I painted landscapes for three years before someone finally told me the truth: my work looked like colored photographs. Technically accurate. Properly proportioned. Completely lifeless. I was copying nature instead of interpreting it—and that difference explains why some landscape paintings hang in museums while others hang in hotel rooms.

The gap between “competent landscape” and “compelling landscape art” isn’t about talent or expensive materials. It’s about understanding what makes a scene work as a painting rather than as a view. Real masters—from Turner to the Hudson River School to contemporary plein air painters—don’t reproduce what they see. They translate three-dimensional reality into two-dimensional compositions that somehow feel more vivid than the original scene.

- Understanding Landscape Art Fundamentals

- Composition: The Foundation Everything Else Builds On

- Light and Atmosphere: What Separates Good from Great

- Drawing Techniques: Building the Foundation

- Color Theory for Landscape Painters

- Advanced Techniques for Experienced Painters

- Plein Air vs. Studio: Different Approaches

- Materials and Tools

- FAQ

- Conclusion

Here’s what separates landscape snapshots from landscape art: deliberate choices about what to include, what to emphasize, and what to leave out. A photograph captures everything indiscriminately. A painting captures what matters—and that requires understanding composition, light, atmosphere, and the technical skills to execute your vision.

This guide covers landscape art painting from fundamentals through advanced techniques. Whether you’re working in oils, watercolors, or digital media, these principles will help you create landscapes that don’t just record nature but reveal something about it that casual observation misses.

About this guide: These techniques draw from classical training methods, contemporary plein air practice, and over a decade of landscape work across multiple media. The fundamentals remain consistent whether you’re painting the Rocky Mountains or a suburban backyard—it’s all about seeing and interpreting.

Understanding Landscape Art Fundamentals

Before techniques come principles. Landscape art has evolved over centuries, developing specific approaches to composition, light, and atmosphere that distinguish it from mere documentation. Understanding this foundation helps you make better decisions in your own work.

What Makes Landscape Art Different from Landscape Photography

Photography captures a moment exactly as the camera sees it. Painting captures a moment as the artist interprets it. This distinction matters because the human eye and brain process scenes differently than cameras—and effective landscape art leverages those differences.

Key distinctions:

- Selective focus: Paintings can sharpen important areas and soften distractions in ways photographs cannot without heavy editing

- Color interpretation: Artists can push colors toward emotional truth rather than literal accuracy

- Compositional control: Unlike photographers who must work with existing elements, painters can move trees, adjust mountain profiles, and eliminate distracting details

- Atmospheric emphasis: Paintings can exaggerate atmospheric effects that cameras often flatten

Understanding these differences helps you stop trying to reproduce photographs and start creating interpretations that only painting can achieve.

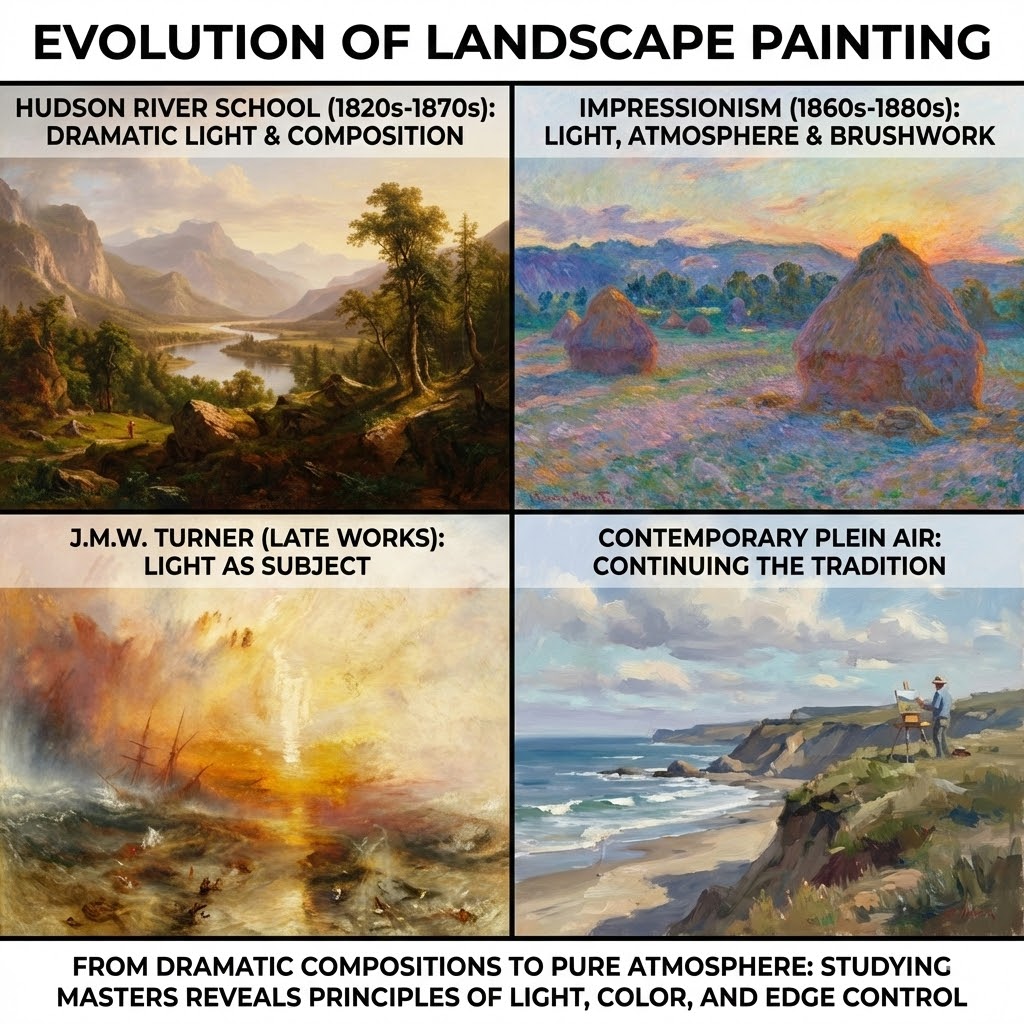

Historical Foundations Worth Studying

Landscape painting has deep roots, and studying masters teaches principles that textbooks often miss:

The Hudson River School (1820s-1870s) mastered dramatic American landscapes by emphasizing light effects and careful composition. Artists like Thomas Cole and Frederic Edwin Church created works that balance grandeur with intimate detail. Study how they handle foreground-to-background transitions.

Impressionists (1860s-1880s) revolutionized landscape painting by prioritizing light and atmosphere over precise detail. Monet’s haystacks and Pissarro’s rural scenes demonstrate how brushwork and color temperature convey time of day more effectively than photographic accuracy.

J.M.W. Turner pushed atmospheric effects further than anyone before, creating landscapes where light itself becomes the subject. His late work dissolves forms into pure atmosphere—study it to understand how far you can push abstraction while maintaining recognizable scenes.

Contemporary plein air painters continue developing these traditions. Artists working outdoors today face the same challenges as their predecessors: capturing fleeting light, simplifying complex scenes, and translating three-dimensional depth onto flat surfaces.

Composition: The Foundation Everything Else Builds On

Composition determines whether a landscape works before you apply a single brushstroke of color. Get composition wrong, and no amount of technical skill saves the painting. Get it right, and even simple execution creates compelling results.

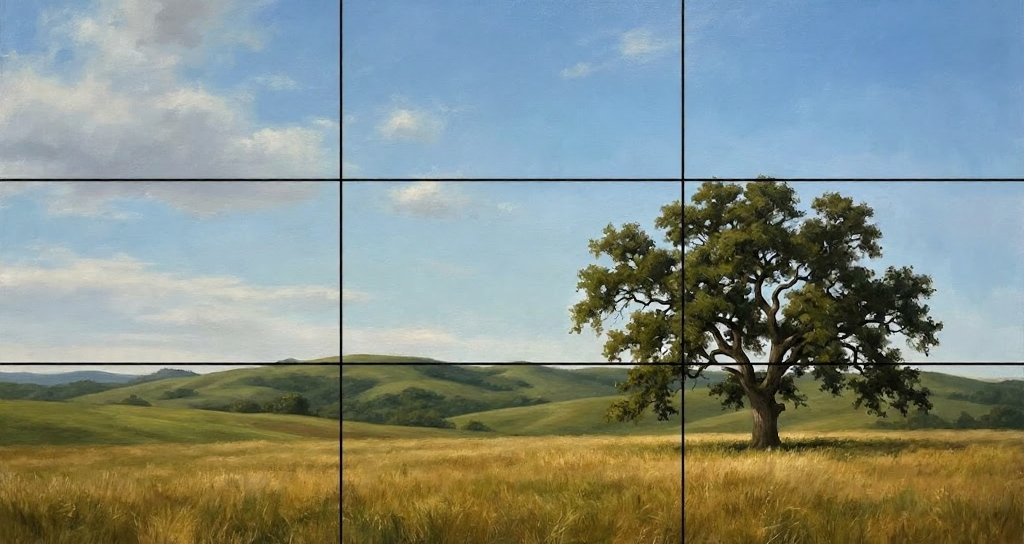

The Rule of Thirds (And When to Break It)

The rule of thirds divides your canvas into a 3×3 grid. Placing key elements along these lines or at their intersections creates natural visual interest. It’s a starting point, not a prison.

Practical application:

- Place the horizon on the upper or lower third line, not centered (centered horizons create static, uninteresting compositions)

- Position your focal point—a distinctive tree, building, or mountain peak—near an intersection point

- Use the grid to check balance: does one section feel overloaded while another feels empty?

When to break it: Centered compositions work for symmetrical subjects like reflections in calm water. Extreme asymmetry (horizon at 1/5 or 4/5) creates drama for threatening skies or vast open spaces. Rules are tools, not laws.

Leading Lines and Visual Flow

Your viewer’s eye enters the painting somewhere and travels through it. Control that journey. Leading lines—rivers, paths, fences, ridgelines—guide the eye toward your focal point.

Effective leading line placement:

- Enter from corners or edges, not the center

- Curve toward the focal point rather than pointing directly at it (direct lines feel aggressive)

- Vary line weights: thick/dark lines advance, thin/light lines recede

- Avoid lines that lead the eye out of the painting or into corners

Common mistake: Random line placement that scatters attention. Every significant line should serve the composition by either leading toward the focal point or framing it.

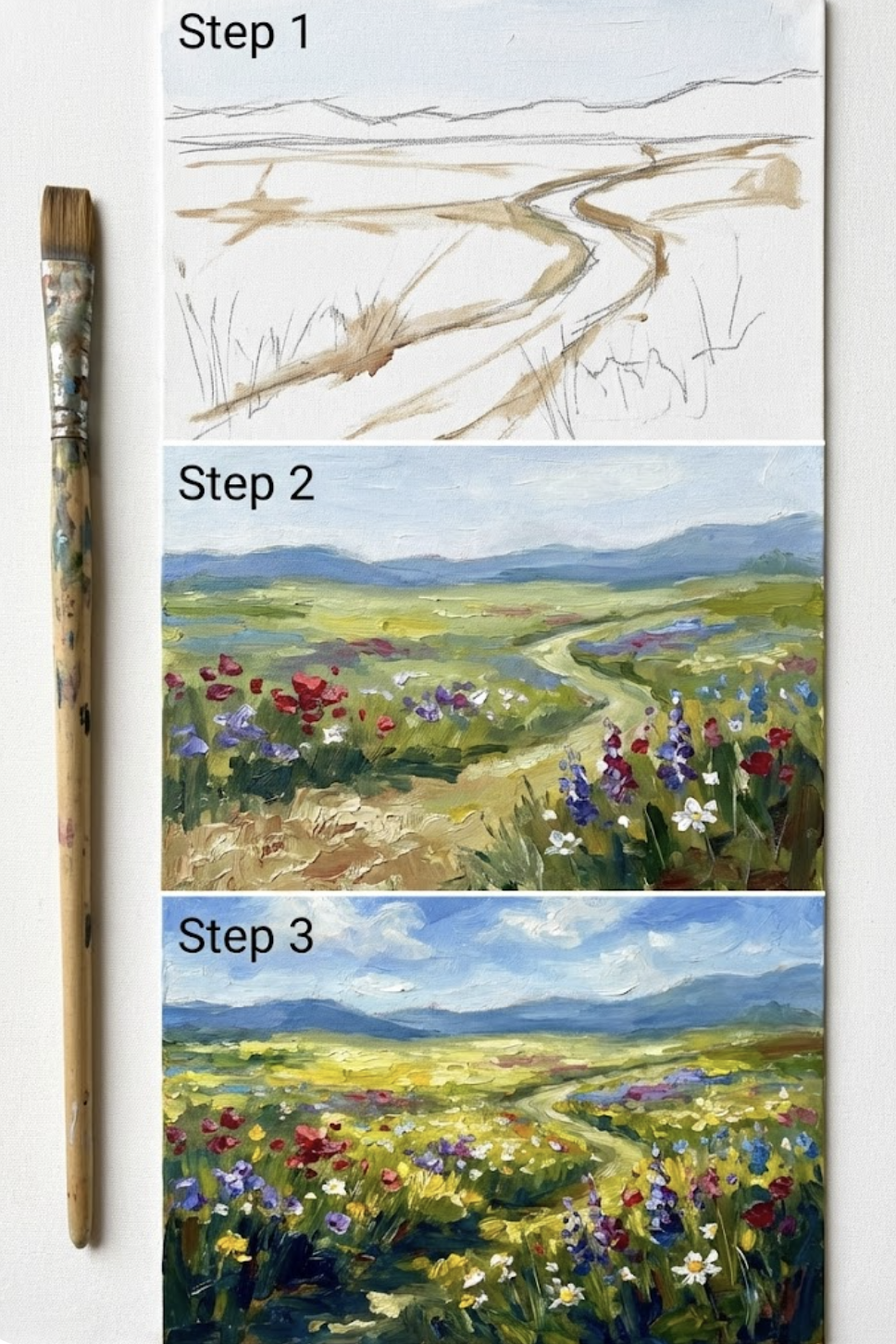

Foreground, Middle Ground, Background

Three-zone composition creates depth. Each zone requires different treatment:

Foreground: Highest detail, strongest contrast, warmest colors, sharpest edges. This zone establishes scale and invites the viewer into the scene. Include something interesting—rocks, wildflowers, a weathered fence—to anchor the composition.

Middle ground: Moderate detail, moderate contrast. This zone typically contains your focal point: the cottage, the distinctive tree, the mountain peak. Give it enough detail to read clearly without competing with foreground interest.

Background: Lowest detail, lowest contrast, coolest colors, softest edges. Mountains, distant trees, and sky recede through atmospheric perspective. Overworking the background is the most common beginner mistake—keep it simple.

Light and Atmosphere: What Separates Good from Great

Light transforms ordinary scenes into extraordinary subjects. The same meadow looks completely different at dawn versus noon versus sunset. Understanding how light works—and how to paint it—distinguishes competent landscapes from compelling ones.

The Golden Hour Myth (And What Actually Matters)

Yes, golden hour light is beautiful. But chasing “perfect” lighting conditions misses the point. Every lighting situation offers opportunities if you understand what to emphasize.

Midday light: Often dismissed as “flat,” but it offers clarity and saturated local colors. Use strong cast shadows to create interest. Midday works well for scenes where color contrast matters more than atmospheric drama.

Overcast light: Diffused and soft, with subtle gradations. Perfect for intimate scenes, forest interiors, and subjects where you want color harmony without harsh shadows. The lack of strong directional light lets form and detail shine.

Golden hour light: Yes, it’s beautiful—warm tones, long shadows, dramatic atmosphere. But it changes fast, so know what you want before you start. Plan your composition and values in advance; don’t waste golden light on decision-making.

Blue hour and twilight: Cool tones, reduced contrast, increasing atmosphere. Excellent for mood and mystery, but requires confident value control as details disappear.

What actually matters: Not the time of day, but understanding the light’s direction, color temperature, and intensity—and how those factors affect your specific subject.

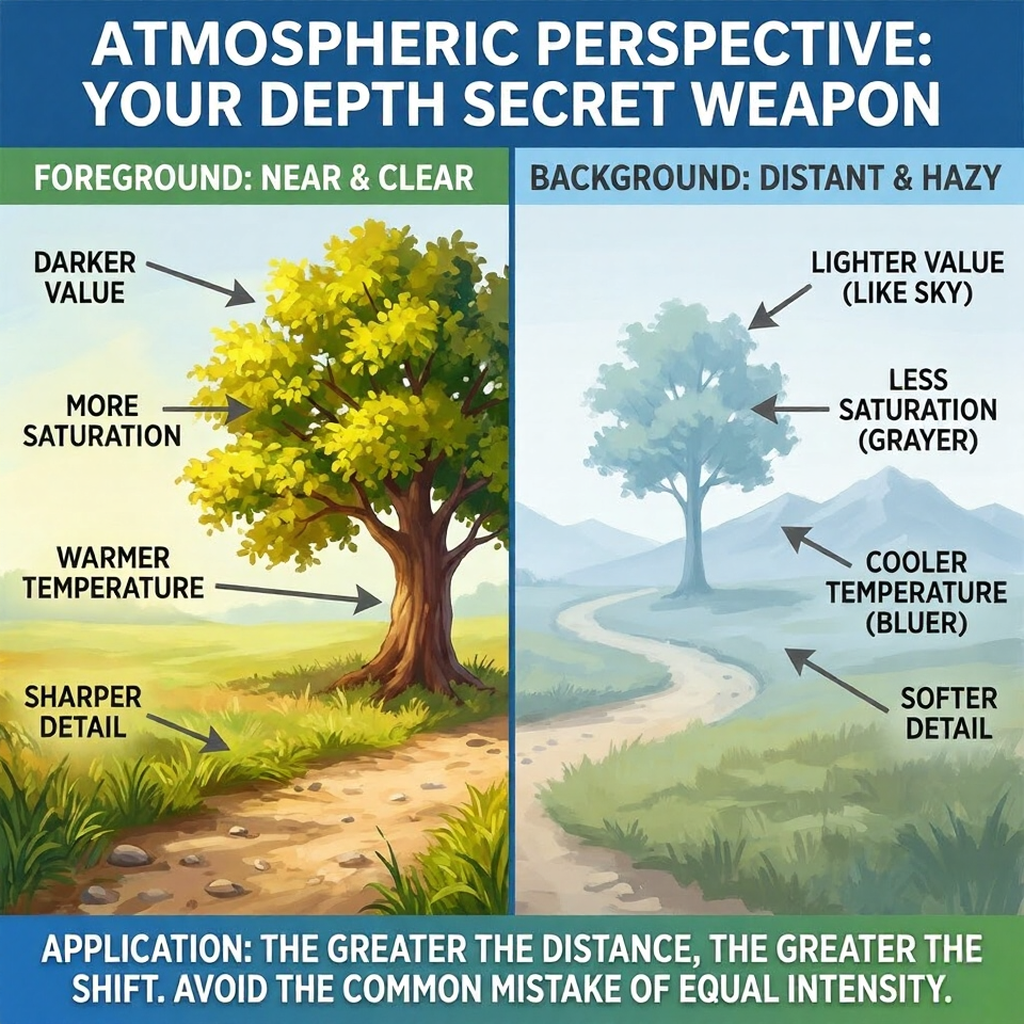

Atmospheric Perspective: Your Depth Secret Weapon

Atmosphere between you and distant objects changes how those objects appear. This phenomenon—atmospheric perspective—is your most powerful tool for creating depth.

The rules:

- Value shift: Distant objects appear lighter (approach the sky value)

- Saturation shift: Distant objects appear less saturated (grayer)

- Color temperature shift: Distant objects appear cooler (more blue)

- Detail shift: Distant objects show less detail, softer edges

Application: A green tree in the foreground might be dark, saturated yellow-green with crisp edges. The same tree species in the background should be lighter, grayer, bluer, and softer. The distance between them determines how much these values shift.

Common mistake: Painting distant mountains with the same intensity as foreground elements. This flattens the scene and destroys the illusion of depth.

Creating Mood Through Light

Light doesn’t just illuminate—it communicates emotion. Different lighting scenarios evoke different responses:

High-key lighting (predominantly light values): Optimistic, airy, spacious. Good for open meadows, beaches, snow scenes.

Low-key lighting (predominantly dark values): Dramatic, moody, intimate. Good for forests, storms, twilight scenes.

High contrast: Dynamic, energetic, attention-grabbing. Strong sunlight creating bright highlights and deep shadows.

Low contrast: Peaceful, subtle, contemplative. Overcast days, fog, mist.

Choose your value structure before you start painting. Mixing approaches creates confusion—commit to a mood and execute it consistently.

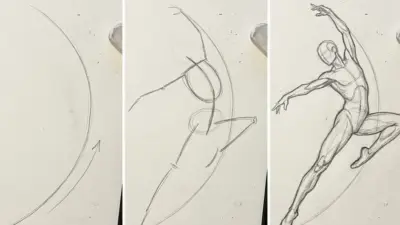

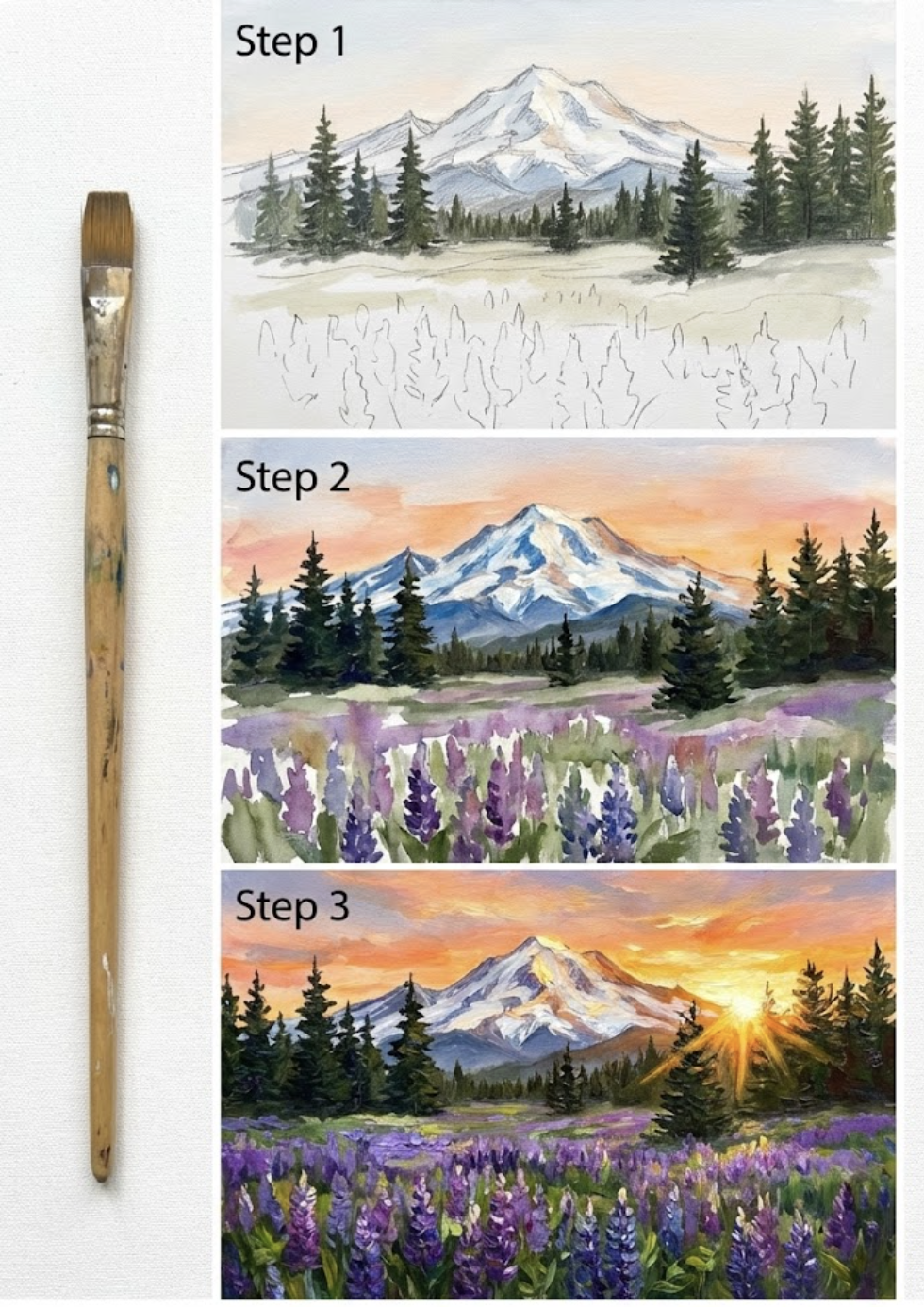

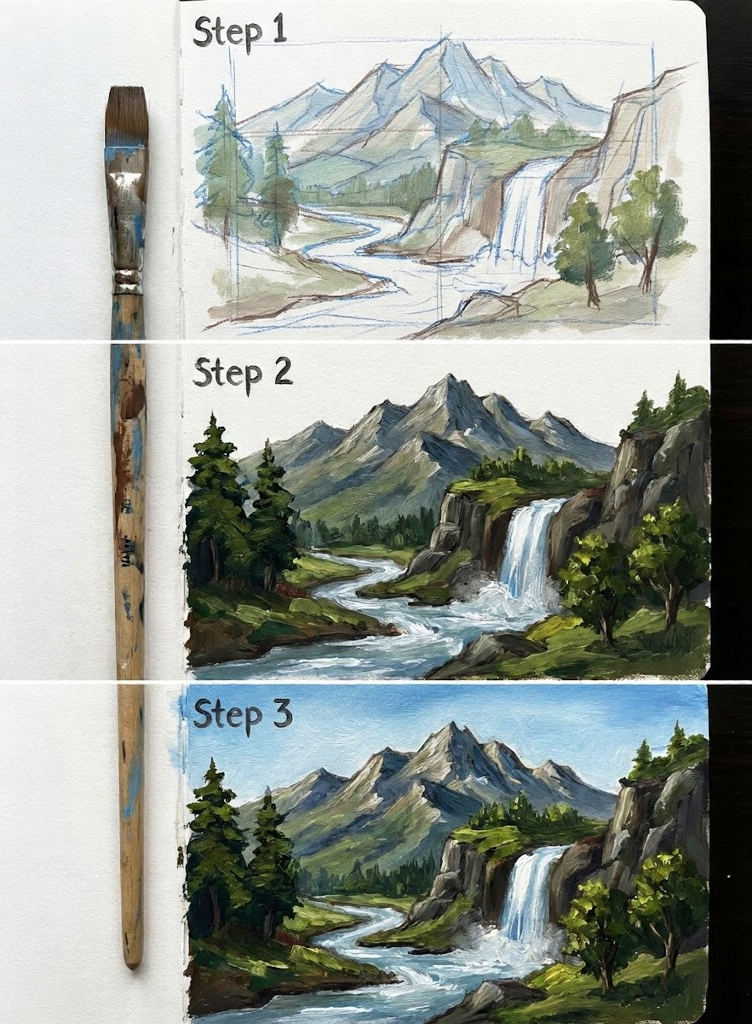

Drawing Techniques: Building the Foundation

Before paint comes drawing. Solid underdrawing ensures proper proportions, composition, and value structure. Rushing this stage causes problems that no amount of painting can fix.

Thumbnail Sketches: Your Most Powerful Tool

Small, quick compositional sketches (2″×3″ or so) let you test ideas before committing to a full painting. Complete 3-5 thumbnails for every scene before choosing the strongest composition.

What to establish in thumbnails:

- Overall value structure (light, medium, dark masses)

- Horizon placement

- Focal point location

- Major shapes and their relationships

- Format (horizontal, vertical, square)

Time investment: 2-5 minutes per thumbnail. This tiny investment prevents hours of struggling with a composition that was doomed from the start.

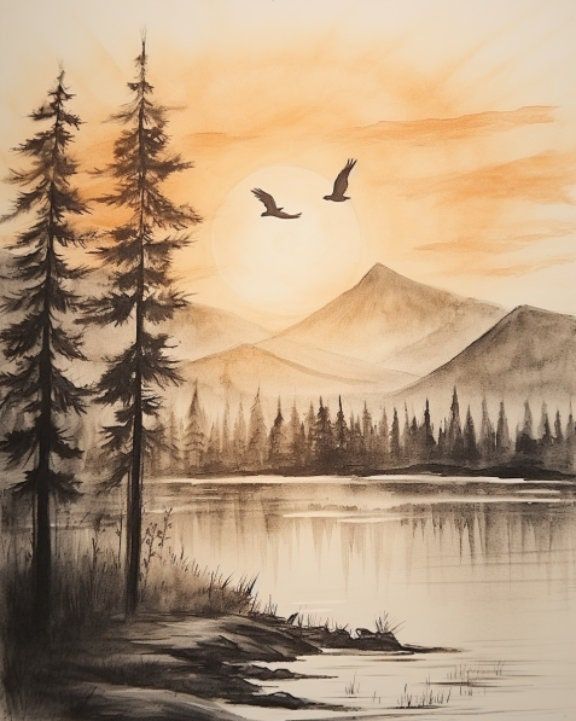

Value Studies: Painting Without Color

A value study is a small (4″×6″ or so) monochromatic painting that establishes your light and dark pattern before introducing the complexity of color. Use three to five values maximum.

Why value studies matter: Color can deceive you—a bright yellow might be the wrong value even though it’s the “right” color. By solving value relationships first in grayscale, you ensure your painting will read correctly when you add color.

Process:

- Block in your darkest darks

- Establish your lightest lights

- Fill middle values, simplifying shapes

- Check: does the composition read clearly in grayscale? If not, adjust before adding color.

Shading Techniques for Drawings

If working in pencil or charcoal, master these techniques for creating form and atmosphere:

Hatching: Parallel lines creating value. Closer lines = darker values. Line direction can suggest form (following contours) or remain uniform for flat values.

Cross-hatching: Layered hatching in different directions. Creates richer darks and more complex textures than simple hatching.

Stippling: Dots creating value through density. Time-consuming but creates unique textural effects, especially useful for rocky surfaces or foliage.

Blending: Smooth transitions using stumps, tortillons, or fingers. Creates atmospheric effects and soft gradations but can look overworked if used everywhere.

Combine techniques based on the surface you’re depicting: hatching for grass, stippling for rocky textures, blending for sky and distant atmosphere.

Color Theory for Landscape Painters

Color is where many landscape painters struggle. The solution isn’t memorizing color wheels—it’s understanding how color relationships create harmony, depth, and emotional impact.

Building a Landscape Palette

You don’t need dozens of colors. A limited palette forces color mixing, which creates harmony. Start with:

Warm/cool pairs:

- Warm yellow (cadmium yellow) / Cool yellow (lemon yellow)

- Warm red (cadmium red) / Cool red (alizarin crimson)

- Warm blue (ultramarine) / Cool blue (cerulean or phthalo)

Earth tones: Yellow ochre, burnt sienna, burnt umber. These form the backbone of most landscape palettes.

White: Titanium white for opacity, or mix with zinc white for more transparency.

Optional: A premixed green (viridian or chromium oxide green) saves mixing time, but isn’t essential—you can mix all greens from yellows and blues.

This basic palette can create any landscape color through mixing. More colors don’t mean better paintings—they often mean muddy, unharmonious results.

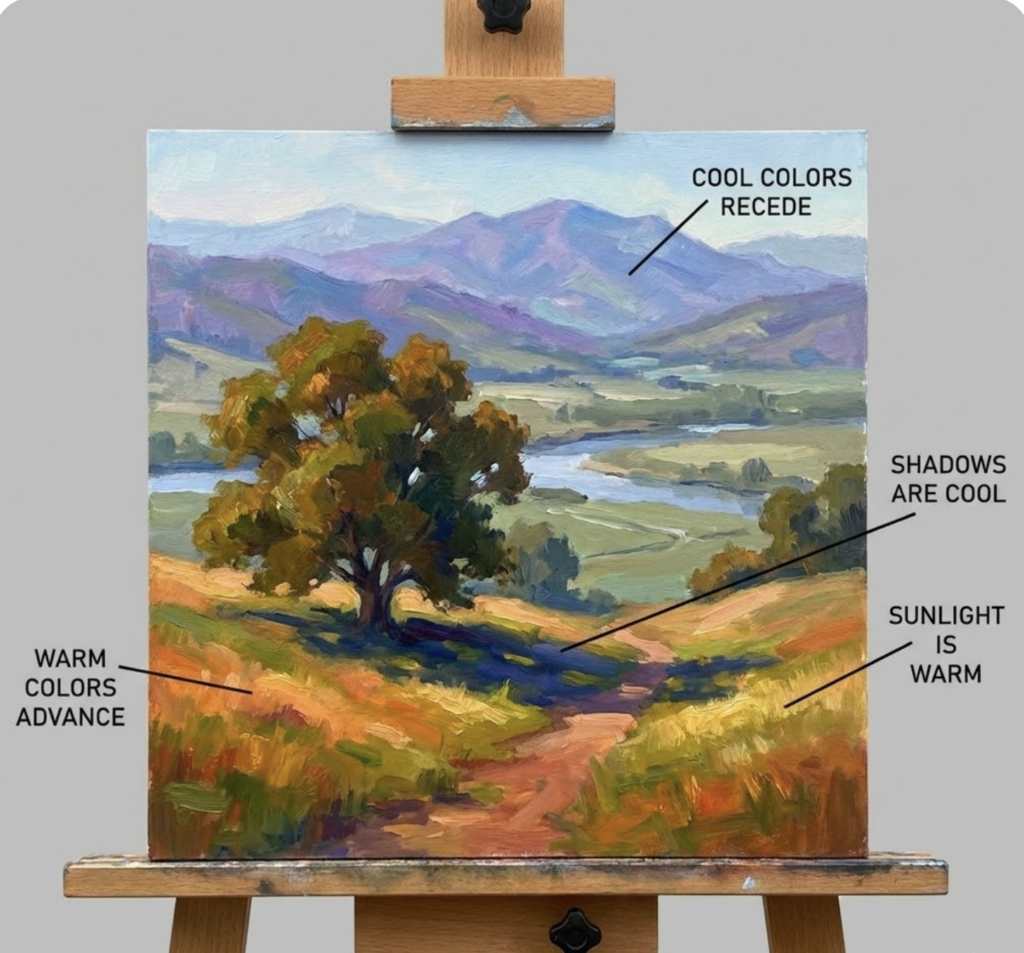

Color Temperature and Spatial Relationships

Color temperature (warm vs. cool) creates depth as effectively as value:

- Warm colors advance: Reds, oranges, yellows come forward

- Cool colors recede: Blues, cool greens, violets fall back

Application: Keep foreground colors relatively warm (even if the local color is “green,” warm it with yellow). Push background colors cooler (add blue, reduce saturation). This temperature gradient reinforces atmospheric perspective.

Shadow colors: Shadows aren’t just darker—they’re usually cooler and more chromatic than you expect. A shadow on warm grass contains cool blues and violets. Observe this in nature and resist the urge to just add black.

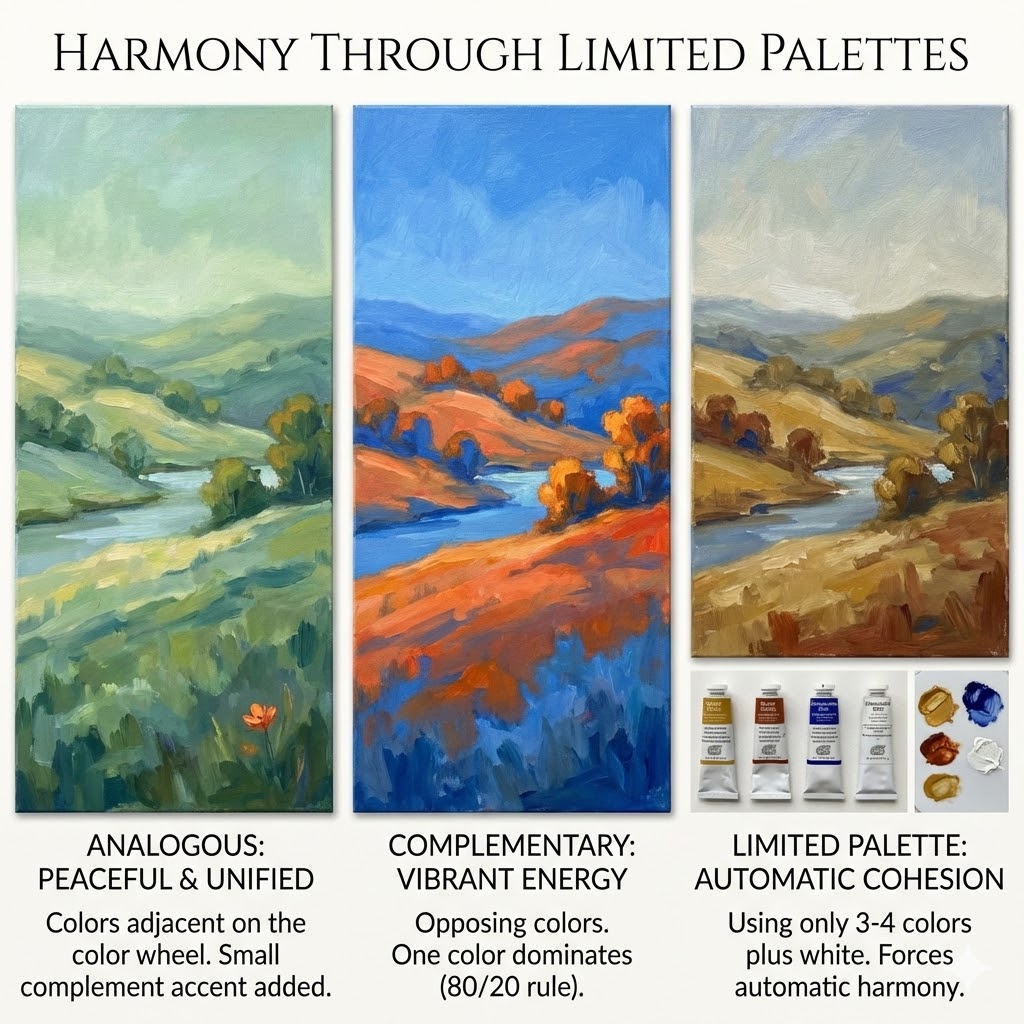

Harmony Through Limited Palettes

Color harmony comes from relationships, not from using “harmonious colors.” Three approaches:

Analogous harmony: Colors adjacent on the color wheel (yellow-green-blue, or orange-red-violet). Creates peaceful, unified scenes. Risk: monotony. Solution: add a small complement accent.

Complementary harmony: Opposing colors (orange/blue, red/green, yellow/violet). Creates vibrant energy. Risk: garish if overused. Solution: let one color dominate (80/20 rule).

Limited palette harmony: Using only 3-4 colors plus white forces all mixed colors to share pigments, creating automatic harmony. This is the simplest path to cohesive color.

Advanced Techniques for Experienced Painters

Once fundamentals are solid, these advanced approaches push your landscape work further.

Painting Atmosphere (Not Just Showing It)

Atmosphere isn’t just value reduction in the distance—it’s an active presence throughout the scene. Advanced atmospheric painting includes:

Aerial haze: The bluish film between you and distant objects. Paint it as a visible layer, not just an effect on the distant objects themselves.

Dust and moisture: Dry, dusty conditions create warm atmospheric haze. Humid conditions create cool haze. Match your atmospheric color to your scene’s conditions.

Light rays: Crepuscular rays (sunbeams through clouds or trees) are atmosphere made visible. Paint the glow, not just the beam edges.

Reflected light within shadows: Atmosphere bounces light into shadow areas, especially from the sky. Shadow areas often contain surprising amounts of color from surrounding surfaces.

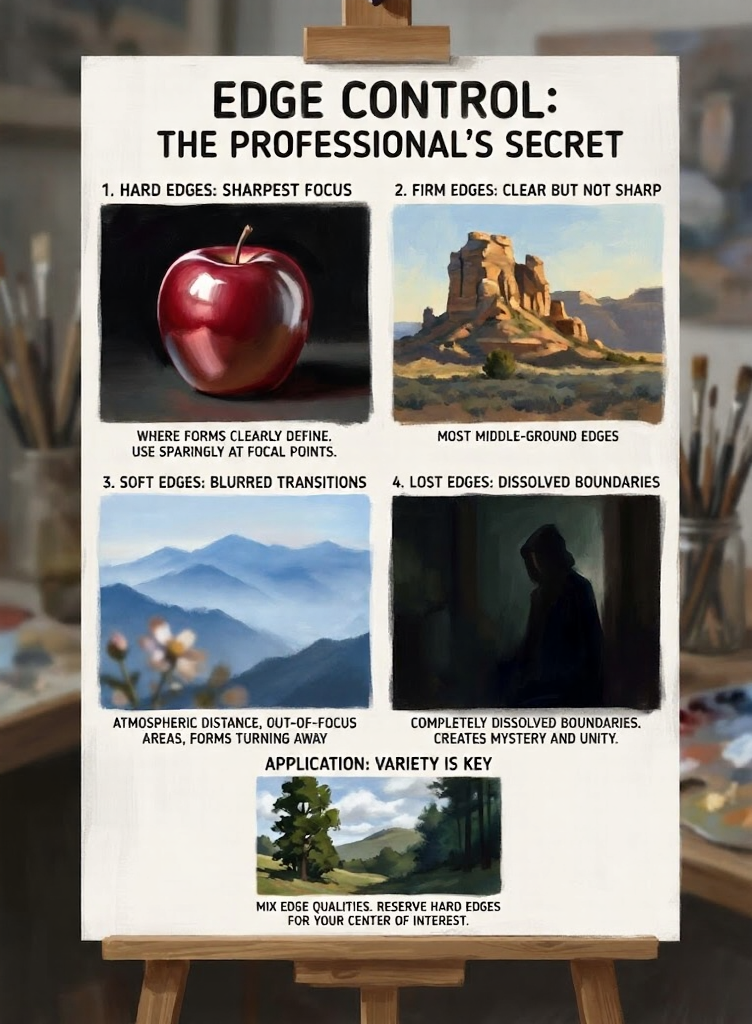

Edge Control: The Professional’s Secret

Edges—where shapes meet—communicate focus, atmosphere, and depth. Edge control separates advanced work from competent work.

Four edge types:

- Hard edges: Sharpest focus, where forms clearly define against each other. Use sparingly at focal points.

- Firm edges: Clear but not razor-sharp. Most middle-ground edges.

- Soft edges: Blurred transitions. Atmospheric distance, out-of-focus areas, forms turning away.

- Lost edges: Completely dissolved boundaries where adjacent values merge. Creates mystery and unity.

Application: Your painting needs variety. All hard edges feel harsh and artificial. All soft edges feel foggy and unfocused. Mix edge qualities, reserving hard edges for your center of interest.

Simplification and Abstraction

The further you advance, the more you simplify. Beginners try to paint every leaf; masters suggest forests with a few well-placed strokes.

Simplification strategies:

- Squinting: Reduces detail to major value shapes. Paint what you see when squinting.

- Shape grouping: Combine similar-value areas into unified shapes. Five trees become one tree mass.

- Selective detail: High detail at focal point, decreasing detail everywhere else.

- Suggestive brushwork: Let brushstrokes imply texture rather than rendering every element.

The goal: Make the viewer’s eye do work. A few well-placed suggestions communicate “forest” more effectively than exhaustive rendering—and leave room for the viewer’s imagination.

Plein Air vs. Studio: Different Approaches

Both outdoor and studio landscape painting have strengths. Many artists combine them.

Plein Air Advantages

Painting on location captures qualities impossible to replicate from photographs:

- Accurate color relationships: Cameras lie about color. Your eye doesn’t.

- Immersive observation: Being in the scene helps you understand depth, scale, and atmosphere

- Time pressure: Limited light forces decision-making and prevents overworking

- Fresh brushwork: Necessity breeds efficiency and confident strokes

Studio Advantages

Working from studies and reference in controlled conditions allows:

- Extended time: Complex compositions require more time than changing light allows

- Large scale: Practical considerations make large work difficult outdoors

- Refinement: Time to develop and adjust without weather pressure

- Combination: Synthesize multiple studies into single compositions

Best Practice: Combine Both

The most effective approach uses plein air studies to gather information and studio time to develop finished work. Small outdoor paintings capture light and color notes; larger studio paintings develop those observations into resolved compositions.

Materials and Tools

The right materials support your vision without getting in the way.

Essential Supplies

Brushes: A few quality brushes beat many cheap ones. For landscapes: large flat for blocking, medium flat and round for development, small round for details. Bristle for oils, synthetic for acrylics and watercolors.

Surface: Canvas (stretched or panel) for oils/acrylics, quality paper for watercolors. Toned surfaces (gray or warm neutral) simplify value judgments compared to stark white.

Palette: Enough mixing room matters more than material. Glass, wood, or plastic all work—just ensure adequate space.

Medium: For oils, a simple 50/50 linseed oil/odorless mineral spirits mixture handles most needs. Avoid overcomplicating mediums as a beginner.

Field vs. Studio Setups

Plein air essentials: Pochade box or French easel, limited palette (fewer tubes to carry), small panels, hat and umbrella for sun/rain.

Studio essentials: Solid easel, good lighting (north light ideal, or color-balanced artificial), comfortable standing/sitting arrangement, adequate palette space.

FAQ

How do I stop my landscapes from looking flat?

Flat landscapes usually lack atmospheric perspective and value structure. Ensure distant objects are lighter, cooler, and less detailed than foreground objects. Check your value study—if it reads flat in grayscale, color won’t fix it.

Should I paint from photographs or life?

Both, with awareness of their limitations. Photographs flatten values and distort colors, so use them as reference rather than copying exactly. Plein air work trains your eye but limits time and scale. Ideally, gather information outdoors and develop paintings using multiple references.

How long should a landscape painting take?

As long as it needs. Small plein air studies might take 30 minutes to 2 hours. Complex studio paintings might take weeks. Speed comes with experience, but finished is better than fast.

What’s the most common landscape painting mistake?

Overworking the background. Beginners paint distant mountains with the same detail and contrast as foreground elements, destroying the illusion of depth. Simplify aggressively as elements recede.

How do I choose what to paint?

Look for strong value patterns, interesting light, or emotional resonance. A “boring” subject with beautiful light beats a “dramatic” subject with flat lighting. Trust what excites you—that excitement transfers to the painting.

Conclusion

Landscape art painting comes down to interpretation, not reproduction. The masters didn’t copy nature more accurately than you can—they understood what to emphasize, what to simplify, and how to translate three-dimensional reality into compelling two-dimensional compositions.

Every technique in this guide serves that translation process: composition directs attention, value structure creates readability, atmospheric perspective builds depth, color relationships evoke mood, and edge control guides the eye. These aren’t separate skills—they’re interconnected aspects of a single goal: making paintings that reveal something about nature that casual observation misses.

This week: Complete five thumbnail sketches and one value study before your next painting. Don’t touch color until you’ve solved composition and value in grayscale.

This month: Focus on atmospheric perspective. In every painting, deliberately push distant elements lighter, cooler, and softer. Exaggerate the effect until you understand it; you can pull back later.

Ongoing: Study the masters mentioned in this guide. Not to copy their work, but to understand their decisions. Why did Turner dissolve his backgrounds? How did Church handle foreground-to-background transitions? What can Monet teach you about color temperature?

The landscape outside your window isn’t waiting for a better painter—it’s waiting for a painter who can see it clearly and interpret it honestly. That painter develops through deliberate practice, accumulated observation, and thousands of paintings that each teach something about the one fundamental challenge: making flat surfaces suggest infinite depth, changing light, and the living presence of natural spaces.

Your next landscape is practice for the one after. Start painting.

- 950shares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest950

- Twitter0

- Reddit0