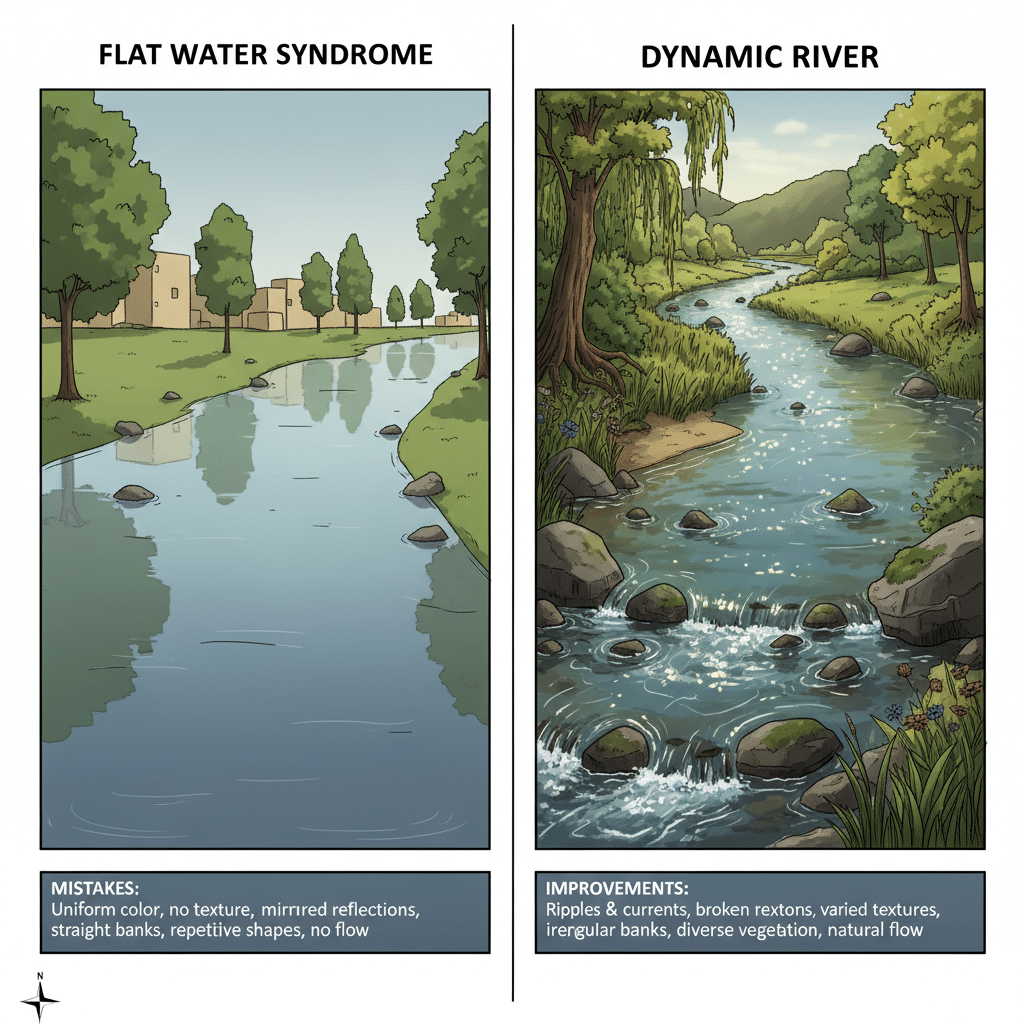

My early river drawings looked like someone had poured blue paint down a highway. Two parallel lines converging in the distance, colored in with uniform blue, and some wavy lines that were supposed to be “ripples.” They had the basic shape of a river but none of the life. They looked like diagrams, not water.

The problem wasn’t my drawing skills—it was my understanding of what makes a river look like a river. I was drawing the idea of a river instead of depicting how rivers actually behave. Rivers flow. They respond to terrain. They reflect, refract, and constantly change speed. Water near the banks acts differently than water in the center. The surface tells you what’s happening underneath.

Here’s what separates a convincing river from a blue road: rivers are defined by movement and interaction, not by shape and color. The banks aren’t just borders—they influence flow. Rocks aren’t just obstacles—they create patterns. Light doesn’t just color the surface—it reveals depth and speed. Once you understand what rivers do, drawing them becomes about depicting behavior rather than filling in a shape.

This guide breaks down river drawing into its component problems: perspective that creates depth, flow patterns that suggest movement, reflections that show environment, and details that ground the water in a believable landscape. These principles work whether you’re sketching in pencil, painting in watercolor, or working digitally.

Understanding River Behavior

Before drawing rivers, understand what you’re actually depicting. Rivers aren’t static shapes—they’re water responding to gravity and terrain.

What Makes Rivers Different from Other Water

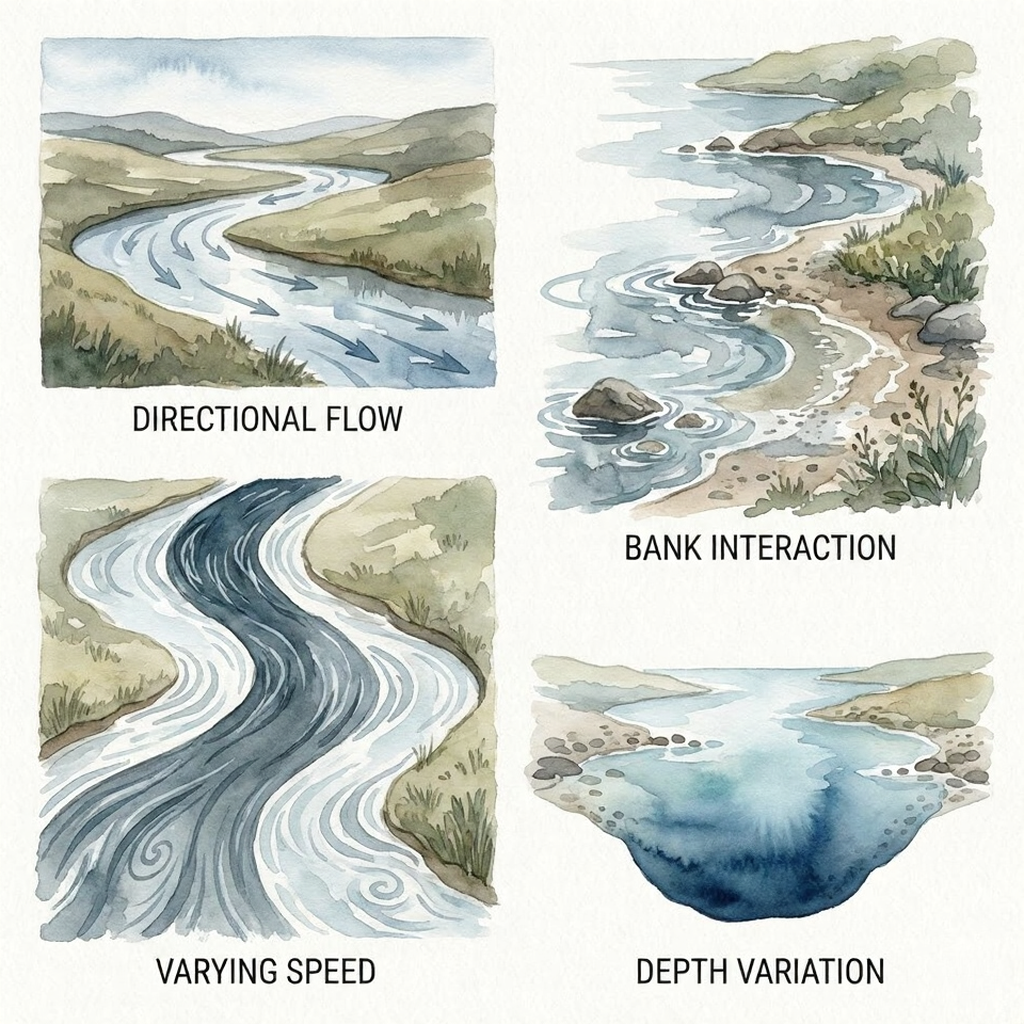

Rivers have unique characteristics that still water doesn’t share:

Directional flow: Rivers move from higher elevation to lower. This constant movement creates surface patterns, affects reflections, and determines how every element in the scene interacts with the water.

Varying speed: Water moves faster in narrow sections and the center of the channel, slower at wide sections and near banks. These speed variations create visible surface differences.

Bank interaction: The edges of a river aren’t clean lines—water meets land in complex ways, creating eddies, wash zones, and transition areas.

Depth variation: Rivers are shallow near banks and deeper in the center (usually). This depth gradient affects color, transparency, and visible bottom detail.

Understanding these behaviors helps you make intentional drawing choices. When you know why ripples cluster near rocks, you’ll draw them in the right places without guessing.

How Terrain Shapes Rivers

Rivers don’t exist in isolation—they’re shaped by everything around them:

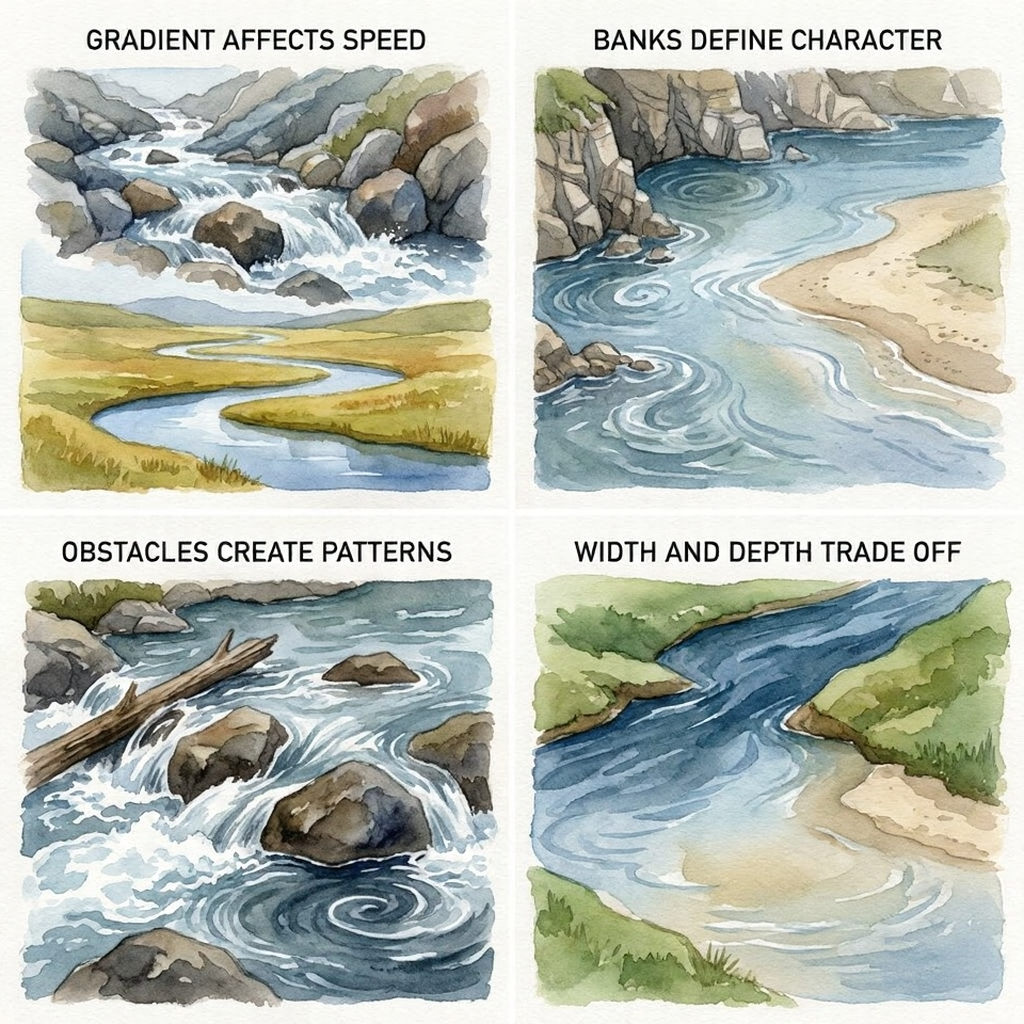

Gradient affects speed: Steep mountain streams are fast, turbulent, and full of white water. Gentle valley rivers are slow, wide, and reflective. Know your terrain before drawing.

Banks define character: Rocky banks create different water behavior than sandy beaches or vegetated edges. Hard obstacles create sharp flow changes; soft banks create gradual transitions.

Obstacles create patterns: Every rock, fallen log, or sandbar affects downstream flow. Water accelerates around obstacles, creates eddies behind them, and may form standing waves.

Width and depth trade off: Where rivers narrow, they often deepen and speed up. Where they widen, they typically shallow out and slow down.

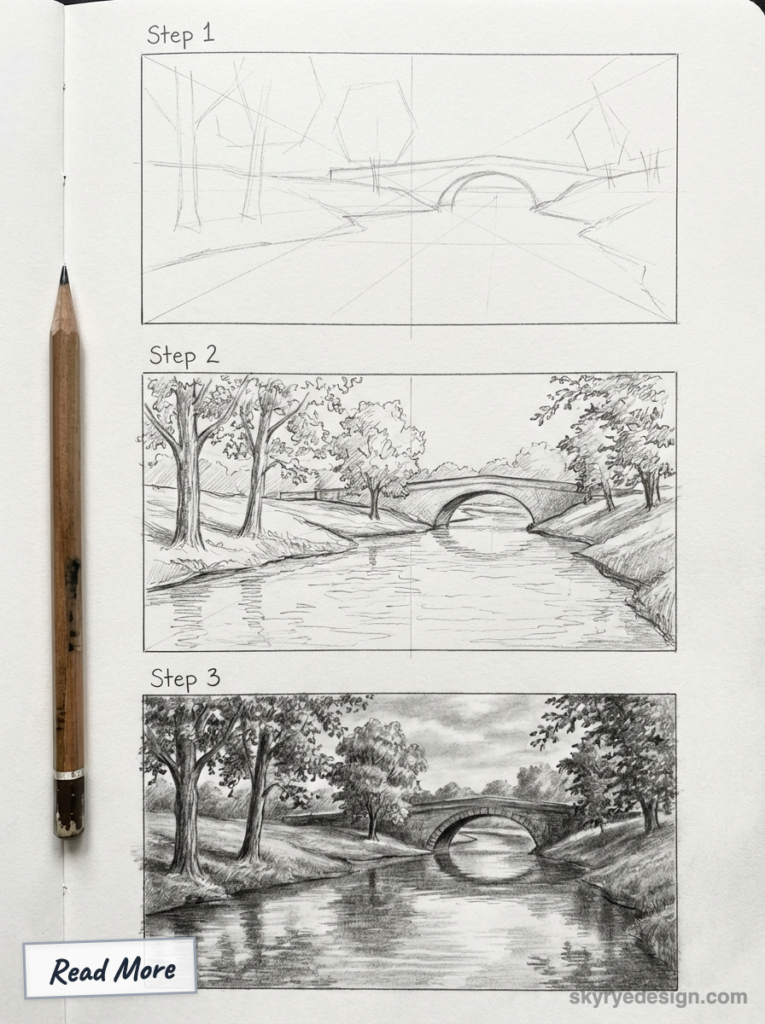

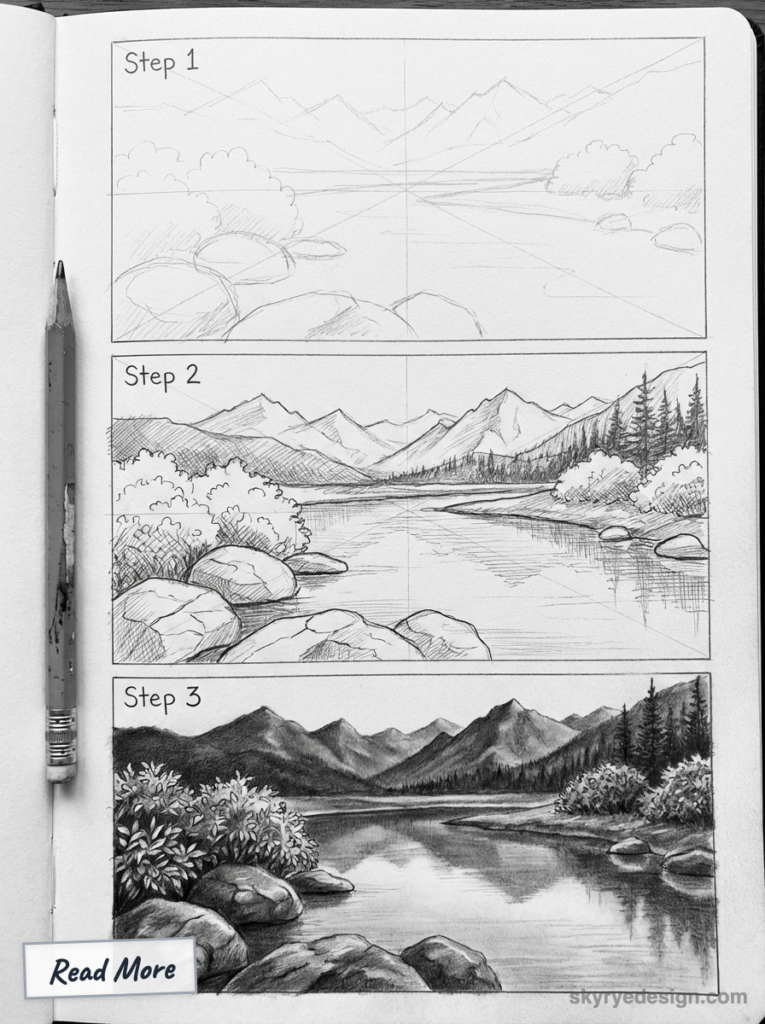

The Perspective Challenge

Rivers present a specific perspective problem: they’re horizontal surfaces receding into distance.

Convergence is critical: River banks must converge as they recede. This isn’t optional—without proper convergence, rivers look impossibly wide or completely flat.

The water surface follows terrain: The river surface isn’t perfectly flat—it follows the underlying terrain’s gentle curves. In rapids, the surface is obviously uneven; in calm water, the curvature is subtle but present.

Foreground vs. background treatment: Near water shows detail (individual ripples, visible reflections, bank texture). Distant water simplifies to value and suggestion.

Setting Up Your River Drawing

Before adding any water, establish the structural elements that will make your river believable.

Establishing the Banks

The banks come first—they define everything about your river:

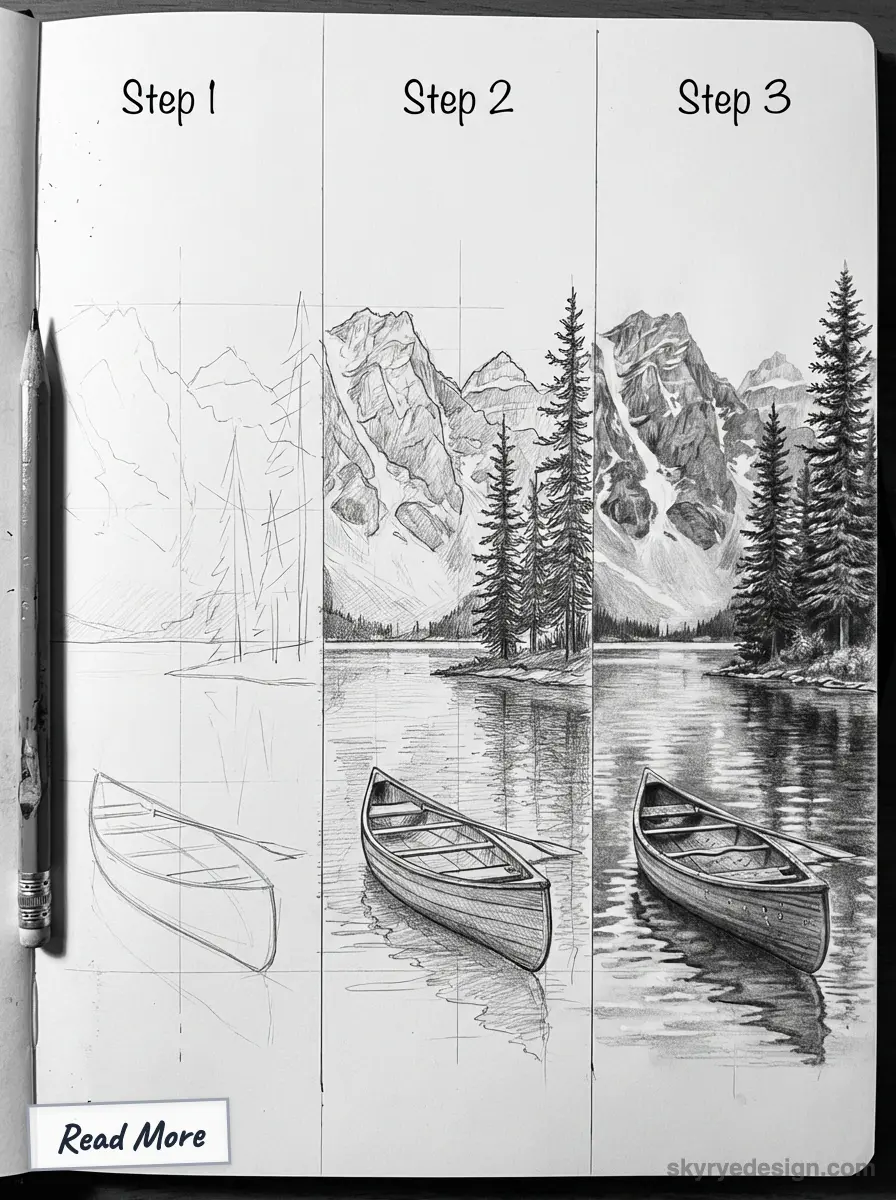

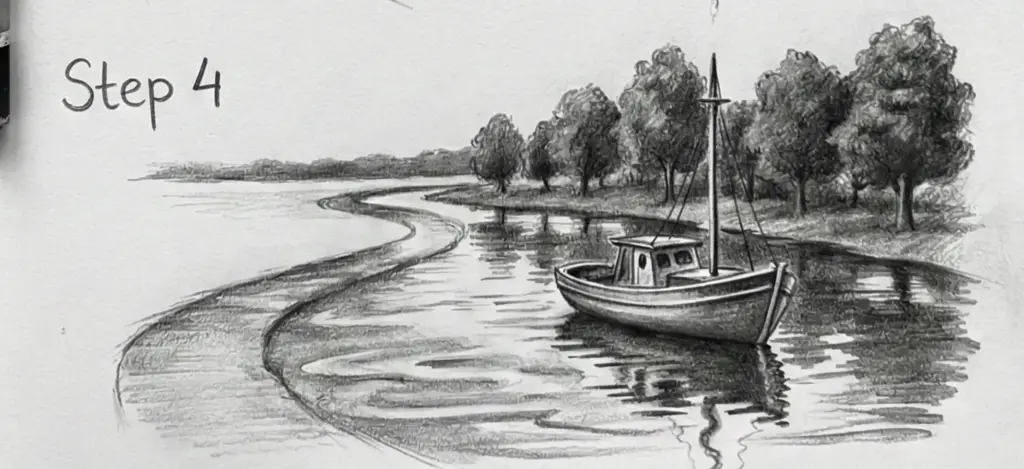

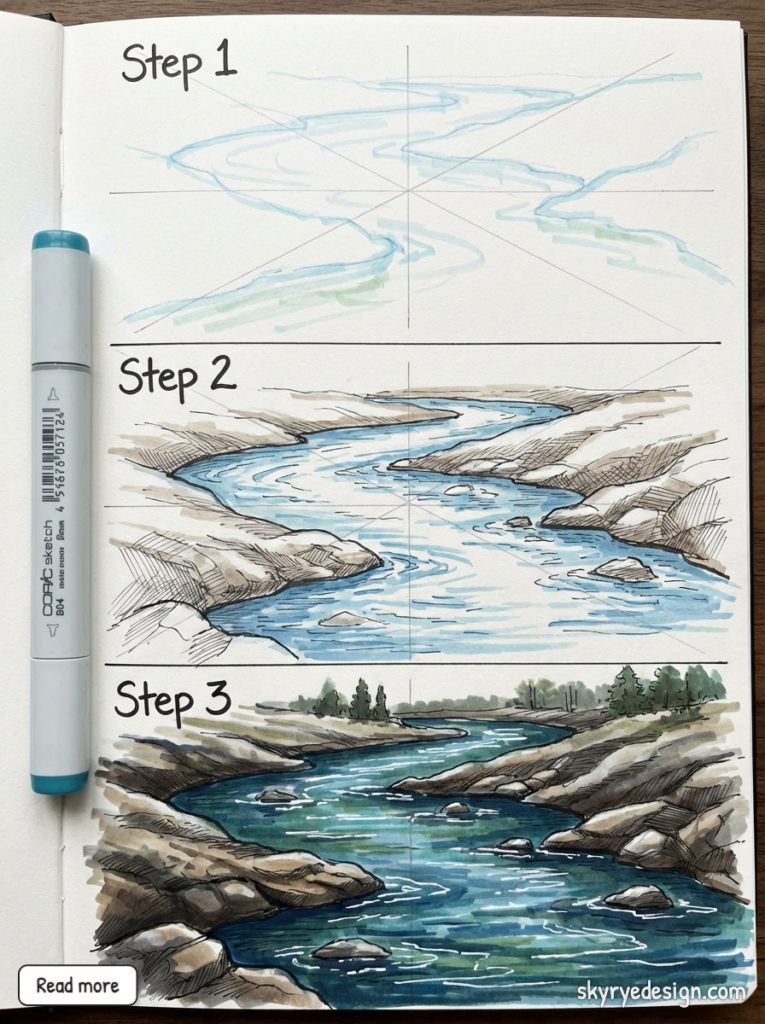

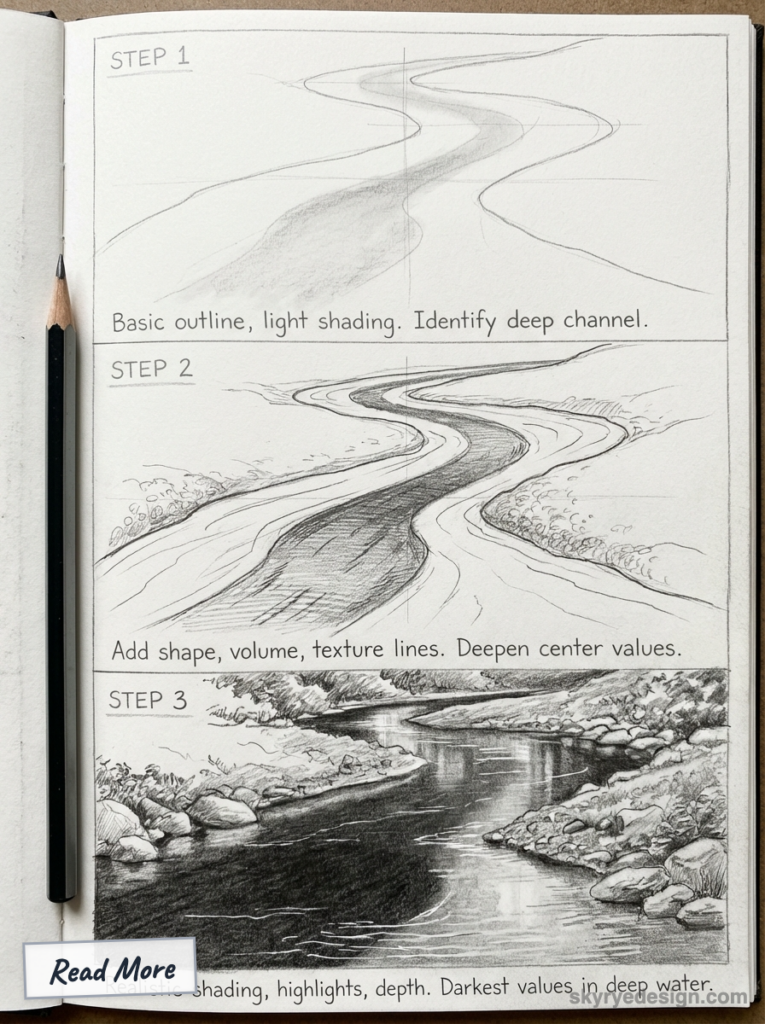

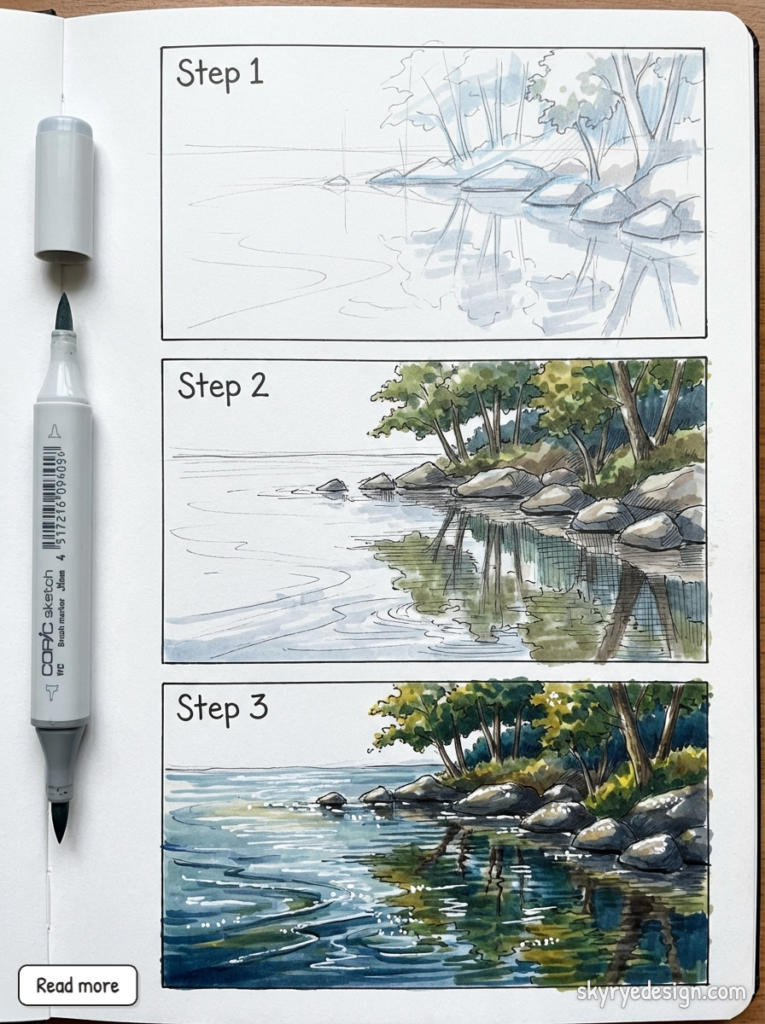

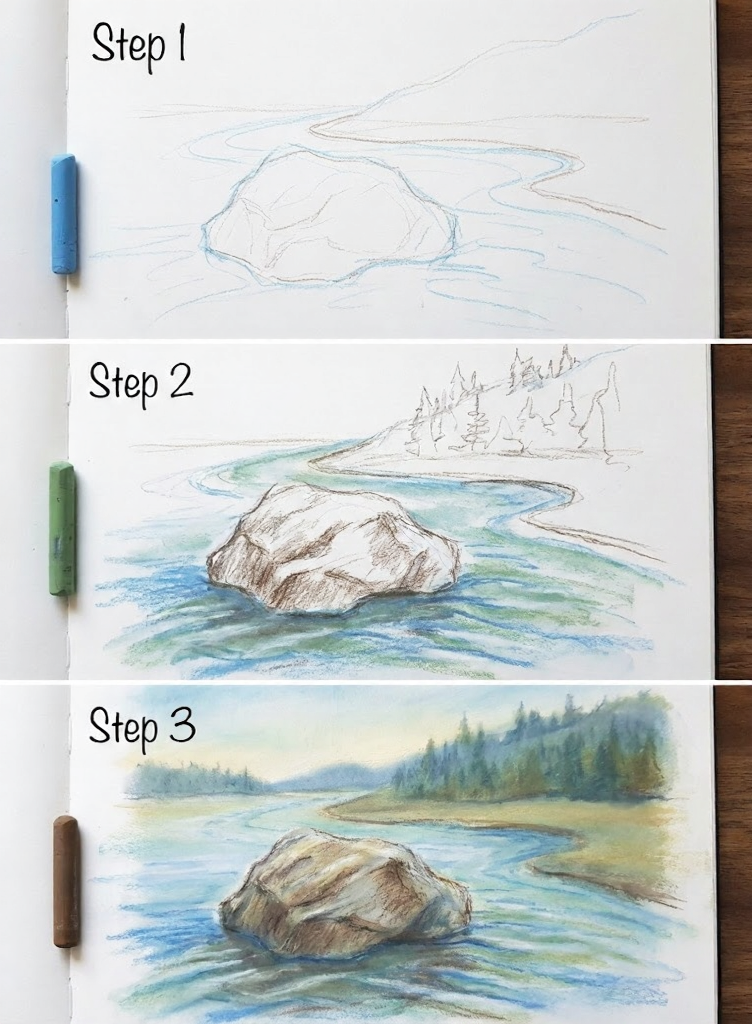

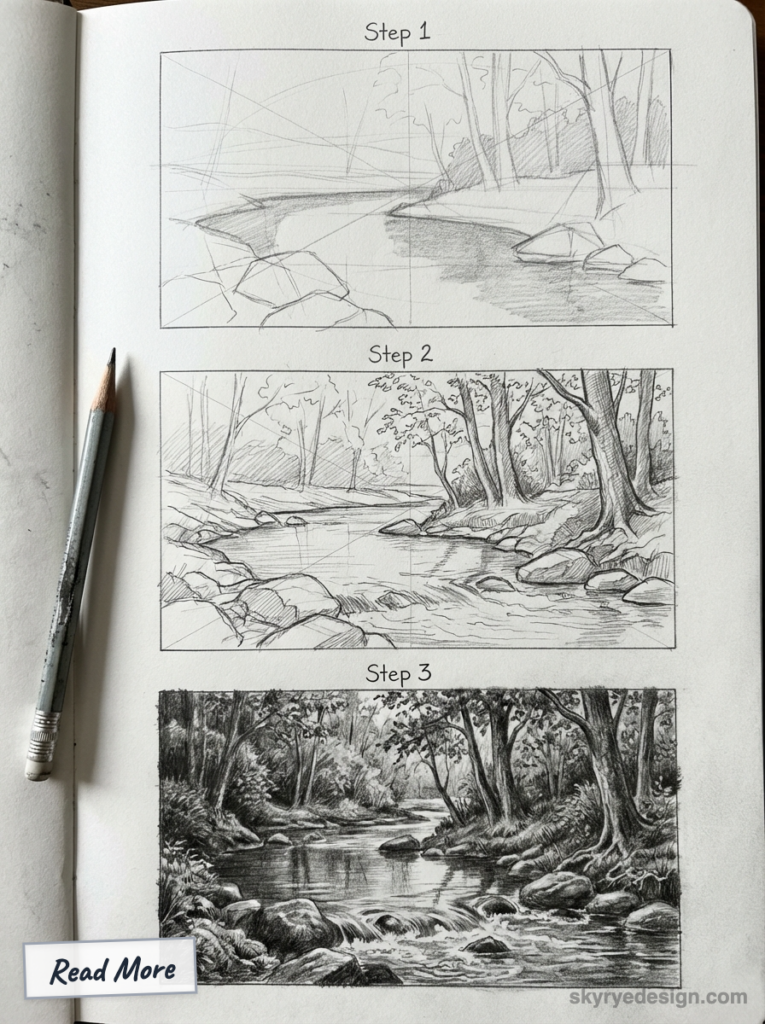

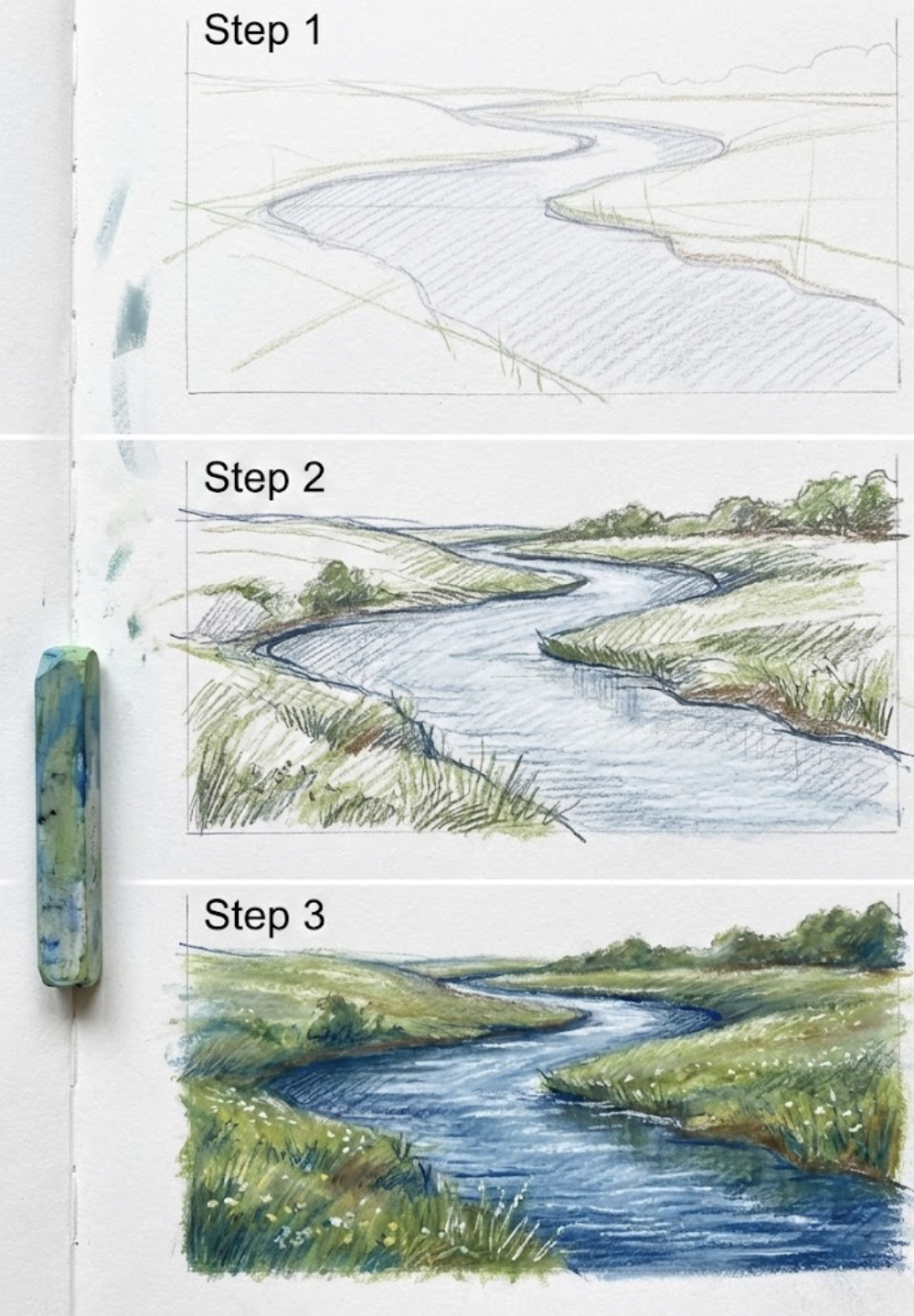

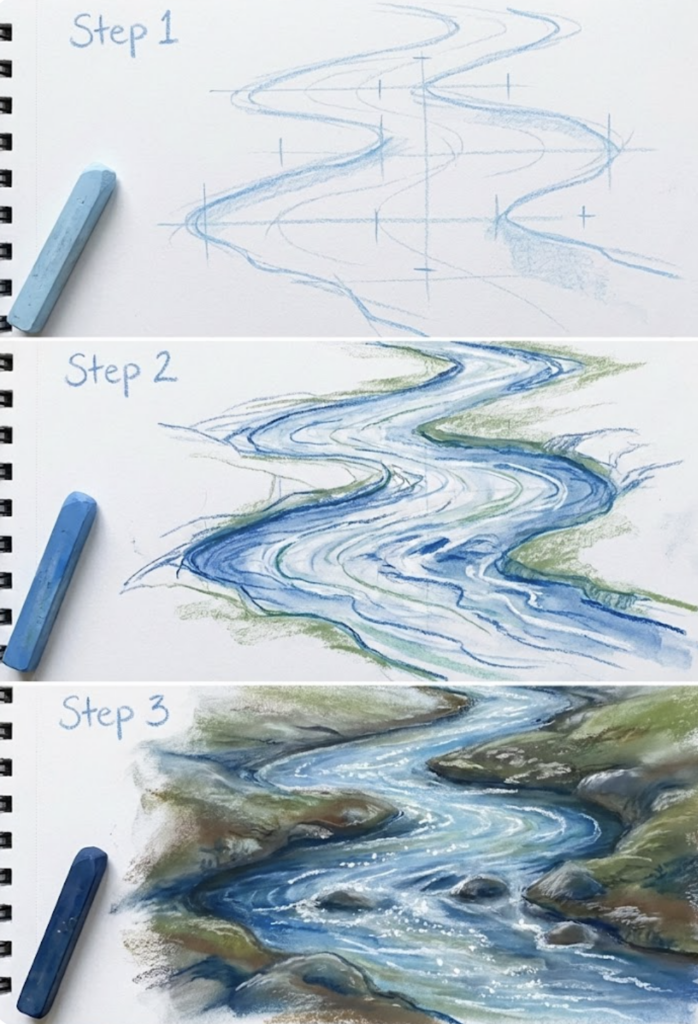

Step 1: Decide your viewpoint

Are you looking at the river from above, from bank level, or from within the water? Higher viewpoints show more water surface; lower viewpoints emphasize banks and reflections.

Step 2: Draw the near bank

Start with the bank closest to the viewer. This line can be nearly horizontal if the bank is close, or angled if it recedes.

Step 3: Draw the far bank with convergence

The far bank line should converge toward the near bank as both extend into the distance. The rate of convergence determines how far the river extends.

Step 4: Add bank character

Banks aren’t straight lines. Add curves, indentations, and jutting points. Rocks may break the bank line. Vegetation may hang over. Make banks look like places water actually meets land.

Common mistake: Drawing banks as parallel lines. This makes rivers look like roads or canals. Real river banks respond to water flow—they’re cut where water runs fast, built up where it runs slow.

Indicating Flow Direction

Before adding any water detail, establish which way the river flows:

The vanishing point method: If the river flows away from the viewer, the convergence point is where it seems to disappear. If the river flows toward the viewer, the water widens as it approaches.

The gradient method: Water flows downhill. In your composition, subtle value shifts can suggest the downstream direction—slightly lighter values toward the horizon where sky reflects more strongly.

Flow lines: Light, curving guidelines following the current direction. These aren’t visible in the final drawing but guide all your water detail placement. Draw them lightly in the direction water moves.

Creating Depth Through Values

Before adding any detail, establish your basic value structure:

Distant water is lighter: Atmospheric perspective affects rivers too. Far water approaches the value of the sky.

Deep water is darker: Where the river deepens (usually toward the center), values darken because you’re seeing less reflected light and more absorbed light.

Shallow water shows bottom: Near banks or over sandbars, the riverbed may be visible, affecting color and value.

Reflections match surroundings: Dark forest reflects as dark water; bright sky reflects as light water. Your river’s value pattern depends on what’s around it.

Drawing the Water Surface

Now add the elements that make your river look like moving water.

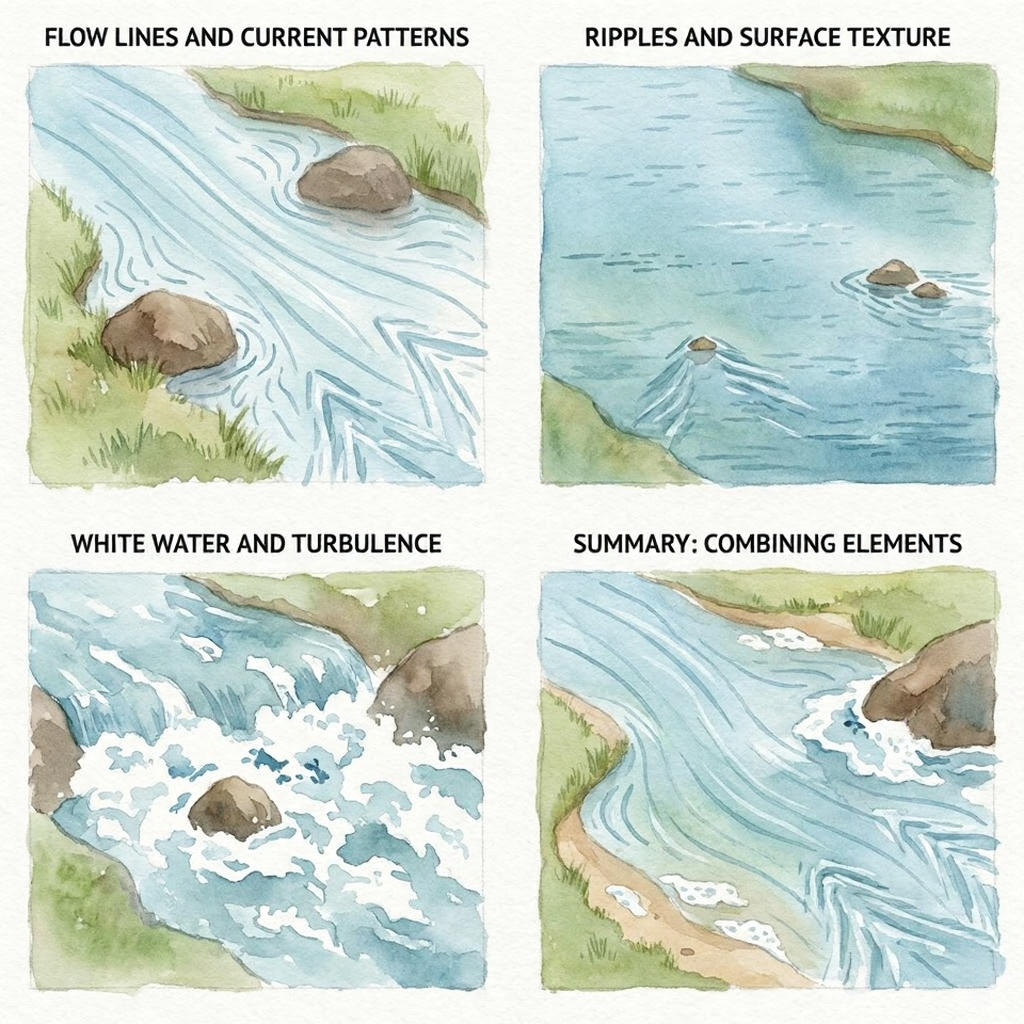

Flow Lines and Current Patterns

Flow lines are your primary tool for depicting movement:

Follow the current: All surface marks should align with water flow direction. Even subtle lines must respect the overall current.

Vary line character: Fast water gets longer, more parallel lines. Slow water gets shorter, more irregular marks. Turbulent water gets chaotic, crossing patterns.

Center vs. edge: The fastest flow (longest lines) typically runs through the center channel. Near banks, water slows and lines become shorter, more curved.

Around obstacles: When flow encounters a rock or log, lines curve around the upstream side and create V-shaped wake patterns downstream.

Drawing tip: Don’t outline every ripple. Suggest flow with selective marks—a few well-placed lines imply more than dense, uniform coverage.

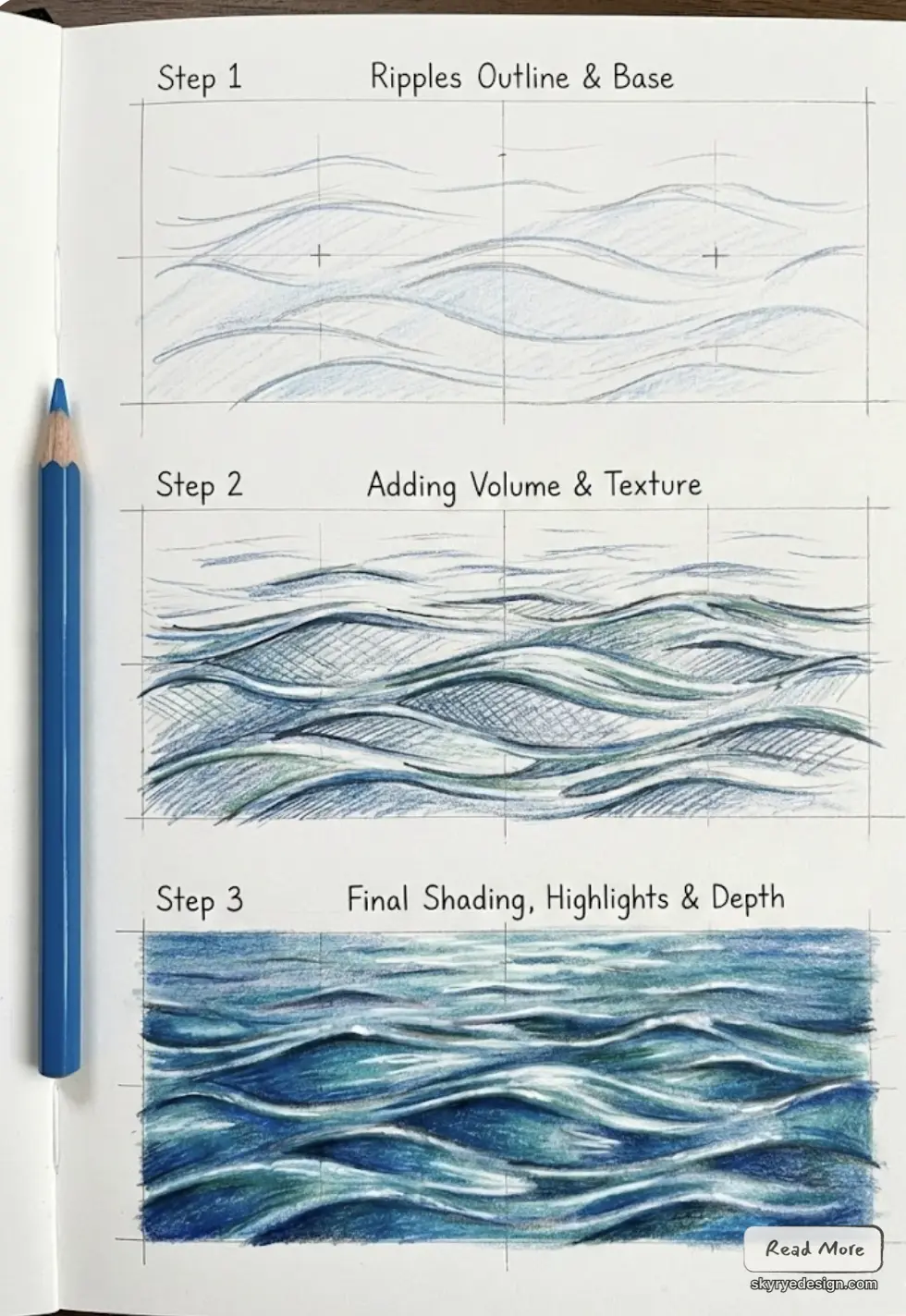

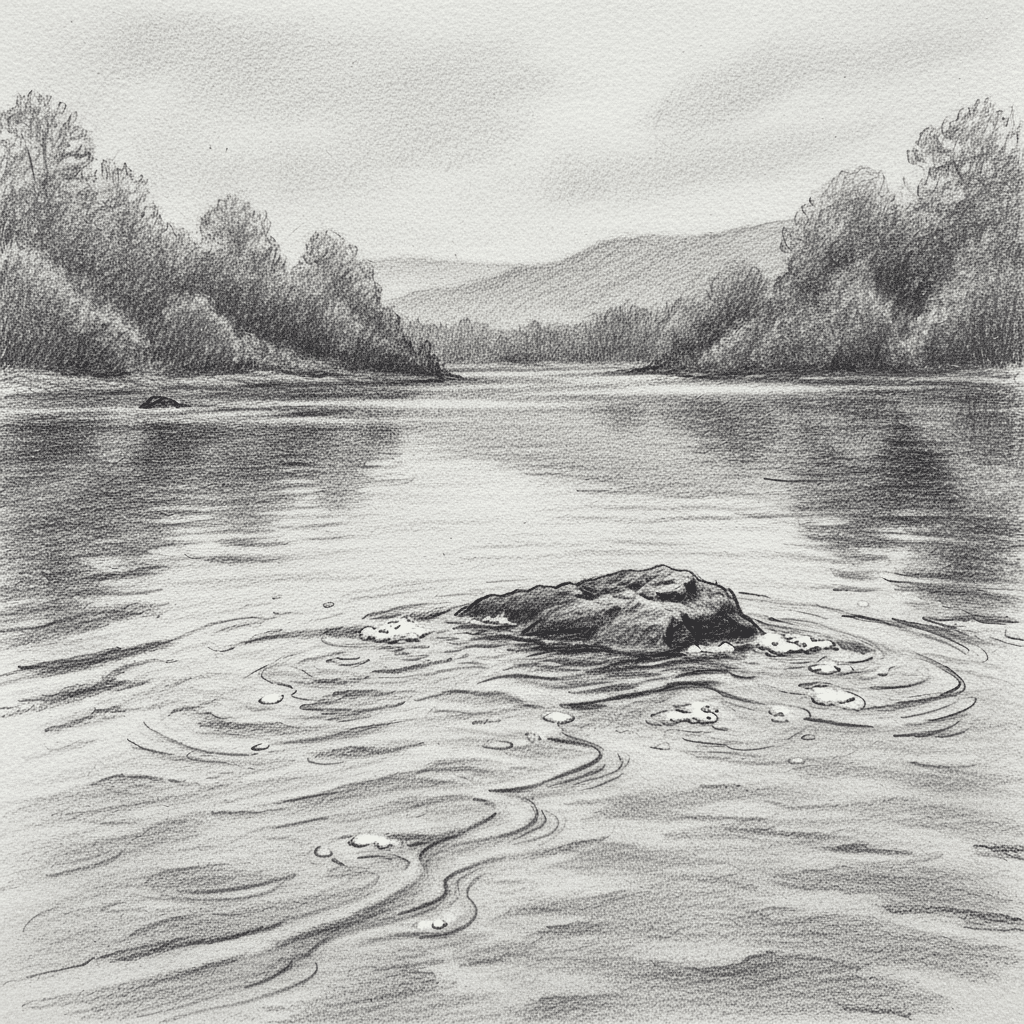

Ripples and Surface Texture

Ripples add life but require restraint:

Wind ripples: Small, irregular surface texture across the entire water. These aren’t waves—they’re subtle variations that catch light differently. Indicate with broken, horizontal-ish marks.

Current ripples: Longer, more directional marks following the flow. These form where faster water meets slower, or where shallow water runs over rough bottom.

Wake ripples: V-shaped patterns behind any object breaking the surface—rocks, sticks, boat movements. The V opens in the direction of flow.

How much is enough: Less than you think. A river with ripples everywhere looks chaotic. Most of the water surface should be relatively calm, with ripples clustered at meaningful locations—obstacles, speed changes, wind-affected areas.

White Water and Turbulence

Fast rivers and obstacles create white water:

What white water actually is: Air mixed with water. Turbulence traps air bubbles, which scatter light and appear white.

Where it forms: At drops (small waterfalls), around large obstacles, where fast water meets slow, at the base of rapids.

How to draw it: Leave paper white or use lightest values. White water shapes are irregular and chaotic—avoid geometric patterns. Add a few dark accents within the white to suggest the chaotic water movement.

Foam patterns: White foam collects in eddies and along bank edges downstream from turbulent areas. These aren’t pure white—they’re pale, irregular shapes that fade at edges.

Common mistake: Making white water too uniform or too bright across the whole area. Real white water has internal variation—some areas more aerated than others.

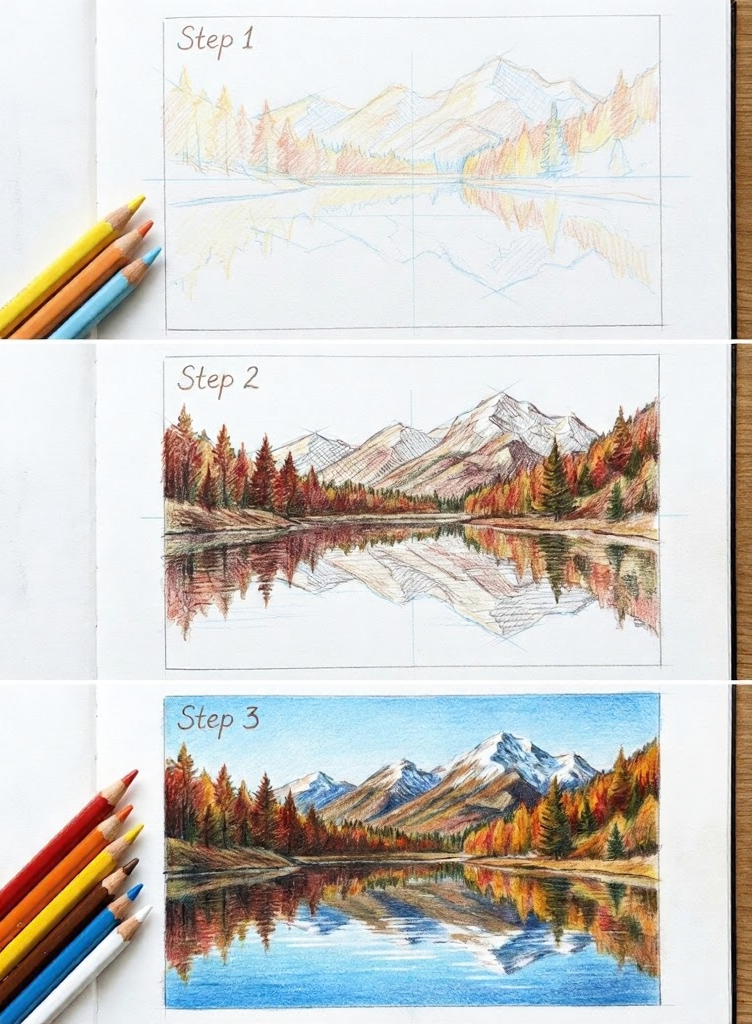

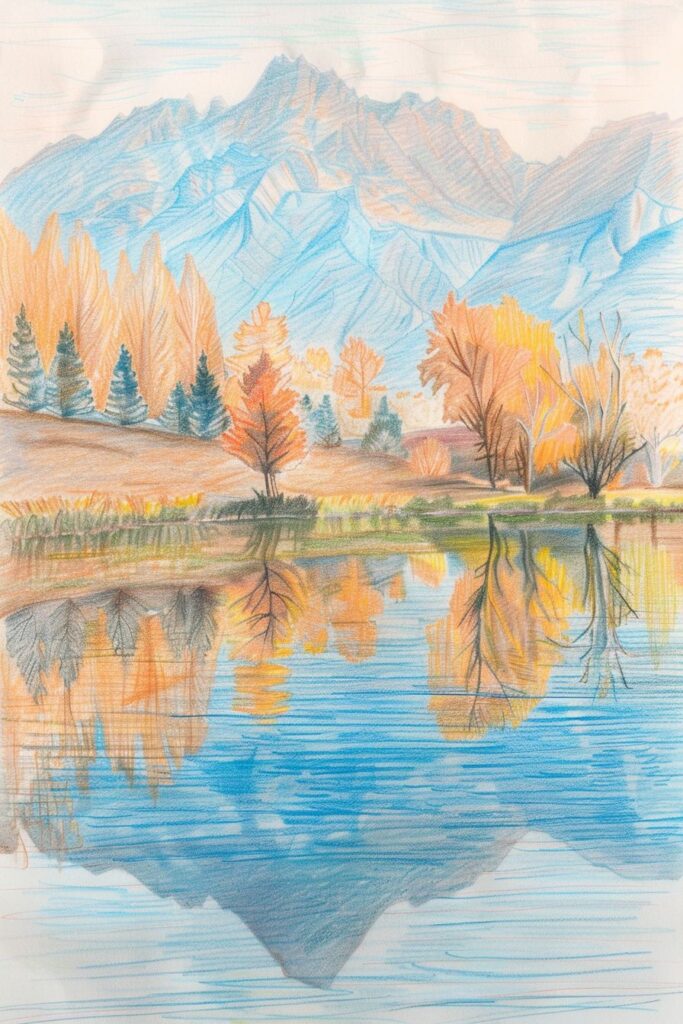

Reflections in Moving Water

Reflections make rivers look wet. But river reflections work differently than still-water reflections.

How Movement Affects Reflections

Moving water breaks up reflections:

Still water = clear reflections: A perfectly calm river mirrors its surroundings almost exactly.

Slow movement = stretched reflections: Gentle current stretches reflections vertically, making them slightly longer and softer than the objects they reflect.

Moderate movement = broken reflections: Current ripples break reflections into vertical streaks. The reflection is recognizable but fragmented.

Fast movement = no clear reflections: Turbulent water scatters light too much for coherent reflections. You’ll see general color influence but no mirror images.

Drawing River Reflections

For typical slow-to-moderate rivers:

Reflections are vertical: Objects reflect directly downward from the waterline—a tree on the bank reflects straight down into the water, not at an angle.

Reflections stretch downward: The base of an object appears at the waterline; the top of the reflection extends away from you into the river.

Break them up: Use horizontal marks to show where current interrupts the reflection. These breaks should follow your flow direction.

Value shifts: Reflections are typically slightly darker and less saturated than the objects they reflect. Darken and dull your reflection colors/values.

Edge treatment: Where reflections meet the actual bank, the transition should be soft and somewhat ambiguous—water and reflection blend rather than having a hard edge.

Selective Reflection

You don’t need to reflect everything:

Prioritize large, dark elements: Trees, hills, and buildings create the most noticeable reflections.

Simplify: A forest’s reflection becomes a general dark shape, not individual tree reflections.

Sky reflection: Where no objects reflect, the water reflects sky. This is typically the lightest area of your river.

Adding Environmental Context

Rivers exist within landscapes. The surrounding elements complete the scene and ground your water in reality.

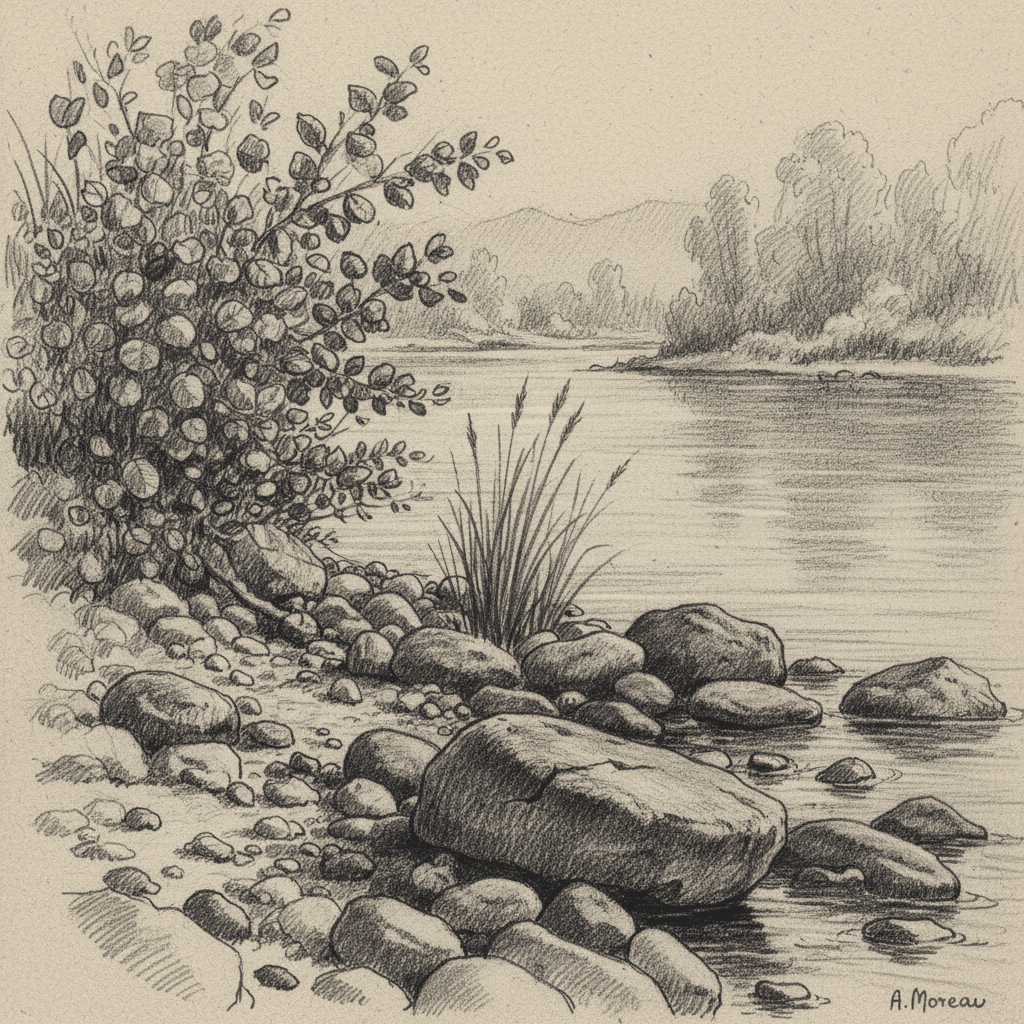

Banks and Edges

The waterline transition is crucial:

The wet zone: Where water meets land, there’s typically a darker, wet area just above the waterline. Rocks are wet; sand is damp; vegetation is splashed.

Undercut banks: Fast water often cuts underneath banks, creating shadows and overhangs. This adds depth and interest.

Gradual vs. steep: Sandy beaches slope gently into water; rocky banks drop steeply. Match your bank treatment to your terrain type.

Vegetation at edges: Reeds, grasses, and overhanging branches populate riverbanks. These elements overlap the water, creating interesting intersections.

Rocks and Obstacles

Rocks make rivers visually interesting:

Exposed rocks: Rocks above water are lightest on top (sun-hit), with wet zones at waterline showing darker values.

Partially submerged rocks: The waterline creates a distinct edge. Below water, rock color shifts toward the water’s color and edges soften.

Underwater rocks: Visible through shallow water as darker shapes with soft edges, affected by surface ripples and refraction.

Wake patterns: Every rock creates a wake pattern downstream. The faster the water, the more pronounced the wake.

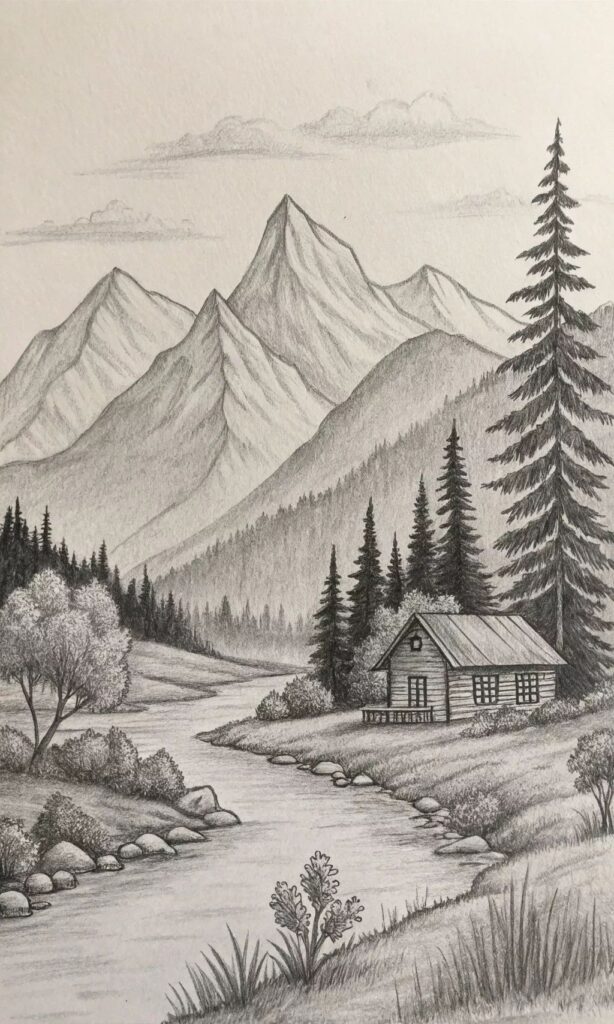

Surrounding Landscape

Context determines river character:

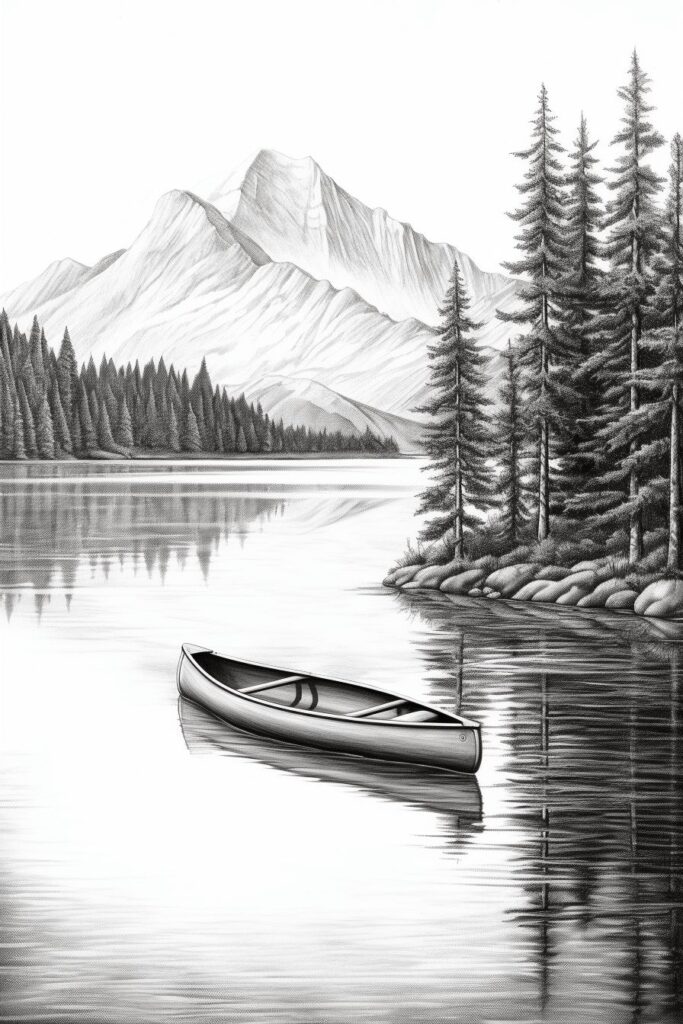

Mountain rivers: Rocky banks, steep terrain visible, possibly snow, evergreen trees. Water is typically clearer and more turbulent.

Forest rivers: Tree canopy, dappled light, organic bank shapes, fallen logs. Water may be darker from tannins, calmer flow.

Meadow rivers: Open sky, grass banks, possibly meandering path, wide and slow. Strong sky reflections, visible bottom in shallows.

Each environment changes your drawing approach. A mountain stream and a lowland river require completely different handling of water, reflections, and surroundings.

Light and Atmosphere

Light transforms river drawings from technical exercises into evocative scenes.

Time of Day Effects

Light direction changes everything:

Midday: Sun high, reflections brightest, strong contrast, flat lighting on water surface.

Morning/evening: Low sun creates long shadows, warm colors, potential for dramatic light paths across water.

Overcast: Diffuse light, less contrast, softer reflections, cooler colors.

Backlighting: Sun behind the scene creates silhouettes and can make water surface glow where it catches direct light.

Shadows on Water

Rivers receive shadows from surrounding elements:

Tree shadows: Fall across the water surface, following the flow as curved or broken shapes.

Bank shadows: One side may be in shadow depending on sun position, creating clear value division.

Cloud shadows: Large soft shapes moving across the river, creating interesting patterns.

Shadow treatment: Shadows on water aren’t solid—they’re affected by surface movement and reflection mixing. Keep shadow edges soft on moving water.

Atmospheric Perspective

Distance affects river appearance:

Distant water loses contrast: Far sections of river approach a uniform middle value.

Colors cool with distance: Near water shows local colors; far water shifts toward atmospheric blue-gray.

Detail disappears: Distant ripples, reflections, and bank detail simplify to suggestion.

Using atmosphere: Strong atmospheric perspective creates depth even in flat terrain. Push your distant river values toward sky values.

Common Problems and Solutions

Problem: River Looks Flat

Symptoms: No sense of depth; river appears as a colored shape rather than a receding surface.

Solutions:

- Check bank convergence—are lines converging enough?

- Add atmospheric perspective—lighten distant water

- Vary your detail density—more in foreground, less in background

- Ensure flow lines recede with the perspective

Problem: Water Looks Solid

Symptoms: River looks like a blue surface rather than liquid.

Solutions:

- Add reflection elements—even broken reflections suggest surface

- Include transparency cues—visible bottom in shallows

- Vary surface treatment—not all areas should have the same texture

- Check your values—water has internal value variation

Problem: Flow Direction Unclear

Symptoms: Viewer can’t tell which way the river moves.

Solutions:

- Check flow line direction consistency

- Add wake patterns behind obstacles (V-shape points downstream)

- Use ripple patterns that follow current

- If including white water, place it logically (downstream from obstacles)

Problem: Reflections Look Wrong

Symptoms: Reflections seem disconnected from their sources or at wrong angles.

Solutions:

- Darken and desaturate reflected values

- Reflections go straight down, not at angles

- Match reflection length to object height above waterline

- Break reflections with horizontal current marks

Practice Exercises

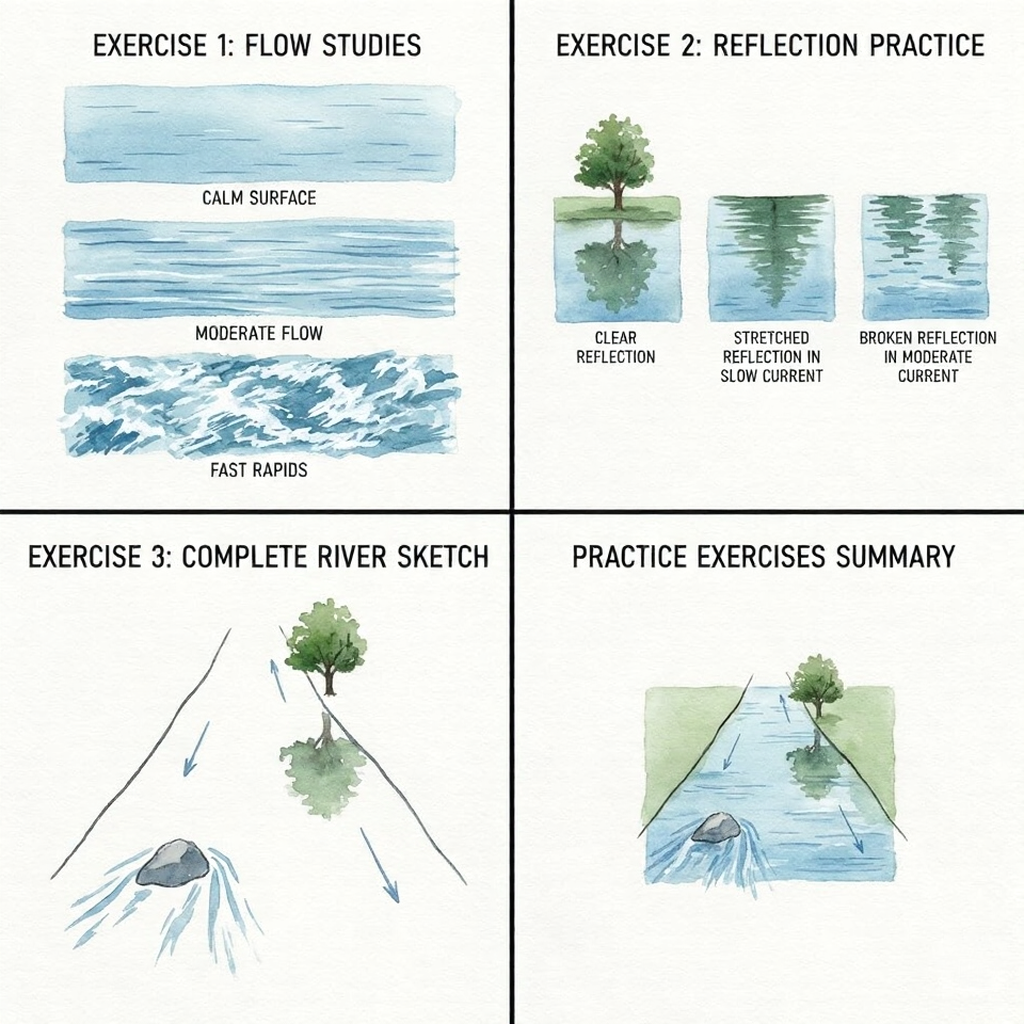

Exercise 1: Flow Studies

Draw just the water surface (no banks, no environment) showing different flow speeds: calm, moderate current, fast rapids. Focus only on how surface marks suggest movement speed.

Exercise 2: Reflection Practice

Set up a simple scene: one tree reflected in water. Draw it three ways: in still water (clear reflection), slow current (stretched reflection), and moderate current (broken reflection).

Exercise 3: Complete River Sketch

Draw a 15-minute river sketch focusing on: bank convergence, basic flow direction, one reflection area, one rock with wake pattern. Don’t render—just establish the structural elements.

FAQ

How do I make my river look like it’s flowing and not just sitting there?

Flow direction must be consistent across all water marks. Every ripple, reflection break, and surface line should follow the same current direction. Add wake patterns behind obstacles (V-shapes pointing downstream). Place white water and turbulence at logical locations where fast water meets obstacles.

What colors should I use for river water?

Rivers aren’t one color. They reflect sky (often blue-gray), reflect surroundings (greens from trees, earth tones from banks), show depth (darker in deep areas, lighter in shallows), and may have local color from sediment (browns, greens, even reds). Build river color from these components rather than reaching for “water blue.”

How do I draw a river from different angles?

High viewpoint: more water surface visible, banks frame the view, reflections compressed. Low viewpoint: banks dominate, less water surface visible, reflections elongated. Looking upstream: river narrows toward horizon. Looking downstream: river widens toward viewer. Each viewpoint requires adjusting your perspective approach.

How do I show shallow vs. deep water?

Shallow water shows the bottom—rocks, sand, vegetation visible through the surface. Colors shift toward the bottom color. Deep water hides the bottom—values darken as light is absorbed, color shifts toward water color (often darker blue-green), less transparency.

Should I draw every ripple I see?

No. Selective indication is more effective than comprehensive coverage. Cluster ripples at meaningful locations: obstacles, speed changes, wind-affected areas. Leave large areas relatively calm with just flow direction suggested. The eye fills in what you imply.

Conclusion

Drawing rivers that look like actual flowing water requires understanding what rivers do, not just what they look like. Rivers flow, interact with terrain, reflect their surroundings, and constantly respond to obstacles and gradient. Your drawing needs to show these behaviors, not just fill in a river-shaped area with blue.

The fundamentals are straightforward: banks that converge properly, flow lines that follow current direction, reflections that respond to surface movement, and environmental details that ground the water in a believable landscape. Master these elements and you can draw any river—mountain torrents, lazy meadow streams, or wide delta channels.

This week: Draw three simple river studies focusing only on bank perspective and flow direction. No rendering, no detail—just the structural lines that establish where the river goes and how it moves.

Next month: Add one complexity per study: reflections, then rocks, then surrounding vegetation. Build your river drawings systematically rather than trying everything at once.

Ongoing: Visit actual rivers. Watch how water moves around obstacles, how light plays on surfaces at different times, how banks actually meet water. Photography helps, but there’s no substitute for sitting by a river and watching it flow.

Rivers are challenging because they combine multiple drawing problems: water, perspective, reflection, and landscape. But they’re also rewarding—a well-drawn river brings an entire scene to life, suggesting movement and change even in a static image.

Start simple. One river, clear perspective, consistent flow direction. Everything else builds from that foundation.

- 4.7Kshares

- Facebook0

- Pinterest4.7K

- Twitter0

- Reddit0