A practical anatomy guide for artists, illustrators, and character designers

- Introduction: This Is Not a Biology Lesson

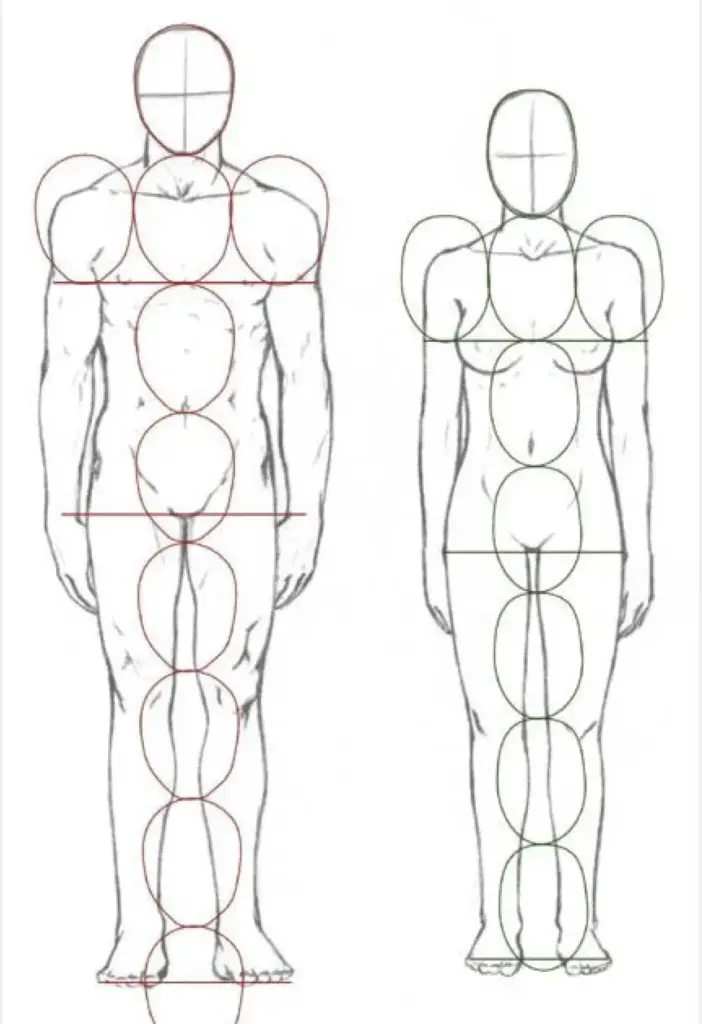

- Body Proportions in Head Units (The Artist’s Measuring System)

- The Skeleton: The Hidden Structure Behind the Drawing

- Shoulders vs Hips: The Core Proportional Contrast

- Ribcage and Pelvis: How the Torso Is Built

- Muscle Distribution (What Actually Changes Visually)

- Fat Distribution → Flow of Lines (Very Important)

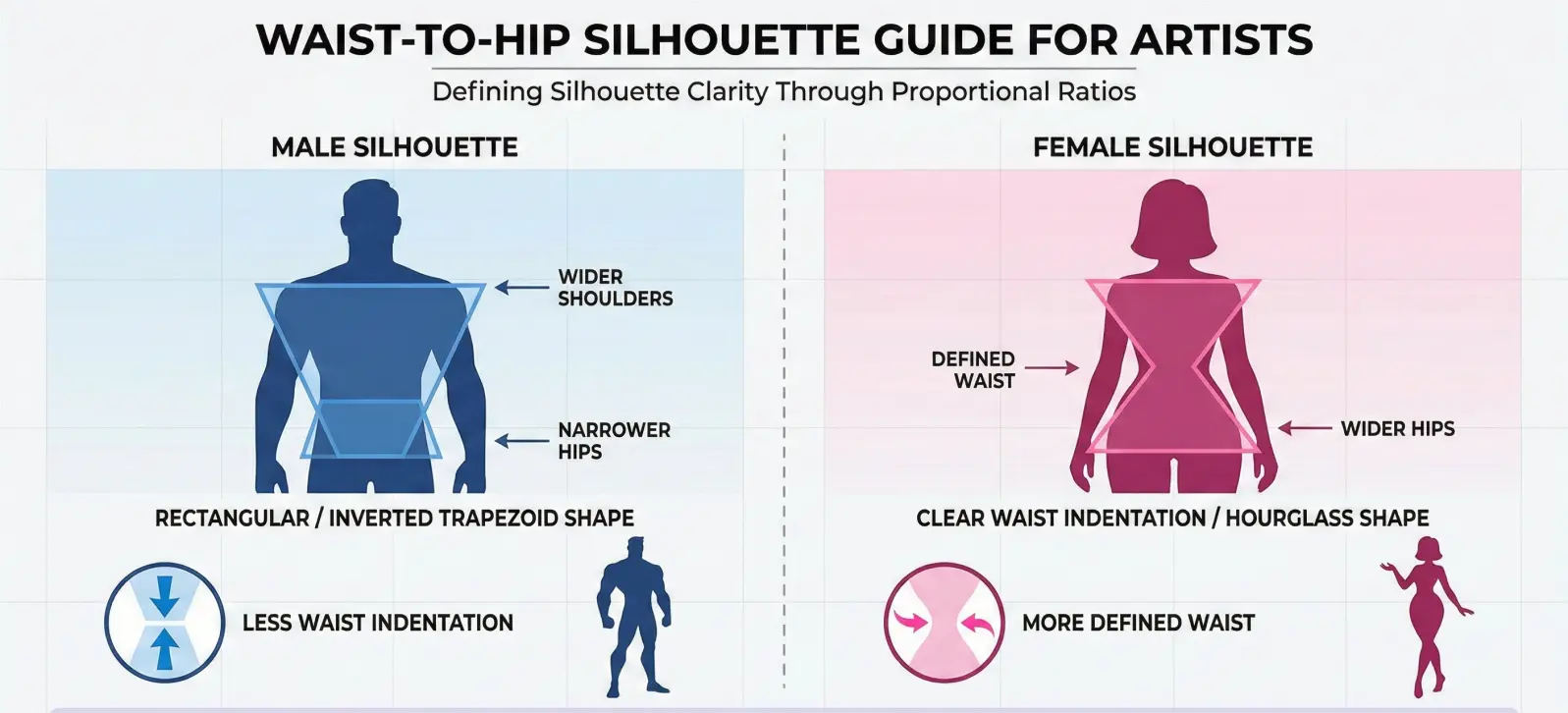

- Waist-to-Hip Relationship (Silhouette Design)

- Legs vs Torso Length

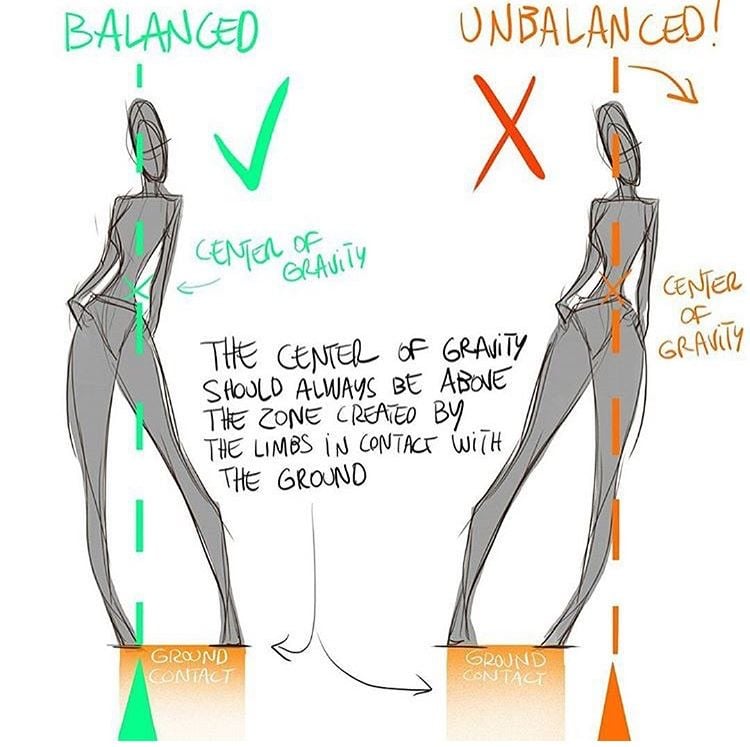

- Center of Gravity (Critical for Gesture Drawing)

- Joint Mobility and Pose Design

- Common Drawing Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

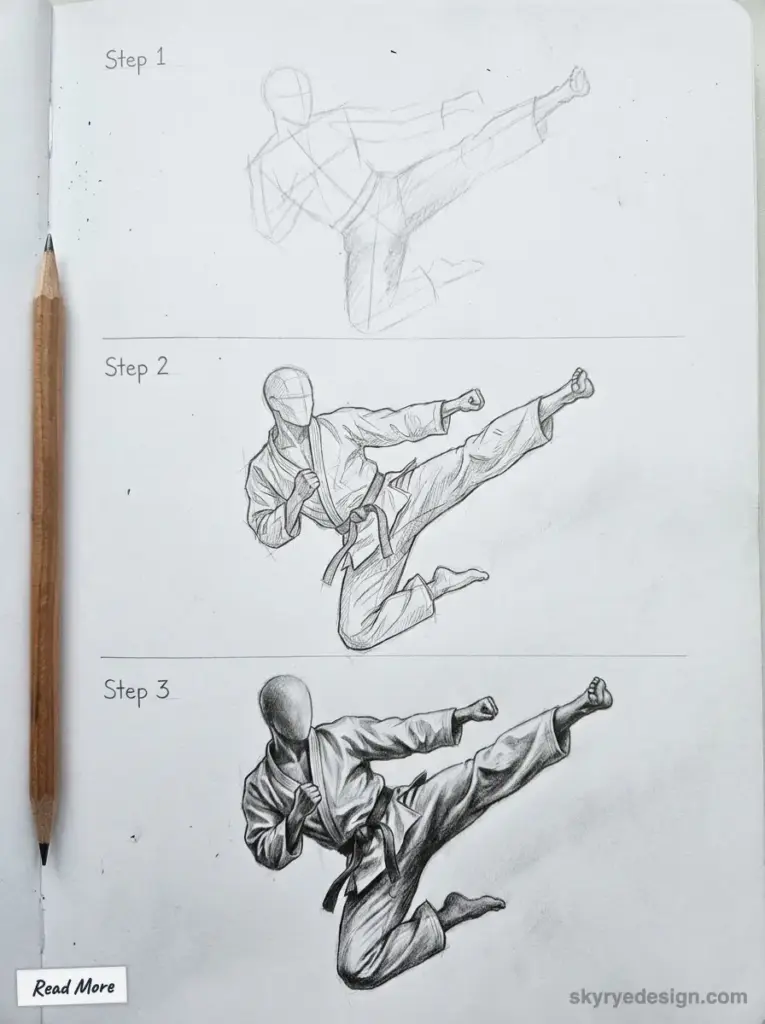

- Visual Reference Suggestions (For This Article)

- Final Thoughts for Artists

Introduction: This Is Not a Biology Lesson

If you’re an artist, you don’t need medical terminology to draw convincing human figures.

What you do need is a clear understanding of proportions, balance, and visual rhythm.

Male and female bodies are built from the same basic parts — the difference lies in how those parts are proportioned, connected, and simplified into shapes. These proportional differences affect:

- Gesture and line of action

- Silhouette readability

- Weight distribution and balance

- Whether a figure feels stiff, soft, powerful, or elegant

This guide explains male vs female body proportions in a way artists actually use — through head units, shape language, and drawing logic. Every section includes a “For Artists” block with direct, practical advice you can apply immediately.

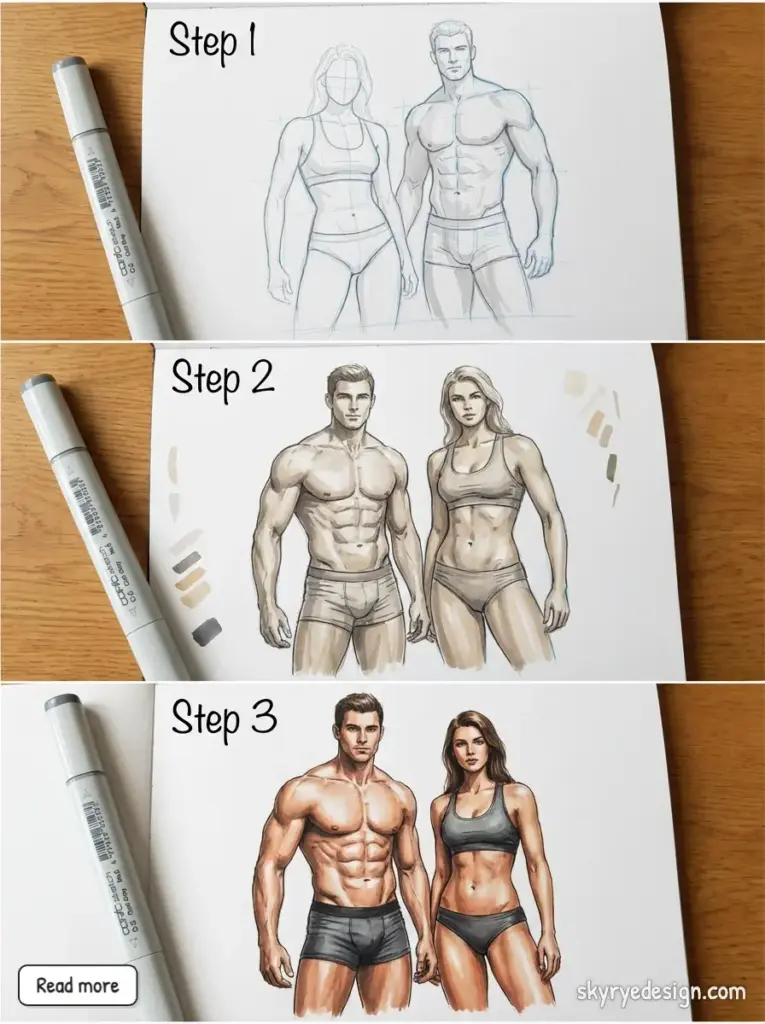

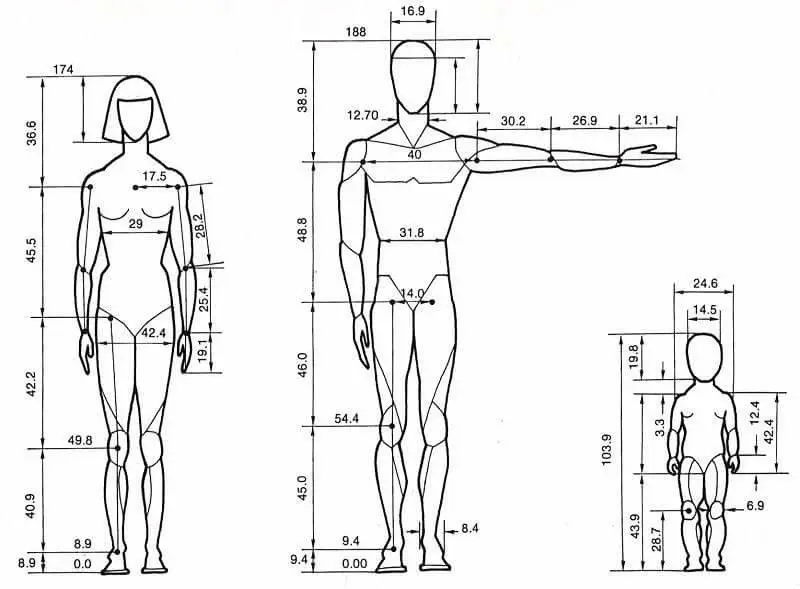

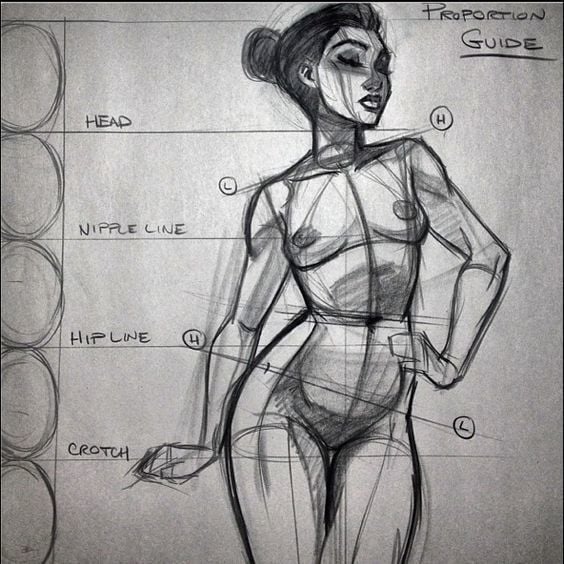

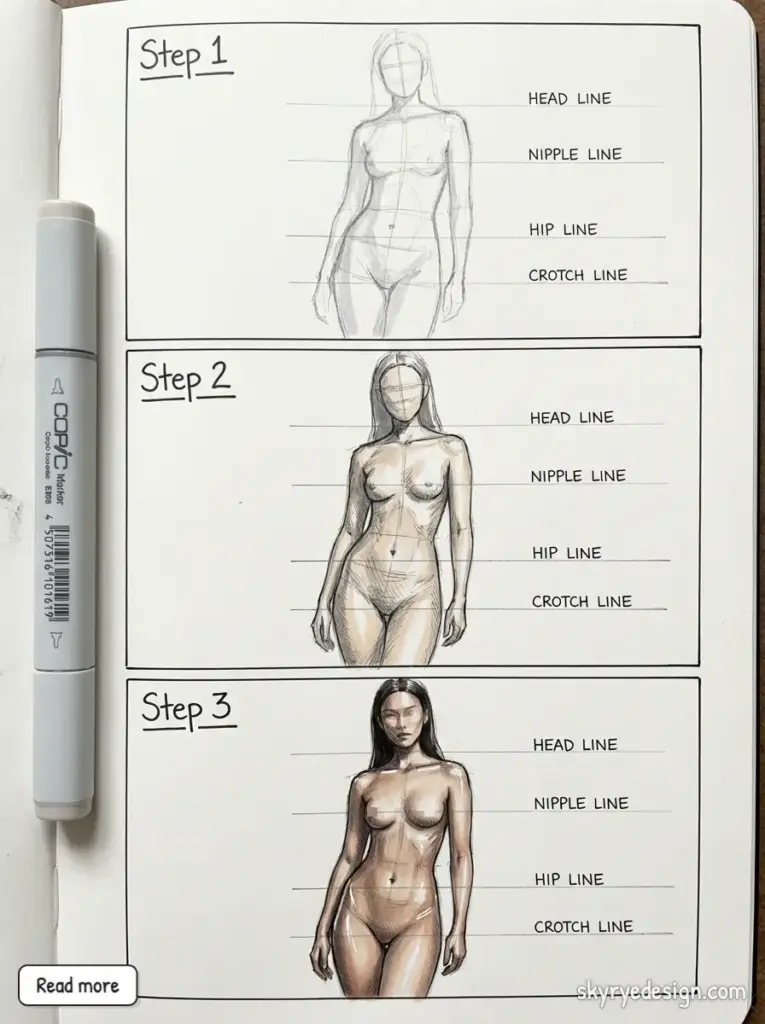

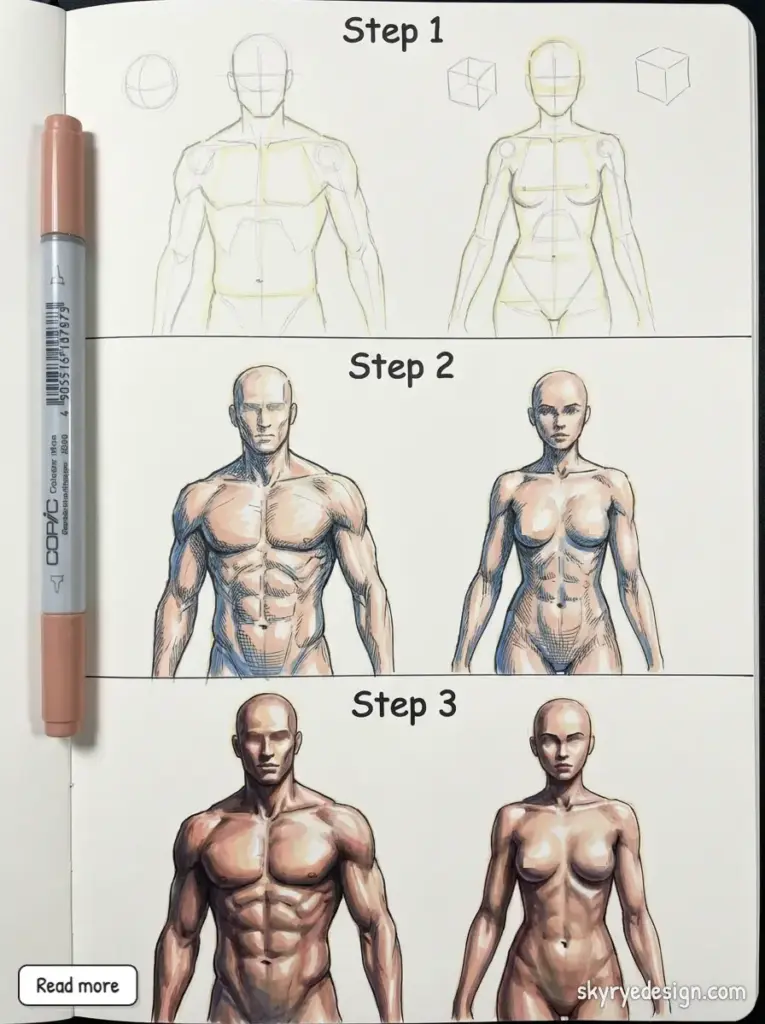

Body Proportions in Head Units (The Artist’s Measuring System)

Before we talk about shoulders, hips, or muscles, we need a shared measuring tool.

In academic figure drawing, proportions are measured in head units, not centimeters.

Standard Academic Proportions

- Male figure: ~ 8 heads tall

- Female figure: ~ 7.5 heads tall

This half-head difference might seem small, but visually it changes the entire impression of the figure.

Shoulder width is also measured in heads:

- Male shoulders: ~ 2.0–2.3 head widths

- Female shoulders: ~ 1.5–1.8 head widths

For Artists

- If your male figure looks soft or adolescent, check if the body is closer to 7–7.5 heads.

- If your female figure looks bulky or masculine, the shoulders are often too wide relative to the head.

- Always block in the head first, then build the body outward using head units as your ruler.

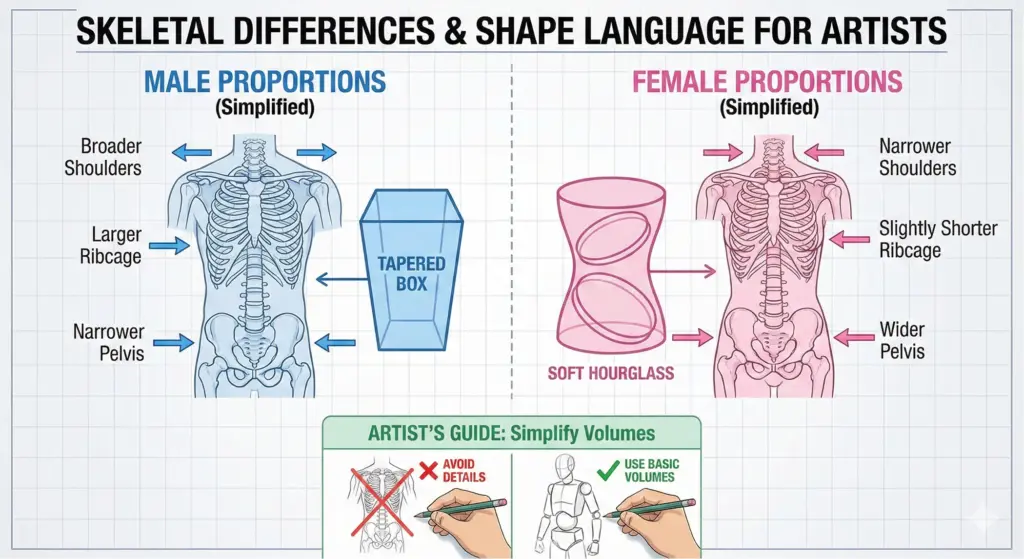

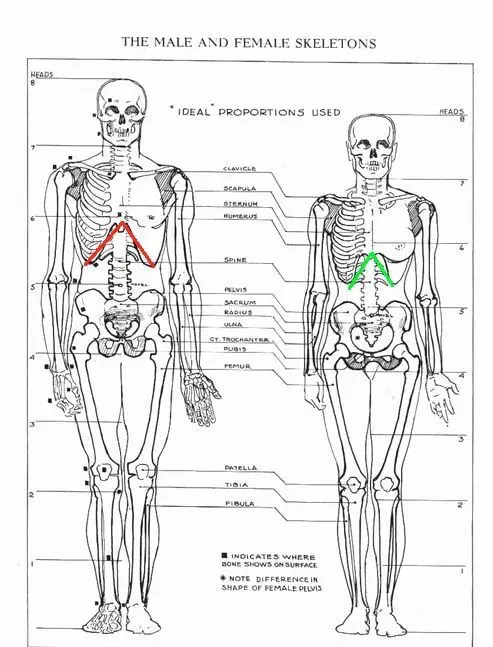

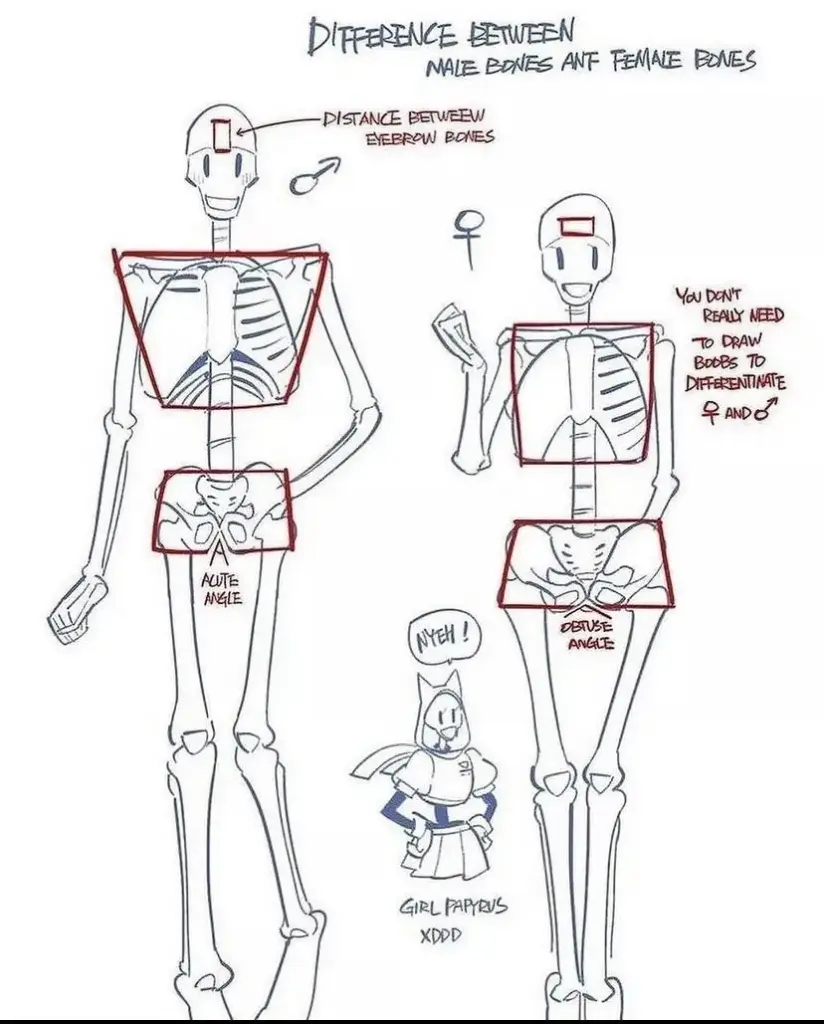

The Skeleton: The Hidden Structure Behind the Drawing

You don’t need to draw skeletons every day — but you do need to understand what they imply.

The skeleton determines:

- Width vs height

- Where curves appear

- How weight is supported

Key Skeletal Differences (Simplified)

- Male skeleton

- Broader shoulders

- Narrower pelvis

- Larger ribcage

- Female skeleton

- Narrower shoulders

- Wider pelvis

- Slightly shorter ribcage

These differences affect the overall shape language of the figure.

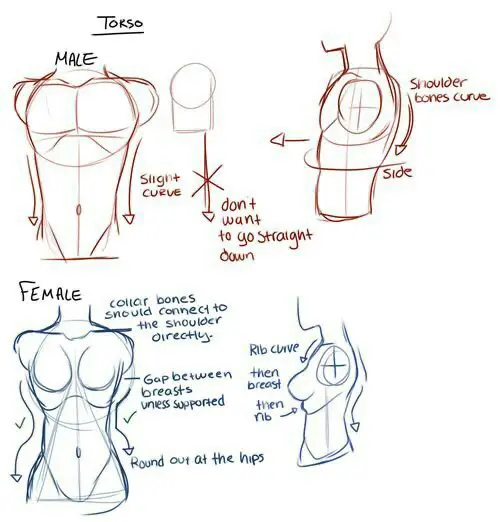

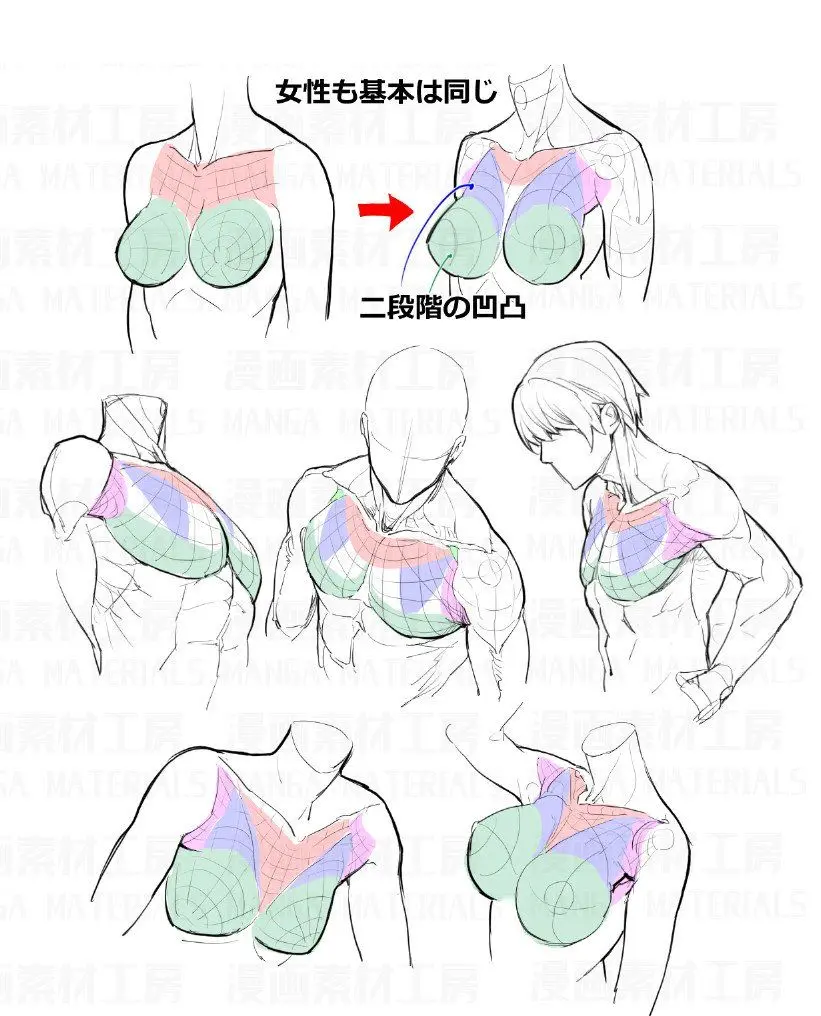

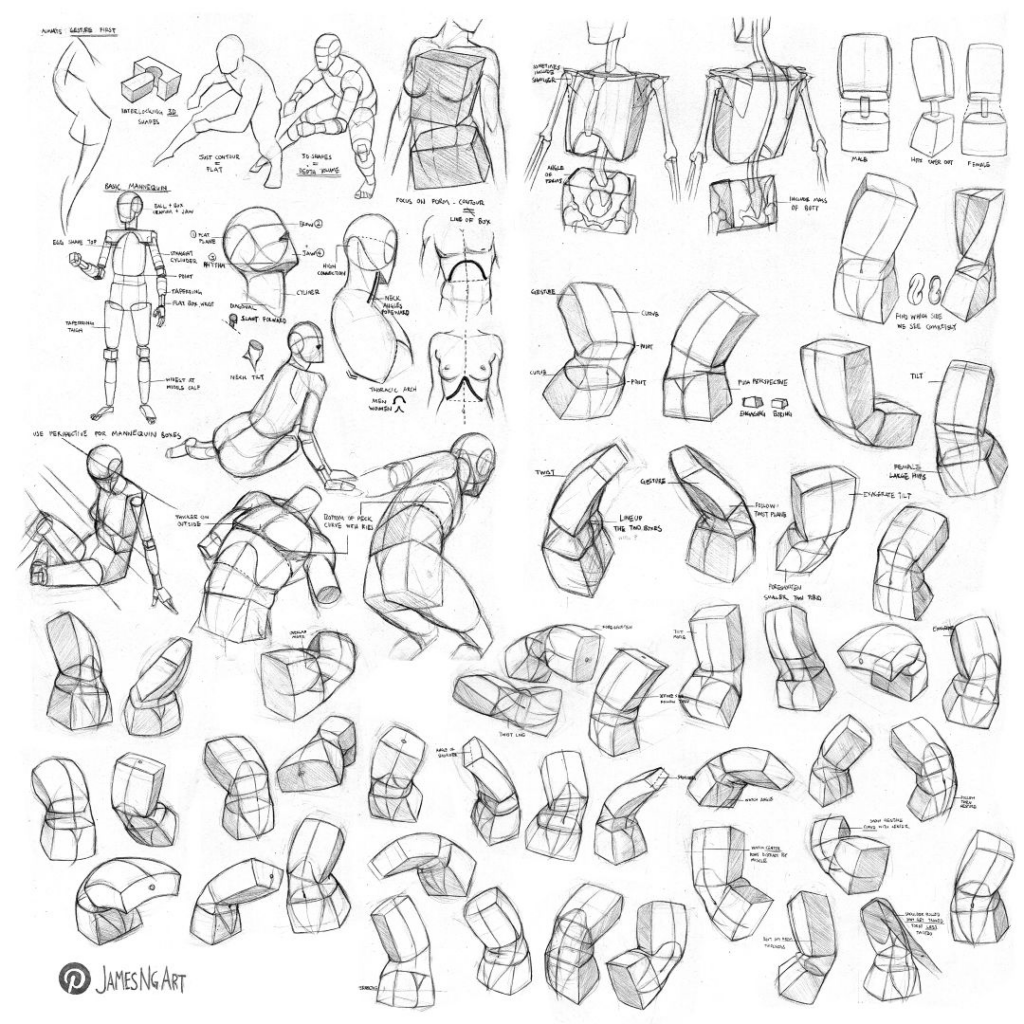

For Artists

- Think of the male torso as a tapered box (wide top → narrow bottom).

- Think of the female torso as a soft hourglass or two offset ovals.

- Don’t copy details — simplify the skeleton into basic volumes before adding anatomy.

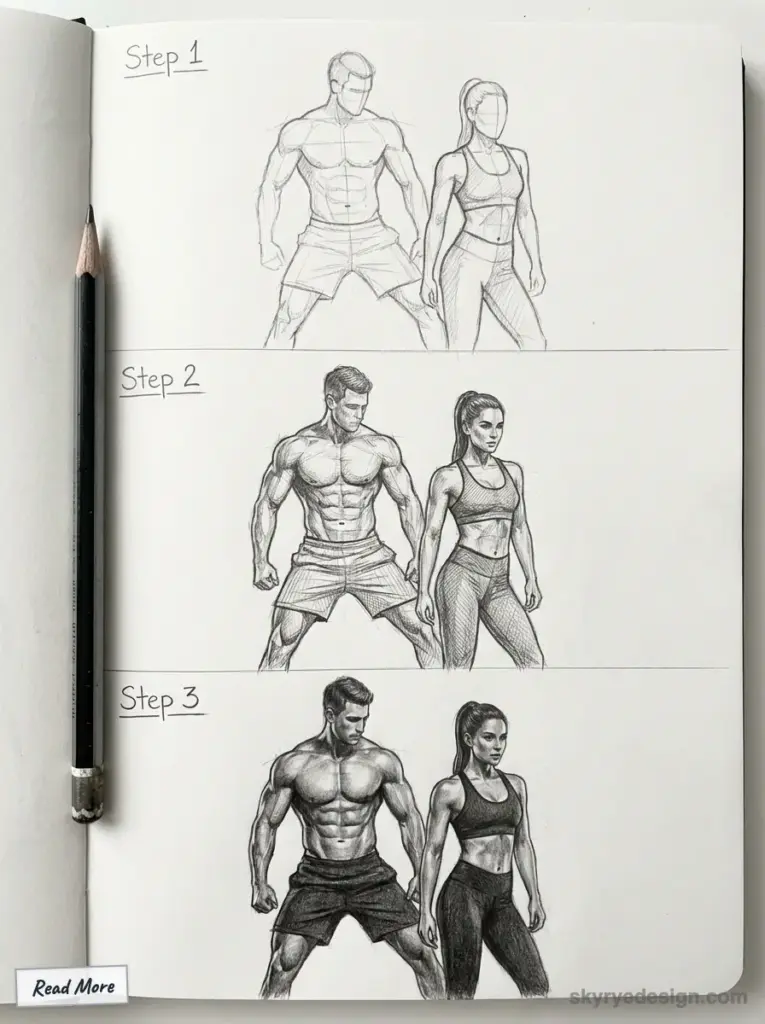

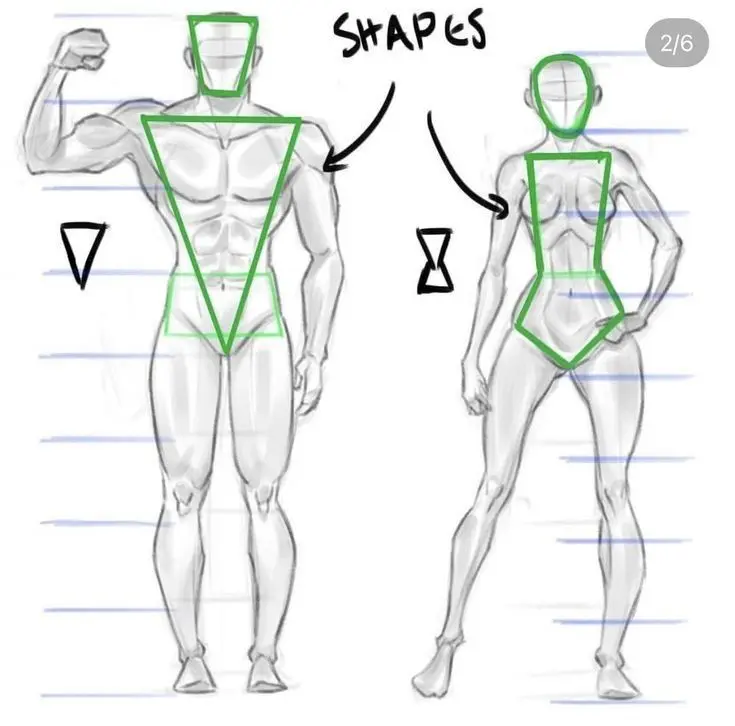

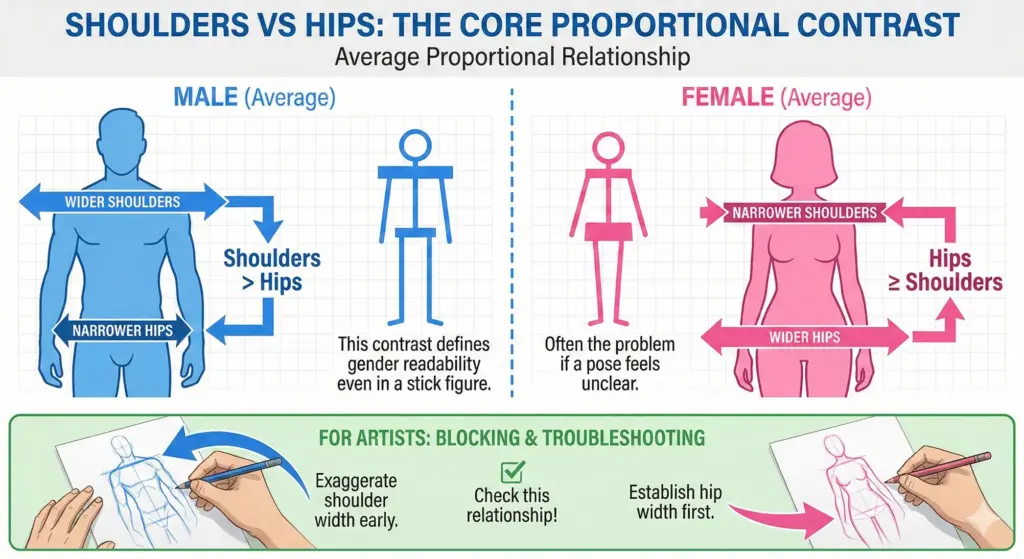

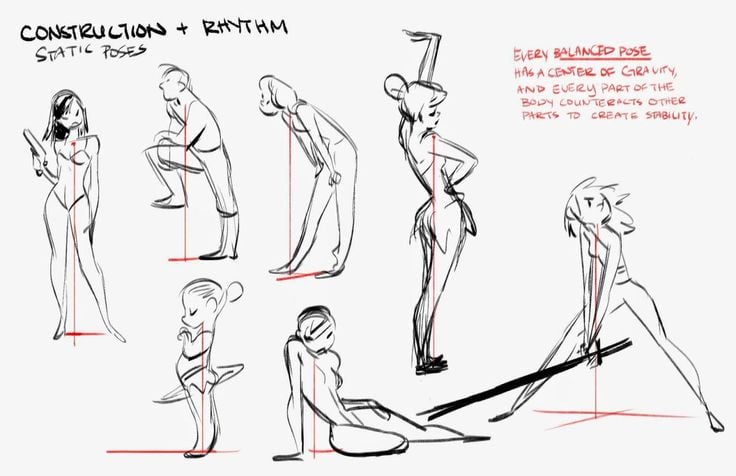

Shoulders vs Hips: The Core Proportional Contrast

This is one of the most important visual differences.

Average Proportional Relationship

- Male: Shoulders wider than hips

- Female: Hips wider than shoulders (or roughly equal)

This contrast alone can define gender readability even in a stick figure.

For Artists

- When blocking a male figure, exaggerate the shoulder width early.

- When blocking a female figure, establish the hip width first.

- If a pose feels unclear, check this relationship — it’s often the problem.

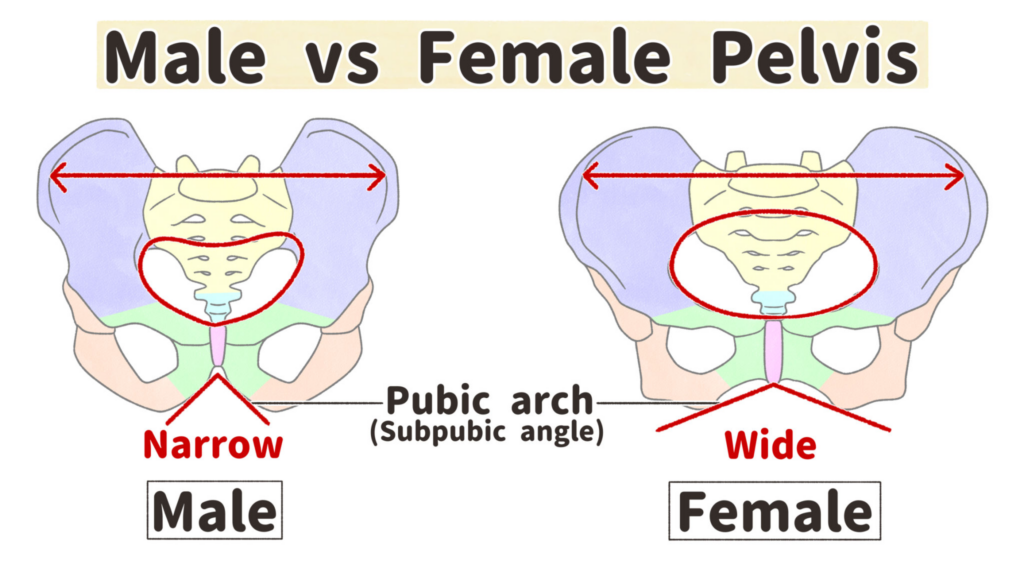

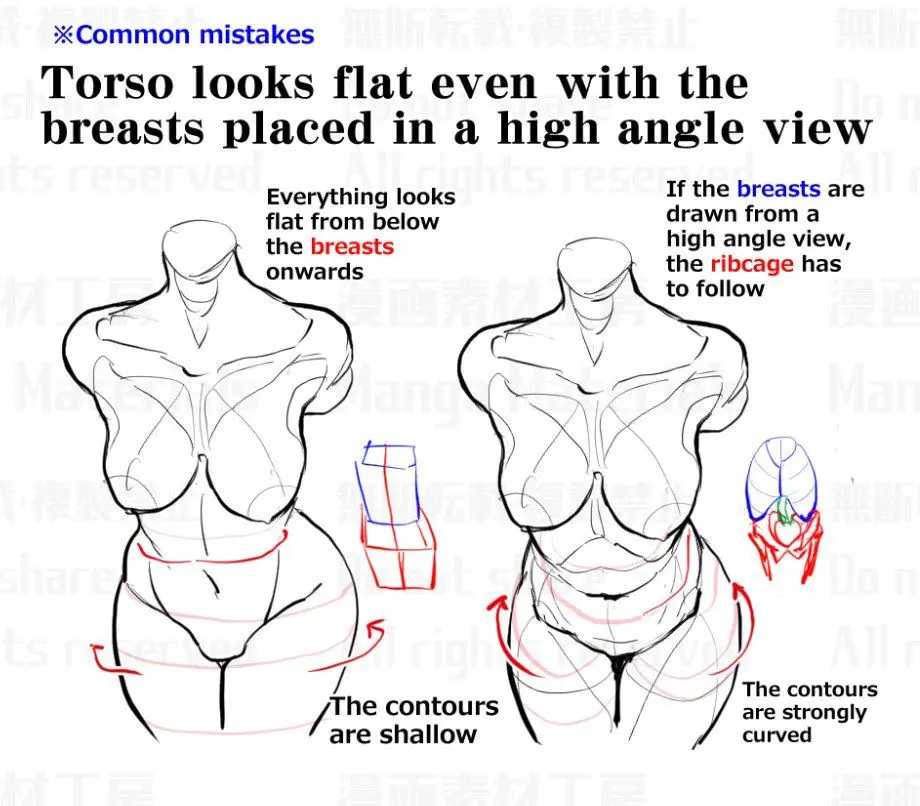

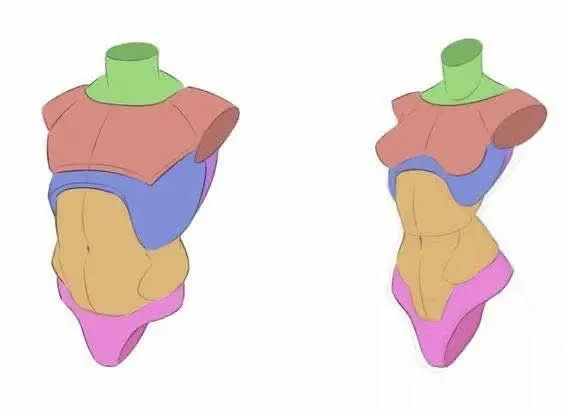

Ribcage and Pelvis: How the Torso Is Built

The torso isn’t one shape — it’s two masses:

- Ribcage

- Pelvis

Structural Differences

- Male

- Larger ribcage

- Ribcage and pelvis align more vertically

- Female

- Smaller ribcage

- Ribcage often tilts relative to the pelvis

This tilt creates natural curves and rhythm.

For Artists

- Draw the ribcage and pelvis as separate forms.

- In female figures, allow more twist and offset between them.

- In male figures, keep them more stacked and aligned for solidity.

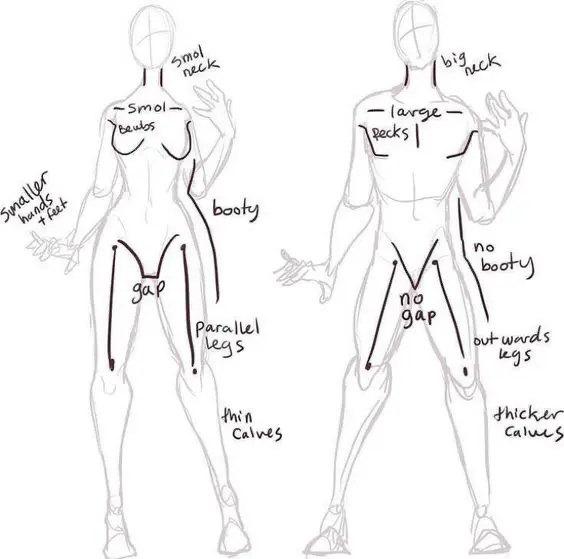

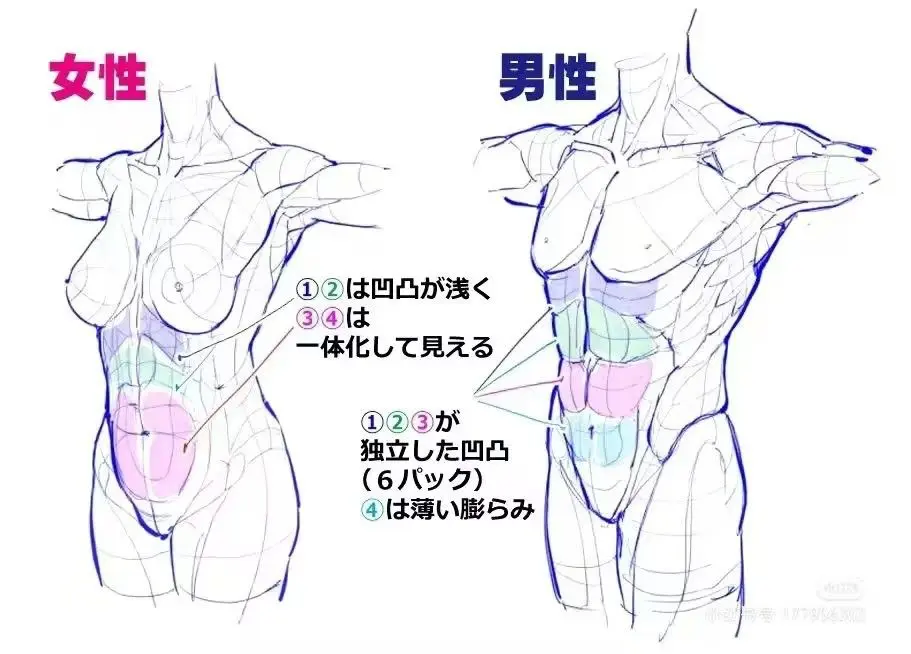

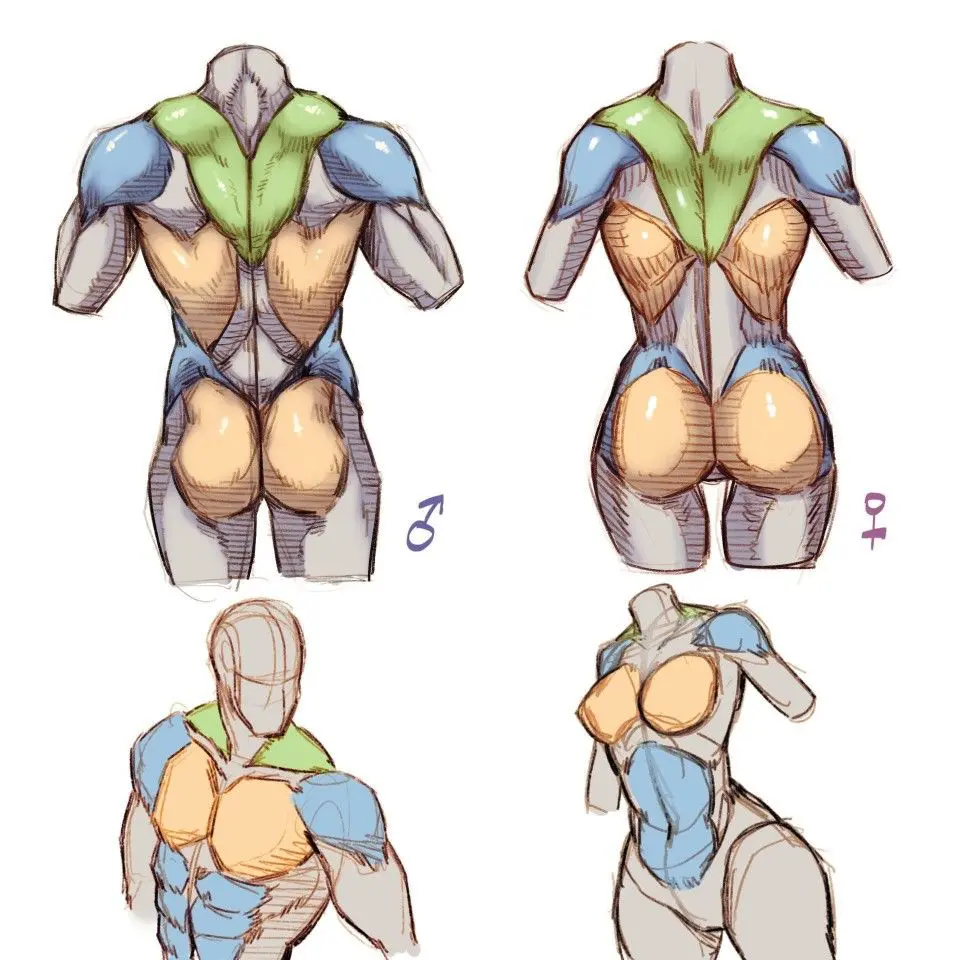

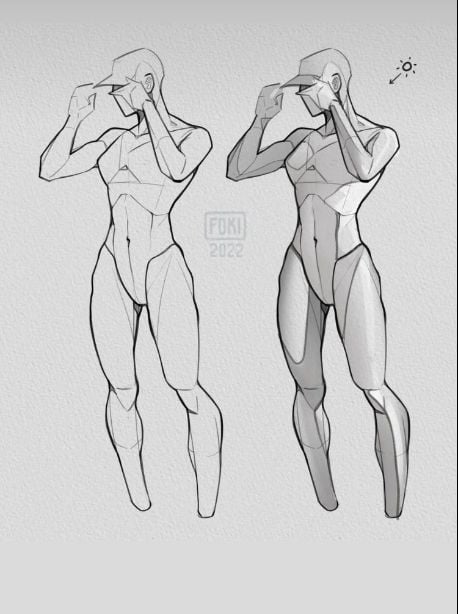

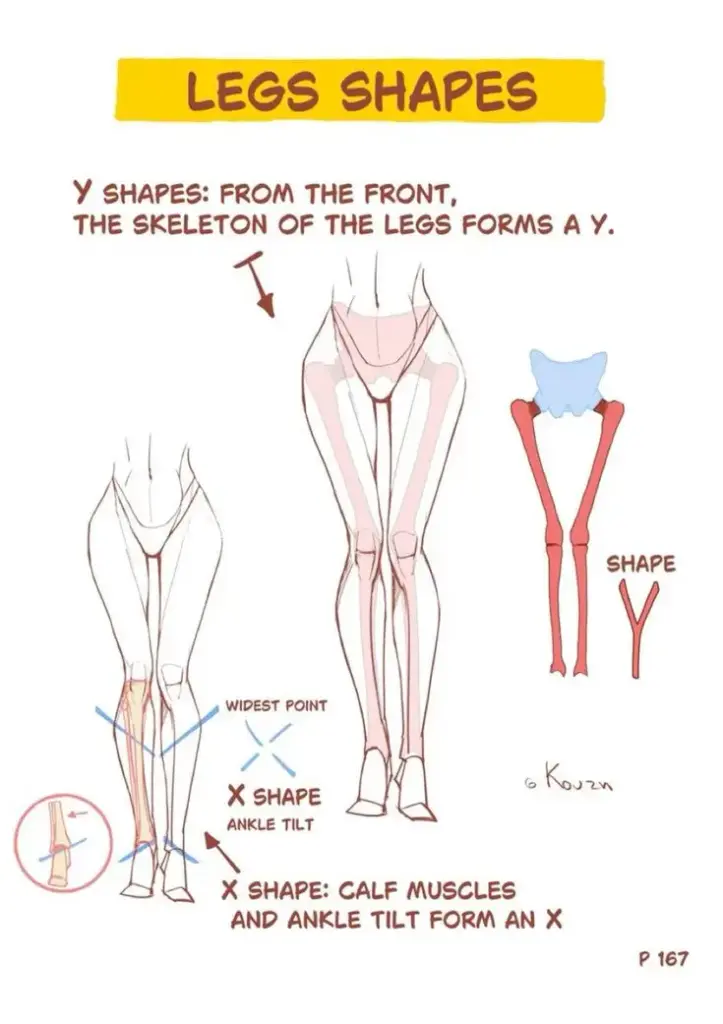

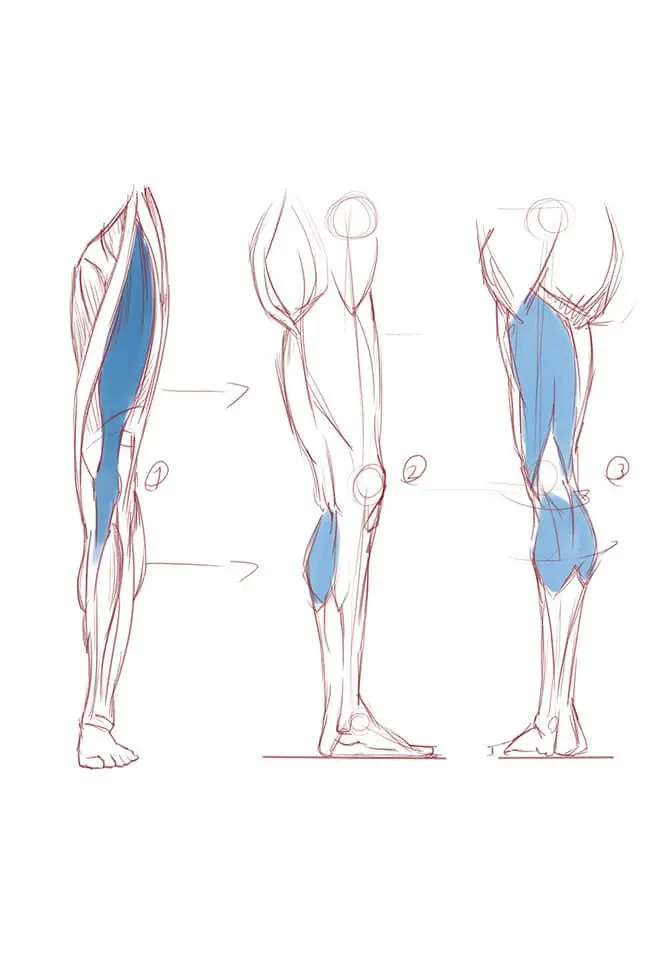

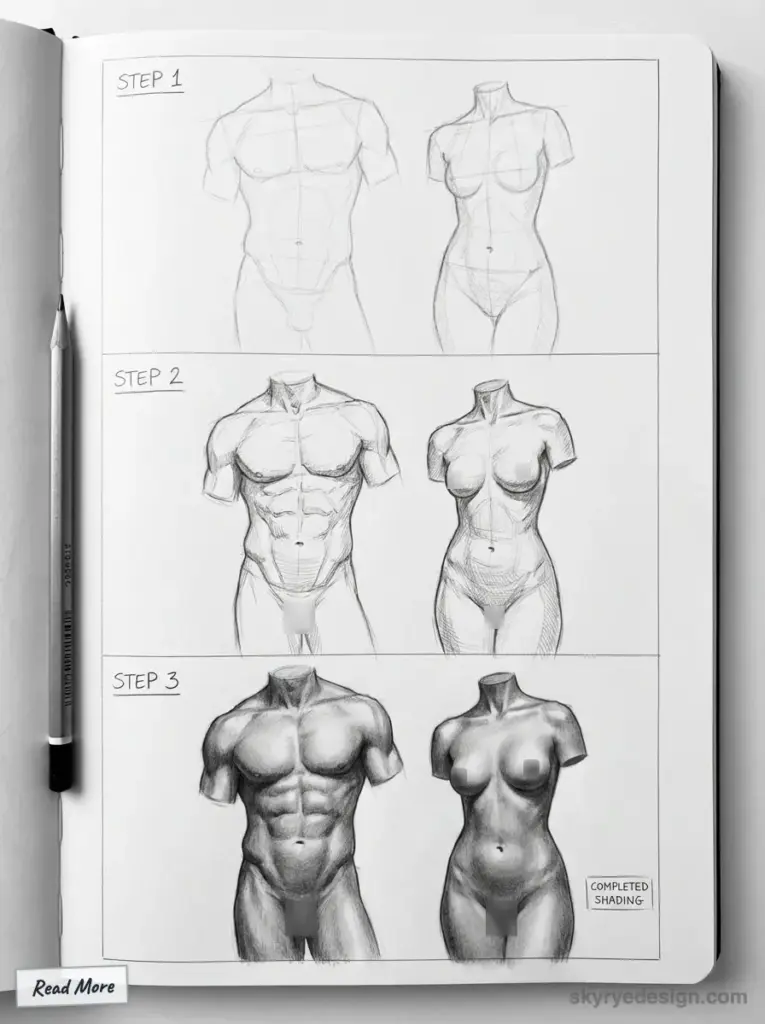

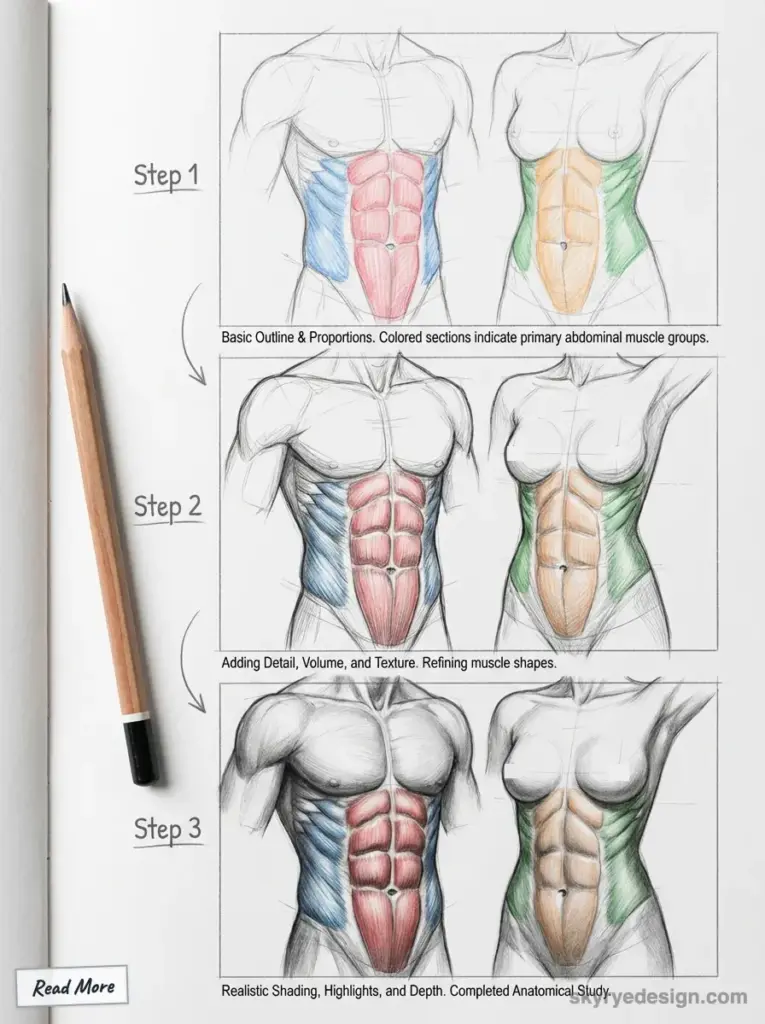

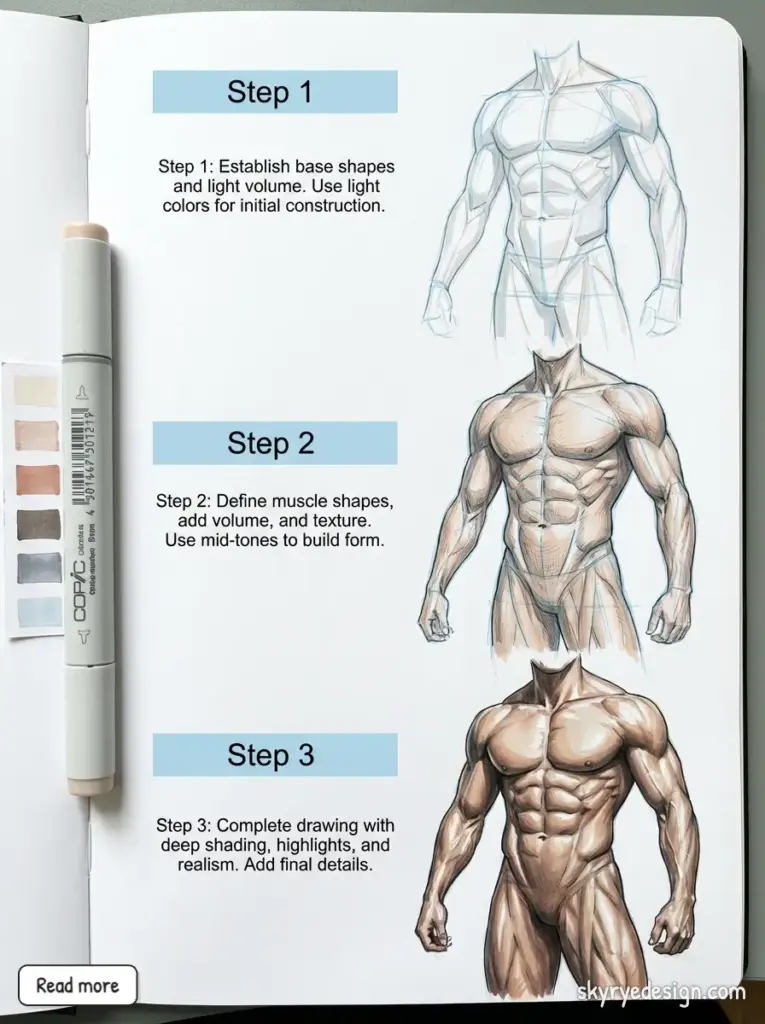

Muscle Distribution (What Actually Changes Visually)

Muscle isn’t just about size — it’s about where mass appears.

General Pattern

- Male bodies

- More mass in chest, shoulders, arms

- Female bodies

- More mass in hips, thighs, glutes

For Artists

- Male figures read stronger when upper-body forms are emphasized.

- Female figures read more natural when lower-body volume is respected.

- Avoid copying bodybuilding anatomy — think in simple mass placement.

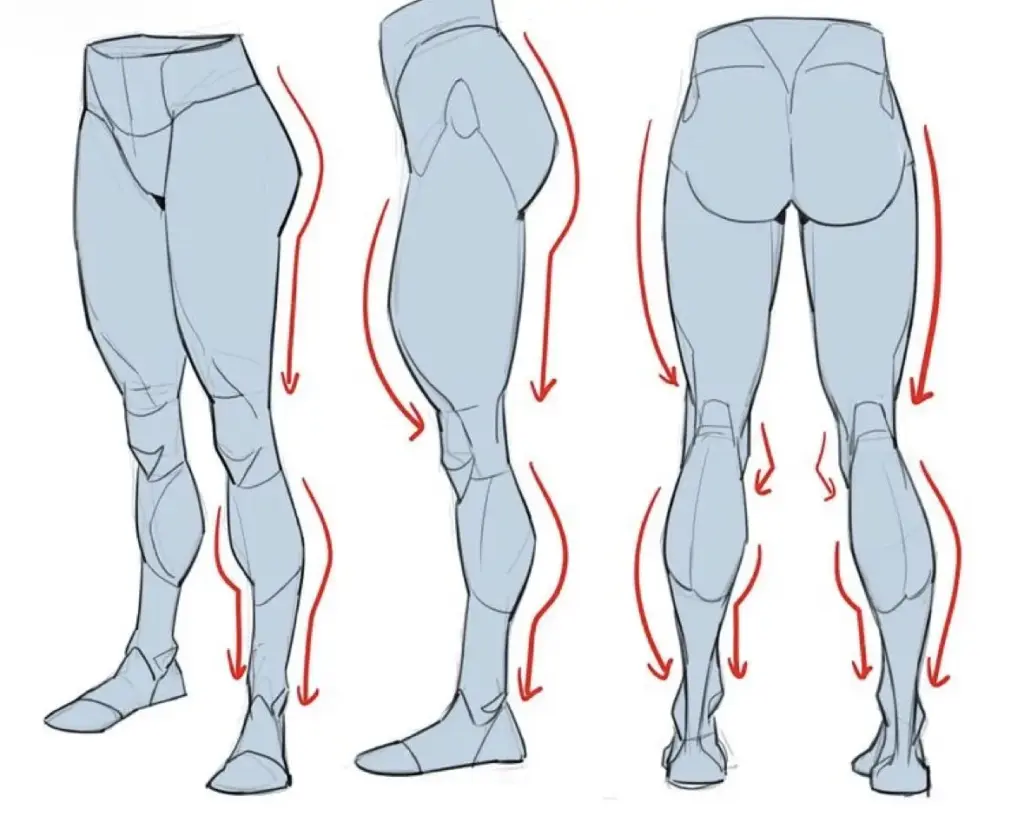

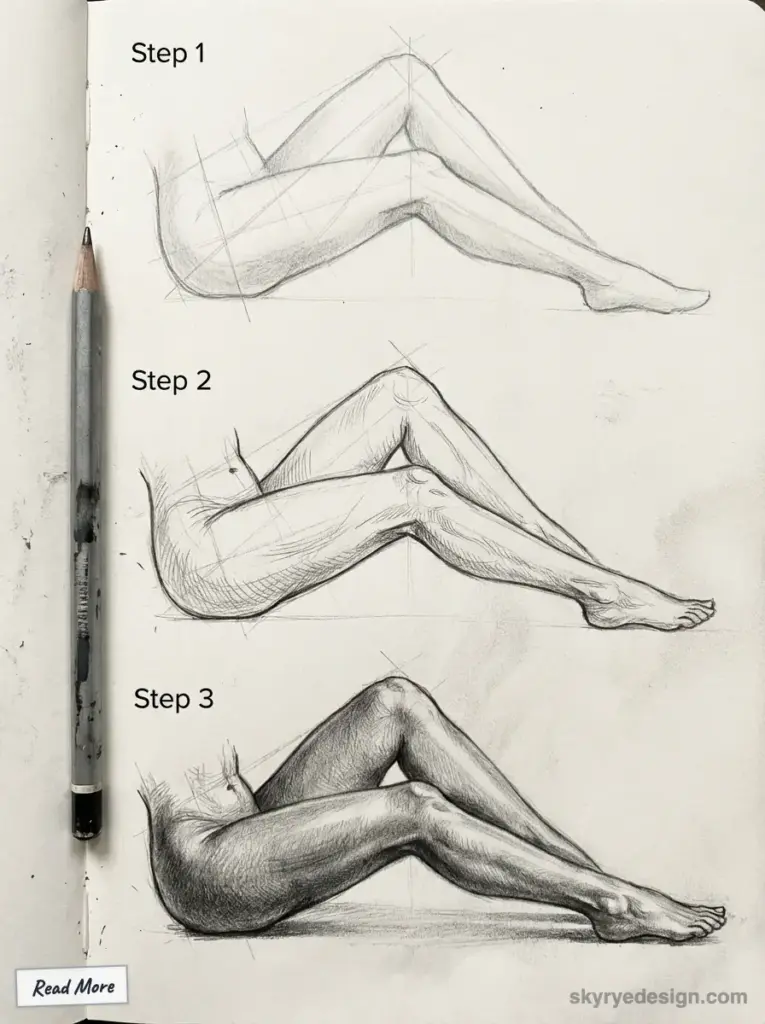

Fat Distribution → Flow of Lines (Very Important)

Forget the medical terms.

For artists, fat distribution matters because it affects line quality.

Visual Difference

- Male bodies

- Straighter lines

- Sharper transitions

- Boxier shapes

- Female bodies

- Softer transitions

- Continuous curves

- S-shaped flow

For Artists

- Use straight lines and angles when blocking male figures.

- Use curved, flowing lines when sketching female figures.

- If your female drawing feels stiff, you’re likely overusing straight lines.

- If your male drawing feels soft, you’re likely overusing curves.

This alone can dramatically improve your sketches.

Waist-to-Hip Relationship (Silhouette Design)

This ratio defines silhouette clarity.

- Male silhouette: more rectangular or inverted trapezoid

- Female silhouette: clearer waist indentation

For Artists

- Step back and check the silhouette only.

- A good silhouette should read clearly without internal details.

- Strong characters often rely on exaggerated but believable ratios.

Legs vs Torso Length

This difference is subtle but powerful.

- Male figures

- Slightly longer legs relative to torso

- Female figures

- Slightly longer torso relative to legs

For Artists

- Longer legs enhance a heroic or dynamic male look.

- A slightly longer torso gives female figures a grounded, elegant feel.

- Use this intentionally in character design, not randomly.

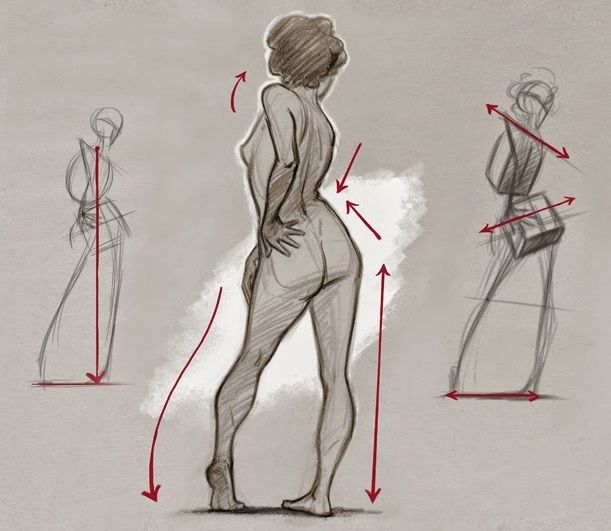

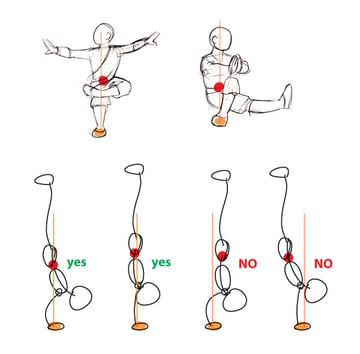

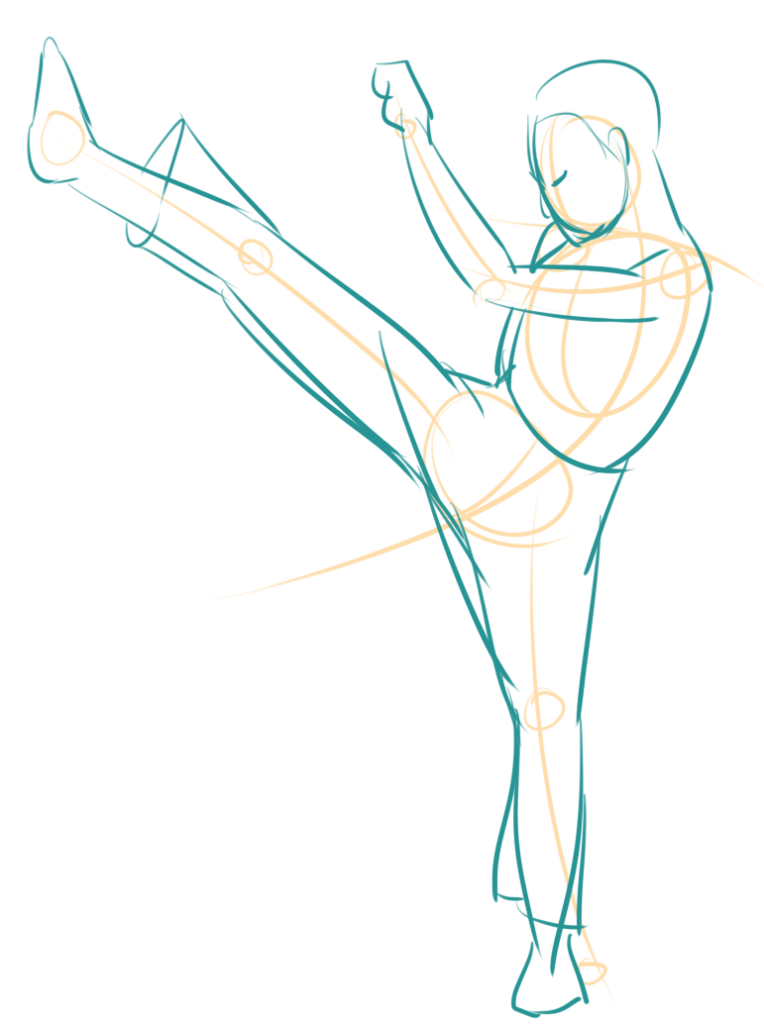

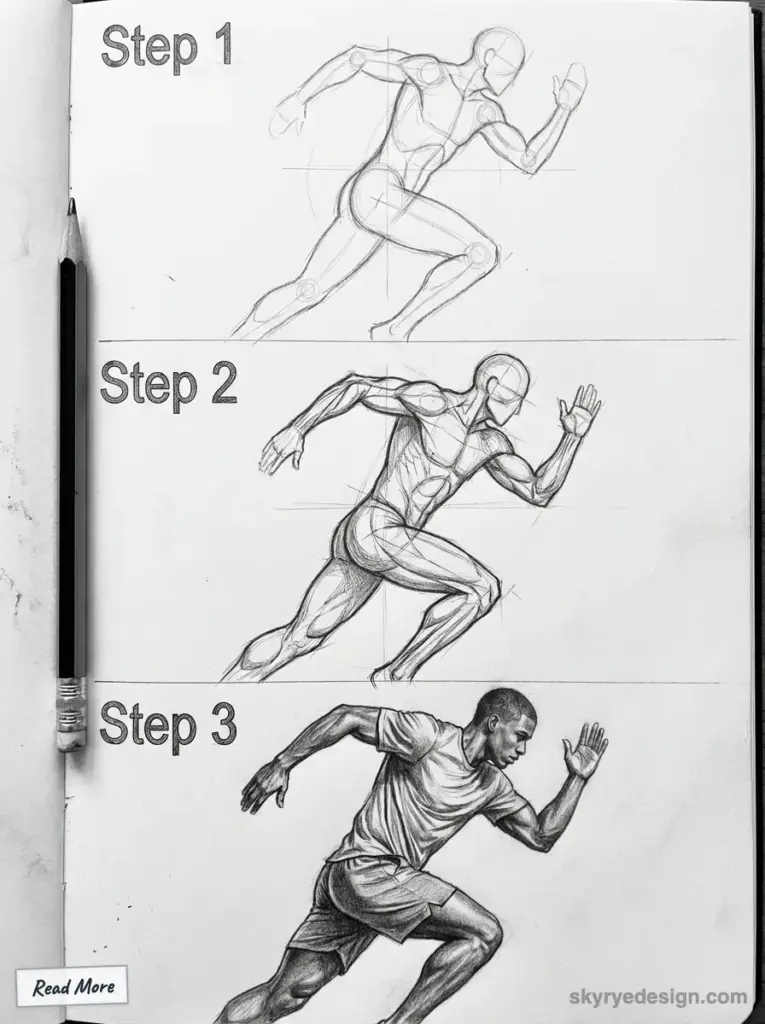

Center of Gravity (Critical for Gesture Drawing)

This is one of the most important concepts for artists.

Structural Difference

- Male center of gravity: higher (closer to chest)

- Female center of gravity: lower (closer to hips)

For Artists

This directly affects your Line of Action.

- Male poses often feel top-heavy, driven by shoulders and chest.

- Female poses feel grounded, with motion flowing through hips and legs.

When drawing gestures:

- Drop the balance point lower for female figures.

- Let male poses initiate movement from the upper torso.

If a pose feels unstable, the center of gravity is usually wrong.

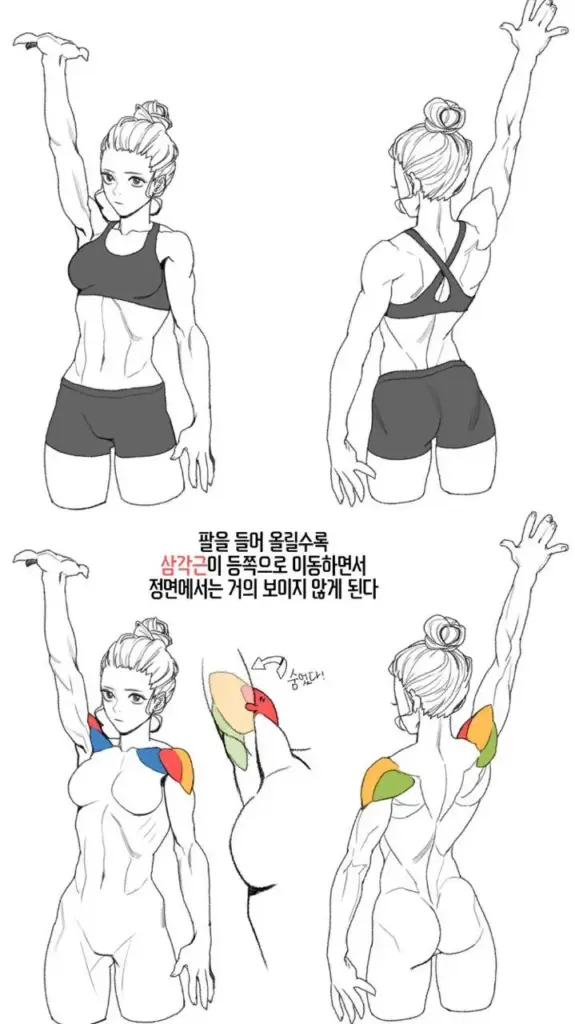

Joint Mobility and Pose Design

Female bodies generally allow more visible flexibility, especially in the hips and spine.

For Artists

- Female poses can comfortably use deeper curves and twists.

- Male poses often look better with controlled, powerful motion.

- This is not a rule — it’s a tendency you can use or break intentionally.

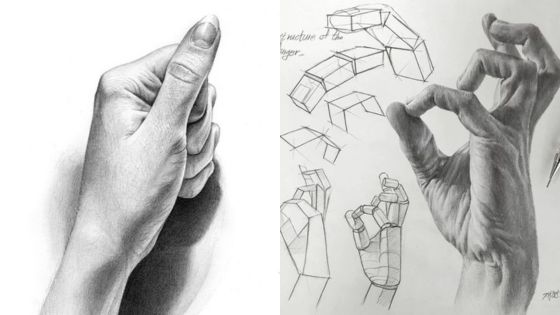

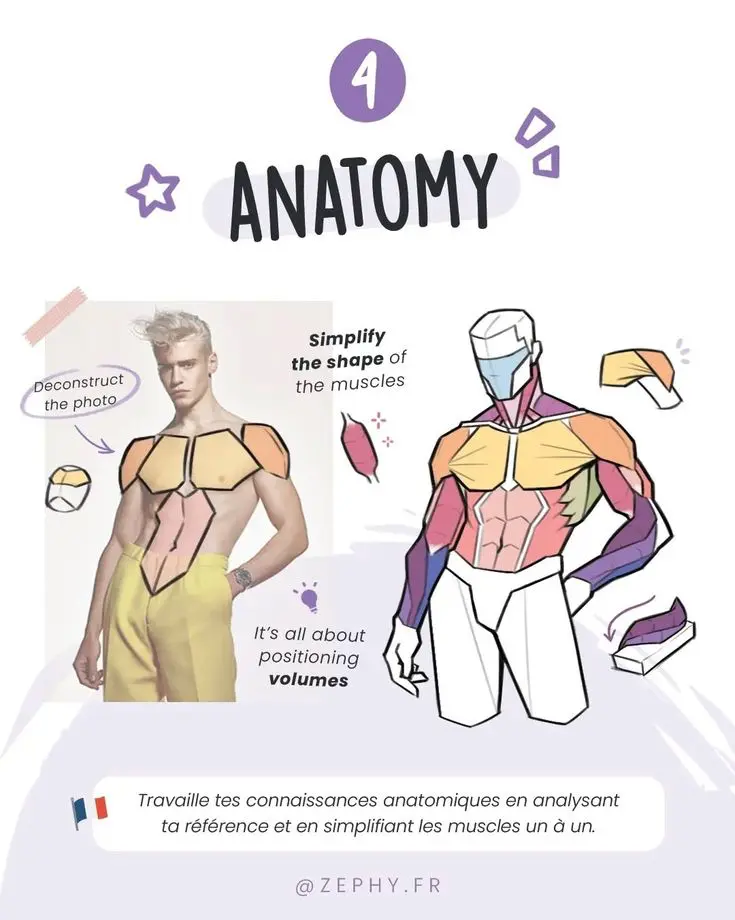

Common Drawing Mistakes (And How to Fix Them)

Mistake 1: Same body, different chest

👉 Fix: Rebuild proportions from the skeleton and head units.

Mistake 2: Over-detailing anatomy

👉 Fix: Simplify into boxes, cylinders, and curves first.

Mistake 3: Ignoring silhouette

👉 Fix: Check readability in solid black.

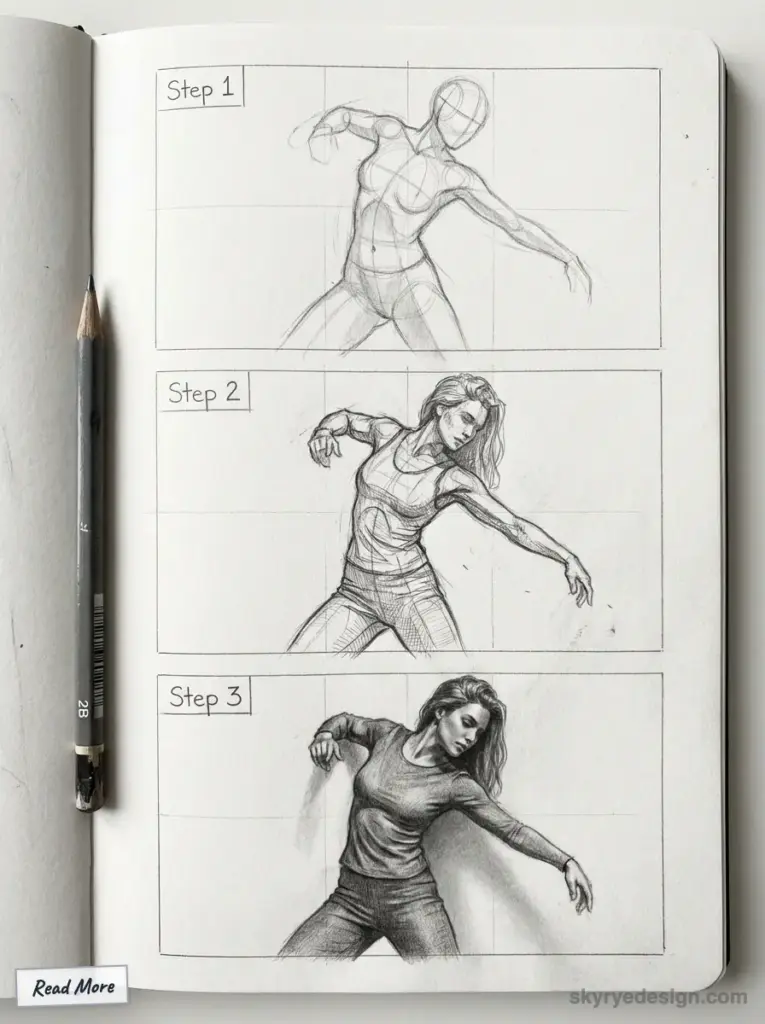

Visual Reference Suggestions (For This Article)

Best visuals to include:

- Male vs female figure at the same height

- Head-unit proportion overlays

- Boxy vs curvy torso simplification

- Line of action comparison

Final Thoughts for Artists

Male vs female body proportions are not about stereotypes — they’re about visual logic.

Once you understand:

- Head units

- Shape language

- Balance and center of gravity

You can stylize, exaggerate, or break the rules on purpose.

That’s when anatomy stops being restrictive — and starts being a tool.

- 0shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest0

- Twitter0

- Reddit0

![How To Draw Male vs Female Bodies [Basic Anatomy 2]](https://skyryedesign.com/wp-content/cache/flying-press/fb4d5c2600da6386c7c15fd60718c817.jpg)