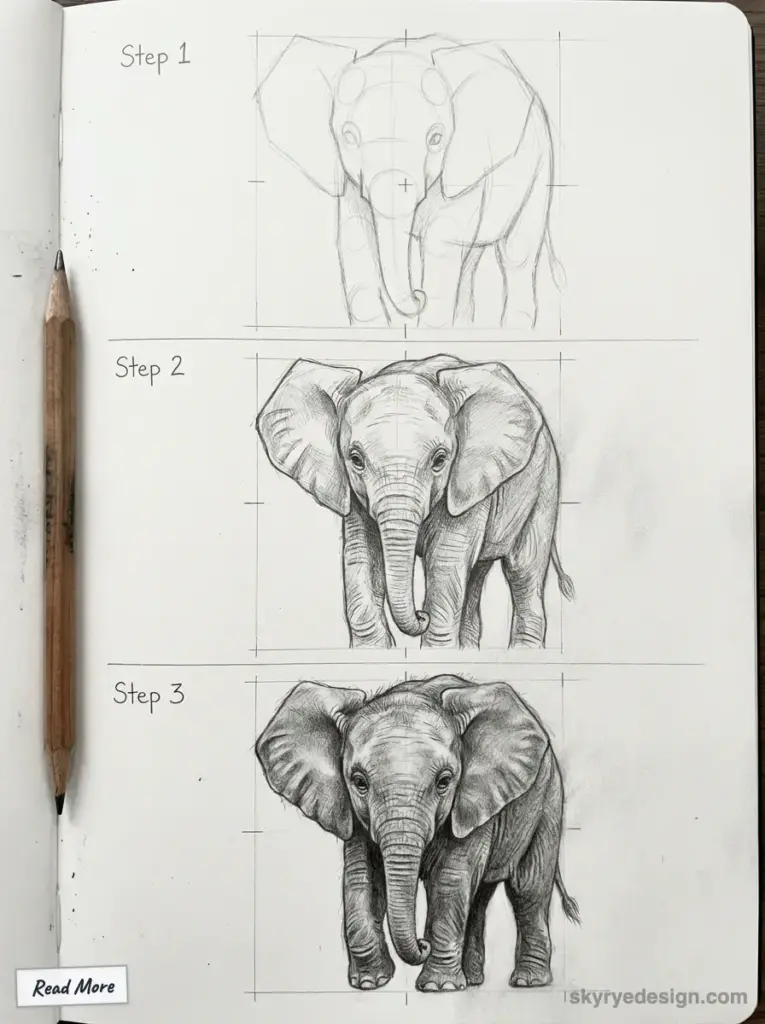

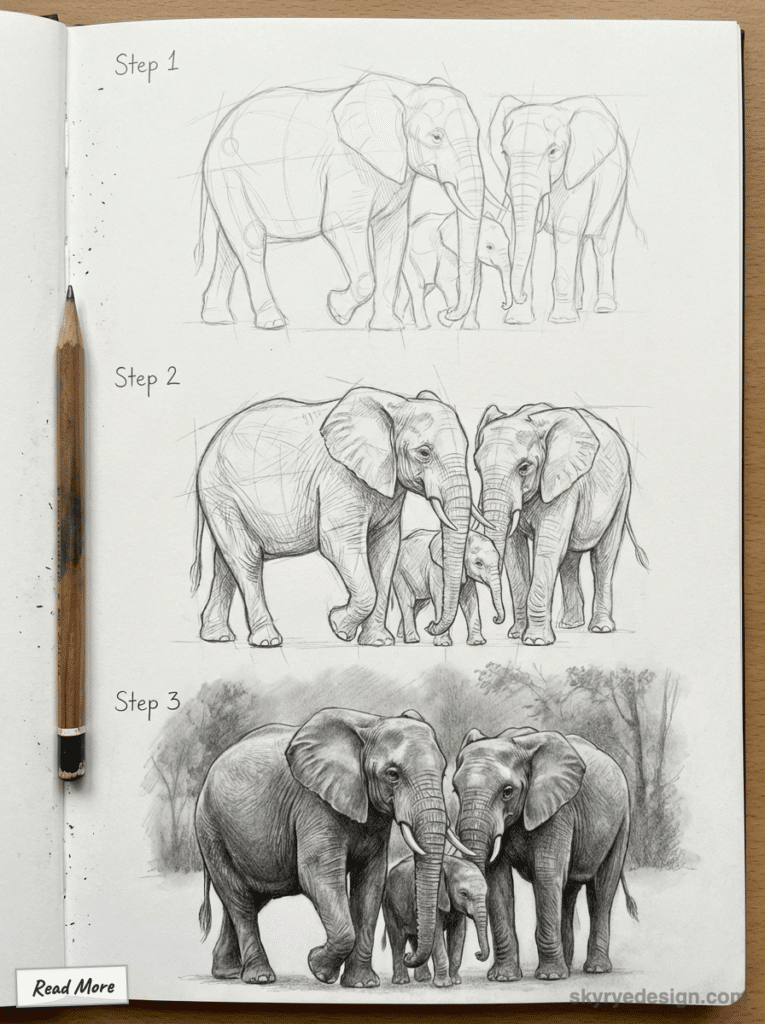

Taking It Further: Poses, Babies, and Herds

You’ve drawn a standing elephant. Now what?

Movement and Emotion

Static poses are a starting point, not a destination. Once you’re comfortable with proportions, start pushing into action.

A walking elephant leans forward slightly, one front leg extended. A trumpeting elephant raises its trunk high, ears flared wide—it’s a threat display, full of tension. A drinking elephant curls its trunk toward its mouth, head dipped low.

The ears alone tell a story. Relaxed and flat against the body? Calm. Spread wide and facing forward? Alert or aggressive. I spent an afternoon watching footage from Sheldrick Wildlife Trust’s orphan rescue center in Kenya—their YouTube channel is gold for studying how baby elephants move and interact. Free reference material, straight from Nairobi.

Baby Elephants and Family Groups

Calves are all head. Their proportions are exaggerated—bigger skull relative to body, ears that seem slightly too large, legs a little wobbly. They’re almost always drawn near their mothers, tucked underneath or pressing against a leg.

Herds create compositional opportunities: overlapping forms, varied sizes, implied relationships. A matriarch leading. A calf trailing. Three generations in one frame.

One challenge to try: Draw two elephants interacting. Trunks touching, bodies overlapping. It forces you to think about depth and connection—not just anatomy.

FAQ: Your Elephant Drawing Questions, Answered

Is drawing an elephant hard for beginners?

Harder than a cat, easier than a horse. Elephants have forgiving proportions—big, blocky shapes without complex muscle definition. The challenge is texture and getting those small details right (eye size, ear shape). Most beginners produce a decent elephant within three or four attempts. Start with a side profile; it’s the most straightforward angle.

What’s the easiest part of an elephant to draw?

The tusks and tail. Two curved lines for the tusks, a thin wiggly line with a tuft for the tail—done. The body is moderately easy once you understand the basic oval structure. The trunk and skin texture are where people struggle most, which is why I dedicated an entire section to each.

Should I use a reference photo or draw from imagination?

Reference. Always. Even Disney animators use reference—Glen Keane famously studied real bears for months before animating Beast. Find photos with strong directional lighting that shows form and shadow. Flat, evenly-lit images make everything harder. I keep a folder of 30+ elephant references sorted by pose and species.

How long does a realistic elephant drawing take?

A quick sketch: 15-20 minutes. A fully rendered drawing with texture and shading: 2-4 hours, depending on size and detail level. The timelapse in this tutorial represents about three hours of actual drawing time. Don’t rush the base shading—it’s the foundation everything else sits on.

Can I draw an elephant with pen instead of pencil?

Yes, but sketch in pencil first. Ink is permanent—one wrong line and you’re committed. I like Micron 01 and 05 pens for final linework, or a simple Bic ballpoint for looser, sketchier texture. Ballpoints are surprisingly good for building up tone through layered hatching.

Why does my elephant look flat?

You probably skipped base shading. Wrinkles drawn on white paper look like lines, not form. Build smooth gradients first—dark underneath, light on top—then add texture over that foundation. Also check your value range: beginners often stay in the mid-grays. Push your darks darker.

African or Asian—which is easier to draw?

Asian, slightly. The smaller ears are less intimidating, and the smoother skin means less texture work. But African elephants are more commonly referenced in Western media, so you’ll find more photo references. Pick whichever species you connect with—you’ll draw it better if you actually care about it.

Now Go Draw One

Here’s the thing about drawing elephants: you won’t get it right the first time. Or probably the second.

But that’s the point. Each attempt teaches you something—about proportion, about texture, about how these animals actually look when you slow down and observe them. Craig the Tusker is gone. So are thousands of elephants before him. Drawing them is one small way to pay attention. To remember.

So grab your pencil. Pull up a reference photo—African or Asian, your choice. Block in those shapes. Get the eyes too big on your first try (you will), then fix them.

And when you finish something you’re proud of, tag me. I’m @skyryedesign everywhere. Use #SkyRyeDesign.

I want to see your elephants.

- 520shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest520

- Twitter0

- Reddit0